The Great Siege of Malta in 1565 marked one of history’s most intense standoffs, pitting the mighty Ottoman Empire against the smaller, fortified Order of the Knights of St. John. Beyond its military maneuvers and strategic brilliance, the siege was an immense financial endeavor for both sides. Each empire relied on their financial systems and fiscal strategies to support what became a prolonged and grueling engagement. For the Knights, this meant leveraging income from their territories and corsairing efforts, a strategy that would eventually lead to their decline, as explored in From Corsairs to Collapse. On the Ottoman side, the siege represented a massive logistical and economic challenge, further straining an empire already grappling with Mediterranean campaigns, detailed in The Ottomans After the Great Siege of Malta. The siege became not only a test of military might but also of economic endurance, demonstrating how both empires’ financial resilience reached its limits. For a detailed look into the financial strategies on both sides, see Finances of the Great Siege of Malta: A Dual Perspective.

The Financial Context of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire entered the 16th century as one of the most powerful empires in the world, with vast territories and a well-established tax system. However, the Ottoman financial structure was complex, relying heavily on a network of intermediaries and provincial elites, which affected its ability to mobilize resources directly for the central administration.

Ottoman Revenue Sources

The Ottoman revenue system was largely based on:

- The Timar System: Lands (timars) were granted to military officials in exchange for loyalty and military service. Timar holders collected taxes from peasants and were expected to maintain soldiers for the Sultan’s campaigns. However, this system’s decentralized nature often reduced the central treasury’s control over total revenues.

- Tax Farming and Provincial Elites: As the empire expanded, provincial tax farmers and local notables (ayan) gained influence over tax collection, often keeping a significant portion of the revenues. As much as two-thirds of revenue collected from certain regions never reached the central treasury, remaining under local control.

Financial Challenges and Siege Preparation

As the Ottomans planned the siege, funding was directed towards provisioning fleets, paying soldiers, and acquiring the latest artillery and siege weaponry. Financing such a large-scale operation was challenging given the complexities of the Ottoman financial system. The reliance on intermediaries meant that funds were often limited by the wealth and influence of provincial elites. Unlike European states with more centralized systems, the Ottoman Empire struggled to pull large reserves quickly from its provinces, a challenge further explored in The Ottomans After the Great Siege of Malta.

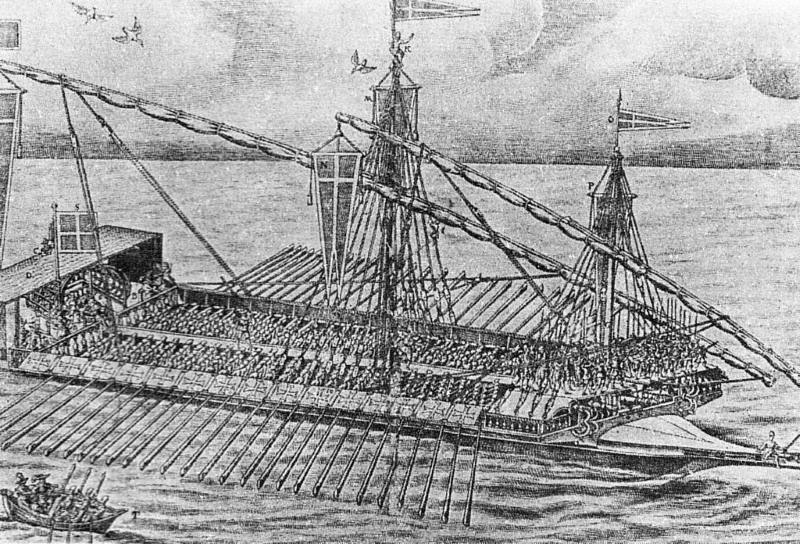

The Great Siege of Malta was a monumental financial undertaking for the Ottoman Empire, with one of the most substantial costs centered on maintaining a formidable maritime fleet. This fleet, vital for transporting troops, artillery, and supplies, was extensive, consisting of over 180 vessels, including war galleys, troop transports, and support ships. For more on how logistical and financial planning affected both sides during the siege. Here’s a breakdown of the key expenses incurred:

Maritime Fleet Costs

- Ship Construction and Maintenance: Building and equipping the galleys required skilled labor, from carpenters to ironworkers, along with a steady supply of materials like timber, pitch, and rope. Keeping these vessels operational, especially after long, arduous journeys, meant continuous repair work, which added significantly to the expense.

- Crew Salaries: Operating a fleet of this scale required a sizable crew. Experienced sailors, rowers, and oarsmen manned the vessels, with some being salaried and others conscripted or enslaved. The payroll for these crews, combined with the challenges of organizing and supporting a workforce of this size, contributed heavily to operational costs.

Logistical Costs

- Supply Chains: Transporting provisions, including food, water, gunpowder, and other essentials, over a long distance required meticulous planning. Ships not only carried soldiers but also maintained the flow of these supplies to Malta, which was far from the nearest Ottoman ports, demanding significant investment in both provisioning and securing supply routes across the Mediterranean.

- Siege Fleet and Equipment: The fleet alone, consisting of around 193 vessels, was outfitted with weaponry, ammunition, and provisions. Equipping each ship required extensive resources, and organizing consistent supply lines to support the siege fleet was a substantial logistical endeavor.

Soldier Pay and Incentives

- Janissaries

Pay Structure: The daily wage for a typical Janissary in the 16th century was around 2–3 akçe per day for ordinary soldiers. The figure of 20–40 akçe per day seems unusually high for that period.

Bonuses and Incentives: Janissaries did receive bonuses for acts of valor and were entitled to shares of plunder, which served as significant motivators during campaigns. - Sipahis (Cavalry)

Timar System: Sipahis were compensated through the timar system, receiving land grants from which they could collect taxes, corresponding to their rank and service.

While it’s plausible that the central treasury supplemented their income during campaigns, specific details about allowances for contingents from Karamania and Rumelia are not well-documented. - Adventurers and Volunteers

Adventurers: Volunteers and auxiliary troops often received modest wages or in-kind compensation such as rations and supplies. - Corsairs

Spoils of war : Corsairs from Tripoli and Algiers operated semi-independently and were primarily incentivized by shares of loot rather than regular salaries. - Religious Servants

Stipends: While they did receive modest stipends, their primary motivation was ideological, viewing participation as a religious duty. - Enslaved Labor

No Salaries: Enslaved workers were unpaid but required maintenance, which was a significant logistical and financial consideration for the Ottoman forces. - Commanders and Officers

Pay + Spoils of War: High-ranking officials like Piali Pasha and Lala Mustafa Pasha received substantial pay, shares of spoils, and rewards such as pensions and land grants for their leadership roles.

Artillery and Siege Technology

- Investment in Advanced Artillery: Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent ensured the Ottomans brought advanced siege technology to Malta to breach the defenders’ fortifications. The cannons, bombards, and other equipment, which had to be transported by sea, represented a significant cost in both procurement and maintenance, as they needed to remain functional throughout the siege.

Ottoman Financial Constraints During the Siege

The Ottomans faced challenges replenishing supplies and reinforcements as the siege wore on, largely due to the decentralized nature of their fiscal structure. Although the Ottoman Empire was vast and wealthy, its financial system lacked the ability to rapidly centralize funds for sustained campaigns. Provincial taxes often remained in the hands of local elites, who were reluctant to transfer resources back to the central treasury. As the siege became prolonged, the Ottomans’ resources thinned, affecting their ability to maintain a steady flow of reinforcements and supplies to Malta.

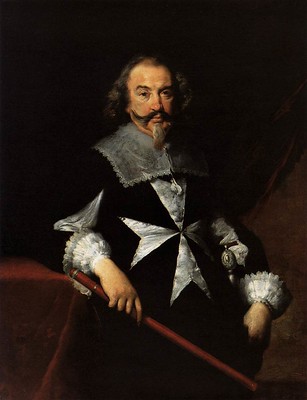

The Financial Context of the Knights of St. John

The Knights of St. John, though vastly outnumbered, leveraged their smaller but highly centralized financial system effectively. The order had developed a strong financial foundation through years of strategic planning and support from European monarchs, allowing them to withstand the siege’s pressures longer than the Ottomans had anticipated. See Also : The true cost of Malta’s forts

Sources of Revenue for the Knights

The Knights’ financial base was built on:

- European Support and Donations: Catholic monarchs and nobles across Europe provided financial aid, military supplies, ships, and manpower, all aimed at bolstering the defense of Christendom.

- Commanderies and Estates: A well-established network of European estates funded Malta’s defenses through agriculture, rents, and taxes, generating steady income for the Order.

- Church Tithes: The Order received a portion of church tithes from various regions, creating a reliable source of revenue to sustain their operations.

- Tax Exemptions: Operating tax-free in territories they controlled, the Order funneled what would have been state taxes directly into their own treasury.

- Local Taxes and Monopolies: Taxes on the Maltese population and monopolistic control over essential commodities like salt and grain added significantly to their income.

- Ransoms and Spoils of War: The Order profited from piracy and naval battles with the Ottomans, earning money through captured goods and ransoms.

- Centralized Treasury: An efficient financial system allowed the Order to quickly mobilize resources and plan strategically, especially during times of siege.

- Land Taxes: Farmers and landowners were taxed based on the productivity of their land. These taxes often took the form of tithes on crops or livestock.

- Trade and Commerce: The bustling Tunisian ports, vital hubs of Mediterranean trade, were taxed heavily through customs duties and market fees, ensuring a steady flow of income.

- Sequestering Land: Strategic parcels of land were seized or acquired to build fortifications, store supplies, and create defensible positions, further strengthening their hold over the island.

Siege Expenses for the Knights

The defense required extensive funds, particularly as the siege progressed:

- Fortification and Defensive Infrastructure: Much of the Knights’ wealth had been invested in fortifying Malta’s defenses, particularly Fort St. Elmo, Fort St. Angelo, and Fort St. Michael. These fortifications required regular maintenance, and significant resources were allocated to repair and reinforce structures under heavy bombardment.

- Arms and Ammunition: Though outgunned by the Ottomans, the Knights ensured they were well-stocked with arms and ammunition. Cannons, muskets, and gunpowder were costly but essential for Malta’s defense. Each time the Ottomans breached a section of a wall, resources were quickly funneled to repair and reinforce it.

- Soldier and Local Militia Pay: The Knights needed to pay and provision their forces, which included professional soldiers and local militias. Although they offered fewer incentives than the Ottomans, the Knights provided enough support to maintain morale among the defenders.

External Financial Support During the Siege

The Knights of St. John benefited from continued financial and logistical support from European allies:

- Spanish Support: Philip II of Spain saw Malta as a key buffer against Ottoman expansion into Europe. Spain’s financial backing included regular shipments of supplies and additional soldiers, which helped offset the Knights’ limited manpower and resources.

- Papal Aid and Other Donations: The siege was framed as a struggle for Christendom, drawing support from across Europe. Financial contributions from Italian and French nobles bolstered the Knights’ resources. The Pope also encouraged donations from wealthy Catholic individuals, enhancing the Knights’ financial ability to withstand the siege.

Financial Outcomes and Implications of the Siege

The siege’s costs strained both the Ottoman Empire and the Order of the Knights of St. John, but its aftermath underscored the financial resilience and strategic advantages of a centralized fiscal system.

Ottoman Financial Exhaustion

The siege marked one of the first instances where Ottoman financial limitations were exposed. Despite their wealth, the decentralized system of tax collection hindered rapid resource mobilization. The siege proved costly, consuming a significant portion of the treasury allocated for Mediterranean campaigns, and ultimately, the Ottomans had little to show for their investment. This defeat forced the Ottomans to reconsider their fiscal strategies, eventually pushing for gradual centralization efforts, although meaningful changes only took shape in later centuries.

The Knights’ Financial Triumph

The Knights emerged victorious largely due to their effective financial and logistical management. Their centralized treasury enabled them to allocate resources swiftly and effectively, ensuring a continuous defense against Ottoman advances. Additionally, their strong relationships with European powers allowed them to receive critical financial and logistical support throughout the siege. Key to this success were the defenses of the Three Cities—Birgu, Cospicua, and Senglea—which formed the backbone of Malta’s resistance. This victory cemented Malta’s strategic role in defending Europe and underscored the effectiveness of centralized financial planning.

Conclusion: Financial Lessons of the Great Siege

The Great Siege of Malta serves as a case study in the financial dynamics of warfare, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of centralized versus decentralized financial systems. For the Ottoman Empire, the siege exposed the limitations of a financial system heavily reliant on intermediaries. Although the empire was vast and wealthy, it lacked the capacity to efficiently mobilize resources, a limitation that influenced its long-term military strategies.

In contrast, the Knights of St. John demonstrated the resilience of a centralized fiscal system supported by external alliances. Their ability to withstand the siege hinged on the efficient allocation of resources and strong financial backing from European allies. This centralization, combined with their strategic maritime operations, also reflected the economic role of corsairing during the siege, as detailed in The Knights’ Corsairing and the Great Siege of 1565.

The siege underscored the critical role of finance in sustaining military campaigns and foreshadowed the increasing importance of centralized taxation and revenue systems in Europe’s emerging fiscal-military states. After the siege, the Knights of St. John leveraged this centralized model to expand their fortifications, as seen in their continued investments in areas like Bormla, explored in Bormla’s Fortifications: A History of Strategic Defense.

The Great Siege of Malta remains an enduring symbol of resilience and strategic financial planning in warfare, illustrating how economic structures shape not only the outcome of battles but the course of empires. For a look at how the Knights evolved following their victory, see The Knights of Malta After the Great Siege.

This comprehensive analysis explores how financial strategies and structural constraints shaped the siege’s outcome, offering insights into the critical role of economic planning in military success.

References:

- The Fortification of Malta, 1530-1798: The Impact on the Maltese. University of Malta.

- Study on the Economic Impact of Warfare on Maltese Society. University of Malta.

- War Finance in the Ottoman Empire. 1914-1918 Online Encyclopedia.

- The Economic History of Ottoman Warfare. London School of Economics.

Disclaimer: Some details about salaries, troop numbers, and financial arrangements during the Great Siege of Malta are hard to pin down because historical records aren’t always consistent or complete. The value of the akçe also fluctuated back then, making it tricky to gauge its worth.