DISCLAIMER

This is a work of fiction. While it incorporates historical events, all characters, conversations, and supernatural elements are fictional. Any resemblance to real persons beyond general historical context is coincidental. Historical liberties have been taken for narrative purposes. Future chapters are speculative fiction only. All rights reserved ManicMalta.com. This book cannot be reproduced in part or in full, copied or printed. .

THE PILOT ARRIVES – APRIL 1942

The Spitfire landed hard, bouncing once on Luqa’s dusty runway before settling with a screech of rubber. Its propeller spun to stillness as the engines cut, the sudden silence almost shocking after the constant roar. It was April 1942, and Malta was dying.

I felt him before I saw him. Not his face or form, but the rhythm of his blood. A strange, familiar pulse that echoed through metal, through stone, through time itself.

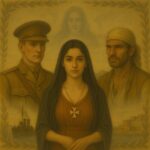

Denis Barnham, age twenty-two, climbed stiffly from the cockpit. He was lean and sunburned, with hands that bore calluses in places different from most men who worked these islands. Pilot’s hands. Artist’s hands. Hands that descended from a dock worker who once threw pebbles at gulls and apologized when they scattered.

He didn’t speak as the ground crew swarmed his aircraft, checking for damage, refueling for tomorrow’s desperate sorties. Instead, he found a wooden crate, sat down, and pulled a sketchbook from his flight jacket. With quick strokes, he began drawing the airfield—the burned-out hangars, the craters like pockmarks across the tarmac, the thin smoke rising from Valletta in the distance.

I had never believed in blood calling to blood, in the pull of ancestry across years and miles. But watching him—this English pilot with Maltese eyes—I wondered. He was the son of Maria and Manwel, though neither had lived to tell him so. One died on Valletta’s stones. The other faded slowly in Surrey, her heart still beating but her spirit long returned to these shores.

And now their son had come home, wearing a uniform so different from the one that had taken his father’s life.

Squadron Leader Woodhall approached, clapping Denis on the shoulder. “Welcome to Malta, Barnham. Hell of a place these days.”

Denis nodded without looking up from his sketch. “How many aircraft are operational?”

“Three. Maybe four by morning, if the engineers work miracles. Which they do, daily.”

“And pilots?”

“Fewer than planes, now.”

Denis closed his sketchbook. His eyes scanned the horizon, where the setting sun painted the limestone buildings in shades of blood and fire. “I’ll be ready at dawn.”

There was no recognition in his eyes, no sense that he had come home rather than to some distant, embattled outpost of empire. But I felt it—the resonance between him and the island. Like two tuning forks struck in sequence, vibrating at frequencies only I could detect.

He had arrived with the last wave of reinforcements, twenty-seven Spitfires flown off the deck of USS Wasp. These aircraft represented Malta’s hope against the relentless Axis assault—German Stukas, Italian Macchis, and bombers that turned the sky black with their numbers.

I had witnessed centuries of siege. Knights and Ottomans. French and Maltese. But never had death come so completely from above. Never had my people been so hunted from the sky.

And so Malta burned. And bled. And endured.

Lightning strikes twice Son returns to father's home Unknowing, unknown

BLOOD FROM THE SKY – APRIL-MAY 1942

Dawn came with the air raid sirens.

Denis was already at his aircraft, checking controls, running gloved fingers over the Spitfire’s elegant, lethal lines. At twenty-two, he was younger than most of the squadron’s pilots, but war had made everyone ageless—boys of nineteen with old men’s eyes, veterans of thirty who moved with the caution of the ancient.

“Bandits approaching from the north,” the controller’s voice crackled over the radio. “Many bandits. Angels fifteen. Looks like a major raid.”

I felt the approaching aircraft before human instruments could detect them. The hum of their engines, the vibration of their metal skins, the magnetic disturbance they created as they pushed through the Mediterranean sky. Sixty-four bombers. Twenty-seven fighters as escort.

They carried death in steel casings, in bullets tipped with destruction, in the cold intention of their pilots.

Denis pulled on his flying helmet, face tight with concentration. No fear showed, just the calm calculation of a man who had already accepted that each dawn might be his last.

He was the third Spitfire to take off, climbing steeply into the blinding sun. The formation was pitifully small—just three aircraft to face an armada.

“Half of us climb higher,” came the squadron leader’s voice. “Barnham, you’re with me. We’ll hit them from above while Mason draws their escort.”

An impossible strategy. A desperate gamble. But these men no longer measured success by enemy aircraft destroyed. Success meant one more day of Malta breathing.

The air battle erupted with a suddenness that never failed to shock. One moment, the sky was empty except for distant specs. The next, it was filled with twisting metal, tracer fire, black smoke, and diving aircraft.

Denis rolled his Spitfire inverted, then pulled through into a dive that took him straight into the bomber formation. His guns chattered briefly—four seconds of fire that sent a Ju 88 trailing smoke, losing altitude as its pilot fought for control.

An Italian Macchi appeared in his mirror, closing fast. Denis pulled harder, his aircraft groaning under the strain, but the enemy fighter stayed with him, its guns winking.

I felt the bullets—tiny metal darts vibrating with deadly intent. One struck Denis’s airframe, then another. The third would have found his fuel tank.

I had never tried to influence so small a thing moving so quickly. But I reached out, wrapped my consciousness around that bullet as it left the Macchi’s wing, and tipped it—just slightly. Just enough.

The round struck harmlessly, deflected by a fraction of a degree that made all the difference between life and oblivion.

Denis wrenched his aircraft around, reversing the pursuit so suddenly that the Italian pilot overshot. A brief burst from the Spitfire’s eight guns, and the Macchi tumbled from the sky, trailing fire.

But the bombers had broken through. They flew on toward Valletta, toward the Grand Harbour, toward the civilian districts that had already endured so much.

I felt their bomb bays open. The mechanical release. The terrible pause as gravity claimed its offerings.

Then the first explosions. Like giant footfalls of some angry god. Like thunder trapped inside the earth. And the limestone—my limestone—cracked and shattered, carrying away lives that had taken root among my stones.

When Denis landed two hours later, his Spitfire had four bullet holes in its fuselage and barely enough fuel to reach the runway. As ground crew swarmed the aircraft, he sat motionless in the cockpit, eyes closed, hands still gripping the control column.

Finally, he climbed down, removed his helmet, and walked to the edge of the airfield. From there, he could see the smoke rising from multiple points across the island.

Squadron Leader Woodhall joined him, offering a cigarette. “Two confirmed kills. Not bad for your first day.”

Denis shook his head. “Not enough. Never enough.”

Bullets like raindrops Steel birds circle, hunting prey Island crouches low

THE PIERCED DOME – APRIL 9, 1942

April 9th had dawned clear and bright, with a breeze from the northwest that promised a few hours’ respite from the usual choking dust. Inside the Mosta Rotunda, worshippers gathered for morning Mass—some three hundred souls seeking comfort in ritual and faith while war raged outside.

The massive dome above them—the third-largest unsupported dome in Europe—had stood for over a century, its golden limestone catching the morning sun through tall windows. The priest’s voice carried clearly in the perfect acoustics, speaking ancient words that had survived countless wars before this one.

I felt the approaching bombers before the air raid sirens sounded. A formation of three, flying low, their bomb bays already open. But something was different this time—they were not heading for Valletta or the harbor. Their flight path would take them directly over Mosta.

Inside the church, the faithful continued their prayers, trusting in the thick walls that had sheltered generations. Few moved when the sirens finally wailed—they had learned that constant evacuation made normal life impossible. Better to place faith in God’s protection than to live in perpetual fear.

The lead bomber released its payload—a stick of bombs that fell away from its metal belly like terrible fruit. Among them, a single 500-kilogram explosive, its fins catching the air as it plummeted toward the great dome of Mosta.

I felt the bomb as intimately as if it were an extension of myself. The metal casing. The fuse mechanism. The detonator with its electrical circuit designed to close on impact.

As it fell, I reached inside it—not with hands, for I have none, but with the electromagnetic force that has become my tool, my voice, my intervention in the physical world.

I found the fuse. Wrapped my consciousness around it. And as the bomb crashed through the dome’s ceiling—as stone fragments rained down upon the stunned congregation—I held that fuse. Slowed its action. Interrupted the circuit that would transform metal into obliteration.

The massive bomb punched through the dome’s ceiling with a sound like thunder, sending chunks of masonry tumbling to the floor. It hit the marble tiles and bounced, sliding to a stop near the altar.

But it did not explode.

For several heartbeats, silence reigned absolute. Then a child cried out, and the spell broke. People rushed for the exits, stumbling over pews, calling for loved ones. The priest stood frozen by the altar, staring at the deadly cylinder that had come to rest just meters away.

Outside, chaos erupted as people poured from the church, many falling to their knees in prayer once they reached safety. Inside, dust swirled in the sunbeams that now streamed through the jagged hole in the dome.

And still, the bomb did not explode.

Hours later, Royal Engineers arrived to defuse and remove it. They approached with the caution of men who had seen too many comrades die from booby traps and delayed-action fuses. But their instruments detected no electrical activity from the device.

“It’s a dud,” the lieutenant finally announced, his voice echoing in the now-empty church. “One in a thousand. Someone up there must like you lot.”

By evening, the story had spread across Malta. The bomb that fell through the dome during Mass but failed to explode. Divine intervention, the people said. A miracle. Proof that God had not abandoned them despite the daily harvest of death from the skies.

I felt no joy. Only a hollow tremor like distant thunder. They wept for deliverance. I sat inside the casing. I had made no miracle. Only silence.

And I wondered—was this what I was becoming? Not just a watcher, not just a recorder, but a force? A will acting upon the world rather than merely observing it?

Two days later, Denis flew over Mosta. From the air, the hole in the great dome was clearly visible, a dark puncture in the golden stone like a missing tooth. He banked his Spitfire, circling once before continuing his patrol.

That night, he sketched the dome from memory—broken but standing. He titled the drawing simply: “Survival.”

I felt the resonance of his pencil on paper, the subtle magnetism of graphite tracing stone. He drew what others would miss—not just the damage, but the defiance in that broken dome still standing. His artist’s eye saw what his conscious mind could not: the reflection of his own survival against impossible odds.

Faith tested by fire Stone yields, but does not shatter Dome stands, saved by steel

THE PAINTER OF RUIN – MAY-JUNE 1942

June found Denis still flying, still surviving, when so many others had fallen. Six confirmed kills, one shared. Enough to make him an ace, though he never used the term. His sketchbook had filled with images of war—damaged Spitfires, burning harbors, the weary faces of Maltese civilians in shelter doorways.

The ground crew had painted six small crosses near his cockpit—kills that Denis never acknowledged. For him, success was measured not in enemy aircraft destroyed, but in bombs prevented from reaching their targets. In one more day that Malta continued to breathe, to endure, to defy.

I watched him through metal—through the rivets of his aircraft, through the pencil in his hand, through the rare coins he sometimes carried as tokens. He had become familiar to me in ways I could not fully comprehend. This son of my soil who did not know his own heritage.

On June 10th, he flew three sorties in a single day—an exhausting schedule made necessary by the dwindling number of pilots. The last was at dusk, intercepting a formation of Italian bombers attempting to mine the harbor under cover of fading light.

His Spitfire, patched and repatched, struggled to climb. The engine coughed at high altitude, starved for the oxygen that Malta’s overtaxed mechanics could no longer perfectly calibrate. But still he flew, pushing the aircraft beyond its limits, beyond safety.

He shot down a Macchi that day—his seventh victory. The Italian pilot bailed out over water, his parachute blossoming white against the darkening sky. Denis circled once, noting the position for air-sea rescue, then turned back toward the bombers.

But his ammunition was spent, his fuel critical. All he could do was shadow them, hoping his presence might disrupt their careful formation, spoil their aim as they dropped their deadly cargo.

I felt his frustration. His rage. His helplessness as bombs fell despite his best efforts.

And beneath it all, something else. A deep, inexplicable connection to this place he was defending. As if somewhere in his blood, in the marrow of his bones, he knew he was protecting more than just a strategic island. He was protecting home.

When he landed at Luqa, the night was fully dark. No lights guided him—blackout conditions made the runway a barely visible strip in the gloom. He brought the Spitfire down by instinct more than sight, the wheels chirping as they touched cracked concrete.

Too tired even for food, he made his way to his quarters—a small room in what had once been a school, now repurposed as officers’ accommodations. There, by the light of a single candle, he opened his sketchbook once more.

This time, he drew a single Spitfire silhouetted against clouds, flying above the distinctive profile of Mellieħa Ridge. The aircraft was small against the vast sky, seemingly fragile, yet determined. Like Malta itself.

I felt the importance of his art even then. Each stroke on paper recording moments that might otherwise be lost to time, preserving what the human eye might miss in the chaos of war.

Denis titled the sketch “Sentinel” and signed it with his customary DB in the corner. Then he blew out the candle and fell into exhausted sleep, still wearing his flight clothes, too tired even to remove his boots.

He dreamed that night of a harbor he had never seen—not the Grand Harbour as it was now, but as it had been decades earlier. Of children skipping stones across water that reflected no warships, no smoking ruins. Of a boy and girl sitting side by side on a sea wall, their futures still unwritten.

In his dream, the girl turned to look at him, and he saw his own eyes looking back.

I could not reach his dreams. Could not tell him what his heart was trying to reveal. But I stayed near, wrapping my awareness around the metal buttons of his uniform, the coins in his pocket, the springs of his bed. Keeping watch as he had kept watch over Malta.

The next morning, he woke to the now-familiar wail of air raid sirens. Another day. Another battle. Another chance to hold back the tide of destruction falling from the sky.

Brush strokes capture pain Artist's eye sees beauty still Memory preserved

BREAD – JUNE 1942

The bakery on Merchant Street had stood for three generations, its stone walls absorbing the scents of bread and pastry until they seemed to exude warmth even when the ovens were cold. Antoni Calleja had worked there since boyhood, beginning as an apprentice, then baker, then owner when his father-in-law passed.

At forty-two, his hands were strong from decades of kneading dough, his forearms marked with the small burns that were a baker’s badge of honor. Each morning, even during the siege, he rose at three to light the ovens, to prepare what little bread could be made with increasingly scarce flour.

His wife, Censa, would join him by five, bringing their two sons—Peter, age four, full of questions and energy; and Joseph, just one, solemn and watchful even as an infant. The children would sleep on flour sacks in the back room while their parents worked, serving the long lines of Maltese who came with ration cards and desperate eyes.

“The bread is hope,” Antoni would say when Censa worried about the dwindling supplies. “As long as there is bread, there is tomorrow.”

On June 15th, 1942, Antoni went to the bakery alone. Censa had been up all night with Joseph, who had developed a fever. She needed rest, and so Antoni had kissed her forehead in the darkness and promised to manage without her.

“I’ll bring home something special,” he said at the door. “Perhaps a small honey cake for the boys.”

She touched his cheek, feeling the familiar roughness of his beard. “Be careful.”

“Always, my love.”

The air raid that morning came earlier than usual. The bombs fell in a pattern that suggested the German pilots had finally identified the bakery as a target—a small blow against Maltese morale, against the daily bread that sustained not just bodies but spirits.

The first explosions struck nearby buildings, sending debris cascading onto Merchant Street. Antoni herded customers and assistants into the stone cellar beneath the bakery—a space reinforced with timbers that had once been ship masts, ancient wood that had already withstood centuries of storms.

But not all bombs fall at once. Some are designed to wait, to create a false sense of security before completing their deadly work.

I felt it above the bakery—a 250-kilogram delayed-action bomb, its timing mechanism counting down while rescue workers arrived, while people emerged believing the danger had passed.

I reached for it as I had reached for the Mosta bomb. Tried to penetrate its casing, to disrupt its mechanism, to freeze its terrible purpose.

But it was different—a new design with shielding I could not penetrate fully. I was exhausted, each time I manipulate I drain. I managed only to delay, not prevent. To give minutes, not salvation.

“Get back!” Antoni shouted when he saw people returning to the street. “There’s another—”

The explosion erased his last words. The bakery’s front wall collapsed inward, burying Antoni and three rescue workers beneath limestone and timber.

At home, Censa sat upright in bed, woken from uneasy sleep by a sound too distant to have disturbed her. Joseph stirred in his crib beside her. Peter, playing quietly on the floor, looked up with wide eyes.

“Mama? What was that?”

She knew. Even before the neighbor knocked on her door, breathless and hesitant. Before the words were spoken that would divide her life into before and after.

She knew.

Three hours later, she stood in the ruins of the bakery, her sons held tightly by her mother in the safety of a nearby shelter. Workers still cleared debris, but hope had faded. No one could have survived the collapse.

Then a shout—they had found him. Beneath a fallen timber that had created a small pocket of space. Protected by flour sacks that had absorbed some of the impact.

Antoni Calleja. Baker. Husband. Father.

Dead.

Censa did not cry as they brought him out. Did not scream or wail or collapse as other war widows sometimes did. She simply stood straight, her face set in lines of granite, and nodded when they asked if this was her husband.

“I will take him home,” she said.

She buried silence twice. Once in 1919, when she stood in the rain as a child and watched them lower her cousin Manwel into the ground. Again now, as a woman, as Antoni was laid beside his father in the small cemetery outside Żejtun.

She had become a keeper of graves. A guardian of memory. A witness to the price of loving Malta too much.

Widow stands unmoved Children clutch her like anchors Family forged in fire

THE TWO PATHS – 1945-1960

The small house in Żejtun became a world unto itself for Peter and Joseph Calleja. The courtyard with its single lemon tree. The stone steps worn smooth by generations. The small kitchen where their grandmother taught them to roll pasta dough while bombs fell in the distance.

As the war slowly turned, as Malta’s siege gradually loosened, the brothers grew. Peter started school, thriving despite shortages of books and paper. Joseph remained at home longer, helping his grandmother with small tasks, watching his mother sew and paint with equal fascination.

On the day the war officially ended in 1945, a celebration filled Żejtun’s main square. Peter, now seven, danced with other children around a bonfire. Joseph, four, stayed close to Censa, watching the flames with wary eyes.

“Is the bad men gone forever?” he asked her.

Censa smoothed his hair, choosing her words carefully. “These bad men, yes. But there will always be others. That’s why we must be strong, little one.”

“Like Papa was?”

“Like Papa was.”

When Peter was ten and Joseph seven, Censa opened a small shop in the front room of the house. Part seamstress, part art studio, where she sold her paintings to tourists beginning to return to Malta, and repaired clothing for locals still rebuilding their lives. The boys helped after school—Peter charming customers with his quick smile, Joseph silently tallying accounts with surprising precision.

As they entered their teenage years, their different natures became even more pronounced. Peter excelled in languages, in literature, in subjects that opened windows to the wider world. Joseph found his strengths in mathematics, in organization, and increasingly, in a fierce pride for Malta that sometimes alarmed his teachers.

By 1958, when Peter was twenty and Joseph seventeen, their paths were already diverging. Peter had secured a position with a shipping company, learning skills he hoped would eventually take him abroad. Joseph, finishing school with high marks in mathematics and sciences, was drawn to military service with an intensity that surprised even his mother.

“The army needs men who will stand up for Malta,” a recruiter told him. “Men who remember what it means to be Maltese.”

Joseph had nodded, his normally reserved demeanor giving way to unusual animation. “I’ve seen how the British run things,” he said. “We need our own people in positions of authority.”

The recruiter had smiled. “With your temper and your brains, you could go far.”

When Joseph brought home papers to enlist, Censa noticed the fierce gleam in his eye—the same look her her father used to have when talking about their cousin Manwel. A passionate conviction that bordered on recklessness.

“You’re certain?” she asked.

“Never more certain of anything,” Joseph replied, his voice hard with determination. “Someone needs to ensure Malta is protected by Maltese, not just used as a convenient naval base.”

Censa signed the papers without further comment. That night, she painted later than usual—a canvas showing a soldier standing at the harbor’s edge, his back to the viewer, his posture suggesting both strength and a dangerous solitude.

I watched both boys, so different yet bound by loss. Peter climbing, questioning, always seeking beyond the walls that contained him. Joseph quiet, observant, his small hand often reaching for the stone of the house as if to anchor himself.

By 1960, Peter worked full-time for the shipping company, saving every penny toward his dream of emigration. Joseph had entered military training, his natural discipline and mathematical mind making him well-suited to the structured environment, though his superiors noted his quick temper when British officers made dismissive comments about Malta’s readiness for independence.

Brothers in contrast One dreams outward, one inward Same blood, different paths

BYE – 1960-1968

As Malta slowly rebuilt after the war, Denis Barnham remained. When most British personnel were reassigned to other theaters, he requested to stay. Having survived the siege when so many others had not, he felt a duty to the island’s defense that went beyond ordinary military assignment.

But his role changed. From Spitfire pilot to staff officer. From front-line defender to administrator. His official responsibilities expanded to include liaison work between British forces and local authorities—work that increasingly meant protecting British interests as Malta’s push for independence gained momentum.

“They’re moving too quickly,” he told his commanding officer in 1956, after a particularly tense meeting with Maltese nationalist leaders. “They don’t understand the strategic importance of maintaining proper military facilities here. The Cold War is real, and Malta’s position is critical.”

“That’s precisely why we need you, Barnham,” the general replied. “You understand both sides. They trust you more than most of us.”

Denis nodded, accepting the compliment but feeling the weight of divided loyalties. He had grown to love Malta deeply, but his duty to Britain remained paramount. His orders were clear: ensure continued British military presence even after independence, secure favorable terms for base leases, maintain Malta’s position within the NATO security framework.

He married a woman from Gloucestershire who adapted admirably to Mediterranean life. They had two daughters who grew up speaking English at school, learning just enough Maltese to get by. Unlike many British personnel, who lived in enclaves apart from the local population, Denis insisted on integrating into Maltese society—attending local events, exhibiting his artwork, maintaining connections with islanders who had worked alongside the RAF during the siege.

But as nationalism grew stronger, he found himself increasingly caught between worlds. The Maltese who had once embraced him as a defender now sometimes viewed him with suspicion—an agent of colonial power rather than an ally.

“Times are changing, sir,” a young Maltese clerk told him once, after a terse exchange over base access protocols. “People want their island back.”

“I helped save this island,” Denis replied, more sharply than he intended. “Britain has protected Malta for generations.”

“And used it,” the clerk said quietly before walking away.

The incident troubled Denis more than he cared to admit. Walking home that evening, he found himself studying the ancient fortifications of Valletta with new eyes—seeing them not just as beautiful architecture but as the physical manifestation of outside powers controlling this strategic island for their own purposes. Phoenicians, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Knights, French, British—an endless procession of rulers.

And yet, something in him bridled at the thought of Malta drifting from British influence, potentially aligning with powers less benevolent, less committed to democracy and rule of law.

I felt his internal conflict—the pull between his genuine love for Malta and his deeply ingrained sense of duty to Britain. The tension between the blood that recognized these shores and the upbringing that had shaped his worldview.

I could not reconcile these forces for him. Could not tell him that he served two homelands, not one. That the conflict he felt was written in his very cells.

His career continued to advance. By the early 1960s, he had risen to become one of the senior British military representatives in Malta, deeply involved in the delicate negotiations leading toward independence. His reputation for fairness made him valuable to the transitional process, though his fundamental mission remained protecting British strategic interests.

As these negotiations intensified, he occasionally crossed paths with Joseph Calleja, first as a promising cadet, later as a rising officer in Malta’s developing military structure. Something about the young man’s intensity, his barely contained fervor for Maltese sovereignty, made Denis uneasy. He recognized in Joseph the kind of nationalist passion that could easily tip into recklessness.

“Lieutenant Calleja shows great promise,” a British training officer reported. “Brilliant tactical mind. Natural leader. But keeps his emotions too close to the surface. Especially regarding political matters.”

Denis made a note to watch the young officer’s career. Malta would need disciplined, level-headed military leaders as it moved toward independence, not firebrands who might destabilize the delicate balance of Mediterranean power.

“Keep him challenged intellectually,” Denis advised. “Give him complex problems to solve. His mind needs to control his temperament, not the other way around.”

Son defends empire Island's blood calls from within Duty wars with bone

LETTER FROM ABROAD – 1970

The envelope arrived bearing exotic stamps and postmarks that spoke of distance. Censa sat at the small kitchen table, turning it in her hands before carefully slitting it open with a knife worn thin from years of use.

Joseph watched from the doorway, his uniform crisp and new, his face unreadable.

“From Peter,” Censa said, though she didn’t need to. They both recognized his handwriting.

I felt the paper between her fingers. The small metal clasp of the airmail envelope. The ink that had traveled halfway around the world to find its way back to Malta.

Dearest Mother and Joseph,

Sydney is everything I imagined and more. The shipyard work is steady, and they value my experience from Malta. The house I’ve rented is small but has a garden where I can grow lemons like ours at home.

I’ve met someone, Mother. Her name is Diana. She’s studying at university—science, of all things. Her parents came from Greece after the war. She understands what it means to carry your homeland in your heart while building a life elsewhere. I’ve told her all about Malta, about you both. She wants to visit someday.

The sea here is different—wilder, deeper blue. Sometimes I stand at the harbor and try to feel if Malta might be on the other side, but there’s only the vast Pacific. Still, I’m not alone with my thoughts like I feared.

Joseph, how is your training? Mother writes that you’re excelling. I’m not surprised. You always understood duty better than I did.

I miss you both. But I don’t regret leaving. There is space to breathe here, to become something new while remembering what was.

All my love,

Peter

Censa folded the letter carefully, returning it to its envelope. Joseph remained in the doorway, his shadow stretching across the floor between them.

“He sounds happy,” she said finally.

Joseph nodded once, then turned away. “I have duty in an hour,” he said, voice flat. “I won’t be back until late.”

Censa watched him go, noting the stiffness in his shoulders. She touched the letter again, feeling both pride and loss. One son finding his horizon, the other digging deeper roots into Malta’s limestone.

I could not reach them with words, these children of my soil. Could not tell Joseph that his brother’s departure was not abandonment. I could not tell Peter that he was safe now, he was a man of strength and courage. He has a father less child hood, many a night he cried and felt the pain of his absent father. A father that perished because of the conquerors and the would be enemies inflicting merciless pain on this land.

Six months later, another letter arrived with news of Peter’s marriage. A year after that, a photograph: Peter and Diana standing outside a small weatherboard house, her belly rounded with the promise of new life.

Censa placed it on the mantelpiece, next to the small silver Maltese cross that had been her own mother’s. Joseph barely glanced at it when he visited, but she noticed how his eyes sometimes lingered on the space behind it, on the emptiness his brother had left behind.

By 1972, Peter’s letters spoke of a daughter named Celeste, “with eyes that seem to look through things rather than at them,” and a curiosity that left her parents breathless.

“Diana says she’ll be a scientist like her mother,” Peter wrote. “She’s already fascinated by the mineral collection Diana keeps. Holds the pieces of iron pyrite like they’re speaking to her.”

Censa read these passages aloud to Joseph during his increasingly rare visits. He would listen in silence, offering only the smallest nods, as if acknowledging transmissions from a foreign country whose language he refused to learn.

But in the night, alone in his quarters at the barracks, Joseph would sometimes take out the photographs his brother sent and study the face of the niece he had never met, wondering what she might see if she looked at him with those penetrating eyes.

I felt the connections stretching, thinning, but never breaking. Blood calling to blood across oceans. Memory flowing like current through the generations. I could not speak to them, but I could watch. And wait. For some bloodlines always return to their source, drawn by forces beyond their understanding.

A child is born far Iron calls to distant blood The circle waits, open