Maltese Carnival: A 500-Year Spectacle of Satire, Scandal, and Street Magic

Hey, fellow wanderers and history nerds! If you’re plotting a trip to Malta in February, mark your calendars: February 13–17), you’re in for more than just confetti and costumes. This isn’t your average festival—it’s a living, breathing rebellion that’s been flipping society’s script since the 1400s. Picture knights in drag rioting against Jesuits, greasy pole scrambles for live rabbits, and floats roasting everything from Ottoman invaders to modern crypto flops.

Drawing from dusty archives and fresh academic digs, this post uncovers the hidden layers of Maltese Carnival, blending wild tales from the past with the raw energy that still pulses through Valletta and Gozo today. We’ve gone deeper here, pulling in overlooked artistic theories, undervalued 20th-century masterpieces, and bold proposals for year-round cultural immersion.

Let’s dive in, from pagan roots to today’s Gozo chaos.

The Ancient Spark: From Butcher Bills to Knightly Blowouts

Carnival’s Maltese roots aren’t glamorous—they kick off with a 1482 city council debate where the Captain argued “no tax had to be collected until the successive Carnival,” treating it like a sacred holiday. By the early 1400s, it was all about pre-Lent feasting, with Sicilian influences bringing masks and dances. Fast-forward to 1535: The Knights of St. John arrive, and Grand Master Piero del Ponte turns Birgu into a jousting arena, prepping for Ottoman threats under the guise of fun.

But 1560? That’s when things got legendary. Grand Master Jean de Valette greenlit public masks amid a storm-trapped Christian fleet in the Grand Harbour. Admiral Doria, bored out of his mind from weather and plagues, let his crew loose: “the flower of the European chivalry and aristocracy made noisy, fun, dance and masks as Malta had never seen before.” Imagine galleons decked in silk and fireworks—your modern yacht party has nothing on this.

Deeper dive (key facts in bullets):

- 🕰️ Early accounts by Giacomo Bosio pinpoint the Knights’ arrival as Carnival’s formal start, but it likely simmered pre-1530 with scant records—hinting at lost indigenous vibes blending Mediterranean folklore.

- 🔍 Pre-Knights evidence remains scarce, suggesting possible indigenous or Mediterranean influences not commonly detailed.

- ⚔️ Social inversion core: Echoing Roman Saturnalia’s role-reversals, where slaves bossed masters—blueprint for today’s “King Carnival” elections in Valletta.

Why it vibes today: These role-reversals echo “Game of Thrones” uprisings. In 2026, snag a spot at Valletta’s Republic Street for floats blending ancient satire with AI jabs.

Knightly Drama: Riots, Bans, and the Greasy Pole Hustle

The 1600s were peak scandal season. In 1639, Grand Master Giovanni Paolo Lascaris issued an edict restricting women’s attendance at Jesuit theatrical performances during Carnival to prevent “scandali, che in quei giorni Carnevaleschi avvenir potevono.” Cue riots: Young Knights pelted the Jesuit college with stones, chanting against their “beards,” and plastered cartoons of Lascaris as a “half-donkey spurred by a Jesuit” (“il G. M., che dal mezzo in giù era somaro, et un gesuita con un puntone lo faceva camminare”). Jesuits got booted temporarily—talk about Carnival chaos birthing idioms like “Wiċċ Laskri” for a sourpuss.

By 1721, Grand Master Zondadari added the kukkanja: A 30-foot greasy pole in Palace Square, dangling hams and critters. Winners feasted amid the melee. And don’t miss the parata (or battitu): An 18th-century mock sword fight, with 1774 contracts fining absent dancers 65 scudi—serious business for Żebbuġ troupes.

Deeper dive (key facts in bullets):

- 🕰️ Inquisition records reveal deeper piety-power clashes, with Jesuits countering excesses via “Forty Hours’ devotion” to “impedire in ogni maniera con la sua autorita l’offese pubbliche, che qui si fanno a Dio in ogni tempo, e massime nei giorni di carnovale.”

- 🔍 The “large stone” at the gallows signaled mask permission, a quirky ritual from 1762 diaries.

- ⚔️ The battitu evolved from siege reenactments, with contracts ensuring troupe participation amid fines.

- 📜 Devil outfits banned in 1639 but later lifted, reflecting social performance where prohibitions affirmed rank.

Modern hook: These brawls? Prototype for Nadur’s no-rules drag devils. Pro tip: Hunt the pole’s base remnants in Valletta for a hidden gem selfie.

Colonial Twists: Tragedies and Power Plays

British rule (1800–1964) dialed up the drama. Costumes became tools for “social performance,” letting folks punch up at rank—think masks hiding class jabs, with prohibitions affirming colonial power. But 1823? Heartbreaker: 110 boys crushed in a convent during bread handouts post-Carnival. In 1846, a Sunday mask ban sparked pet animals dressed as clergy—nearly riot-level shade.

Power dynamics? Carnival flipped colonial scripts, with floats mocking Brits until a 1936 satire ban (axed in 2013). Post-1926 centralization in Valletta built a “feel-good factor,” turning float skills into film set magic.

Deeper dive (key facts in bullets):

- 🕰️ 19th-century eyewitnesses described “micrological” power plays in balls, where costumes enabled aspiration but reinforced status—drawing on Bourdieu and Geertz theories for social theater.

- 🔍 The 1936 ban stifled anti-colonial jabs, but post-WWII revivals saw floats channeling national pride.

- ⚔️ Echoes in Valletta F.C.’s mock funerals roasting rivals—like a bishop dragging Queen Elizabeth II.

- 📜 Centralization fostered skills transfer, from float-building to modern industries.

Today: Echoes in Valletta F.C.’s mock funerals roasting rivals—like a bishop dragging Queen Elizabeth II. For 2026, catch the vibe in Floriana’s competitions.

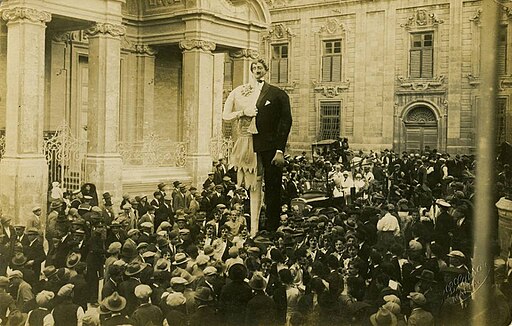

Salvatore Lorenzo Cassar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gozo’s Raw Edge and Modern Revivals

Gozo’s Carnival? Organized since 1952, but waning by the ’90s due to social shifts—yet Nadur’s spontaneous grotesques thrive, like priests in latex or toilet politicians. The qarċilla? Bawdy 1760 farces with lines like “żobb ta’ ħmar,” revived in 2014 for wedding parodies. And il-Qarinża? A fading New Year’s mock-death ritual with lime for luck.

Post-1964 independence amped national pride, with floats as “imaginative art” per Bakhtin—often snubbed but genius. Notting Hill twinning since 2014 adds global flair.

Deeper dive (key facts in bullets):

- 🕰️ Applying Roger Caillois’ theories, Gozo’s “performative philosophy” contrasts Valletta’s polish—waning traditions from agricultural communities give way to symbolic inversions in mock funerals.

- 🔍 Proposals push for year-round “hands-on cultural experiences” like costume-making workshops, tapping cruise markets to preserve UNESCO heritage amid seasonal limits.

- ⚔️ The 1952 organization marked a shift, but by the 1970s, house visits and lime rituals faded in places like Marsa and Floriana.

- 📜 Risqué spontaneity persists, with Nadur’s no-floats lunacy echoing early inversions.

Summer Carnival Extensions: Bringing the Fest to St Paul’s Bay and Marsascala

Carnival isn’t just February anymore—enter the Summer Carnival, a modern twist to keep the party rolling. Launched in 2013, it hit its fifth edition by 2017, spreading vibes across the islands.

Deeper dive (key facts in bullets):

- 🕰️ Introduced in 2013 as an extension of the traditional fest, organized by Festivals Malta to boost tourism beyond Lent.

- 🔍 St Paul’s Bay debut: Hosts the first two days (e.g., August 23-24 in recent years), with parades, floats, and dance troupes along the promenade.

- ⚔️ Marsascala introduction: Caps the event on the final day (e.g., August 25), featuring vibrant street celebrations—first time with a full promenade parade in 2021 after a four-year hiatus.

- 📜 Why it started: To revive waning traditions and attract summer crowds, with 11 floats and 10 dance companies in early editions, plus bands and kids’ programs.

Perfect for 2026 visitors—hit the August edition for beachy vibes post-main event.

Artistic Legacy: Undervalued Masterpieces of the 20th Century

Here’s where it gets artsy: 20th-century grotesque masks and floats? Pure “imaginative quality,” yet “looked down on” despite pioneering artists’ sketches and designs. George Glanville nailed it: “both [Carnival and art] should not be separated from one another.” From programme covers to photos, these works blend history with flair, undervalued due to separation from mainstream art spheres.

Deeper dive (key facts in bullets):

- 🕰️ Mikhail Bakhtin’s inversion theories spotlight how Malta/Gozo differences—structured vs. spontaneous—echo ancient roots, with limited pre-Knights material hinting at lost creativity.

- 🔍 Artists like Glanville pushed for recognition, with 20th-century pieces pioneering techniques now in film and tourism.

- ⚔️ UNESCO status highlights this legacy, proposing extensions like workshops to bridge gaps in off-season tourism.

- 📜 Often “downgraded” despite contributions, these masterpieces show Carnival’s evolution from Baroque to modern global fusion.

Notable Figures: Pioneers and Preservers of Maltese Carnival

Carnival’s story is shaped by visionaries who sparked, scandalized, and saved it. Here’s a spotlight on key players, from historical heavyweights to modern guardians.

Deeper dive (key facts in table):

| Figure | Role & Era | Contributions & Legacy |

|---|---|---|

| Grand Master Piero de Ponte | Formalizer (1535, Knights era) | Officially introduced tournaments in Birgu, boosting Carnival from modest feasts to knightly spectacles—credited as the “father” of organized events. |

| Grand Master Jean de Valette | Innovator (1560, Knights era) | Permitted public masks and ship floats during a storm, turning harbors into party zones; his leadership post-1565 Siege infused national pride. |

| Grand Master Giovanni Paolo Lascaris | Controversial Reformer (1639, Knights era) | Banned women’s masks and devil costumes, sparking riots and the “Wiċċ Laskri” idiom—highlighted piety vs. revelry tensions. |

| Grand Master Marc’Antonio Zondadari | Game-Changer (1721, Knights era) | Launched the kukkanja greasy pole, adding chaotic fun; his rule saw Carnival peak as Baroque excess. |

| Fr. Felic Demarco | Folk Dramatist (1760, Knights era) | Penned the first known qarċilla, a bawdy farce—preserved obscene rhymes that evolved into modern street theater. |

| Pietro Paolo Zahra | Artist (1685-1747, Knights era) | Documented 18th-century festivities through carvings and works, linking Carnival to Baroque art heritage. |

| Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) | Influencer (1571-1610, Knights era) | Fled to Malta as a fugitive; his dramatic style inspired grotesque masks and satirical art, tying Carnival to Renaissance flair. |

| George Glanville | Modern Advocate (20th century) | Championed floats as “imaginative art,” arguing they shouldn’t be separated from fine art—fought undervaluation. |

| Vicki Ann Cremona | Preserver/Scholar (Contemporary) | Academic whose works (e.g., on Gozo waning traditions) document and revive history, influencing UNESCO recognition. |

| Jeremy Boissevain | Anthropologist (Contemporary) | Explored Carnival’s play and politics in colonial Malta, aiding preservation through scholarly insights. |

These folks didn’t just party—they preserved a cultural lifeline, from de Ponte’s formalization to Cremona’s modern advocacy.

Timeline of Maltese Carnival Milestones

To scan the evolution at a glance:

| Era/Year | Key Event | Details & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Early 1400s | Meat price regulations signal early feasts | Tied to Sicilian masquerades; social inversion core. |

| 1535 | Formalized under Piero del Ponte | Began in Birgu with knightly games; complaints over excesses. |

| 1560 | Valette’s reprimand for harbor festivities | Masks banned outside Carnival; bad weather sparked scandals. |

| 1639 | Lascaris Bando bans women/masks | Led to Jesuit unrest, arrests, and “Wiċċ Laskri” idiom. |

| 1721 | Kukkanja introduced | Pole scramble; visible remnants today in Valletta. |

| 1760 | First qarċilla by Fr. Felic Demarco | Obscene rhyming marriage farce. |

| 1823 | Convent crush tragedy | ~110 boys suffocated post-Carnival. |

| 1846 | Animal clergy costumes near-riot | Response to mask ban; tense religious relations. |

| 1926 | Centralized in Valletta | Committee prizes; decline in villages. |

| 1936 | Satire ban | Curbed anti-colonial floats. |

| 1952 | Gozo organized | Nadur’s grotesque, spontaneous style emerges. |

| 1964+ | Post-independence | UNESCO heritage; modern floats mix global influences. |

| 2013 | Summer Carnival introduced | Extended tradition to August, starting in St Paul’s Bay and Marsascala for tourism boost. |

| 2014 | Qarċilla revival and Notting Hill twinning | Inclusive dances; satire returns. |

Why Malta Carnival Still Hits Different

In our filtered world, Carnival strips it back: Raw satire on power, blending “Stranger Things” lore with local jabs. It’s therapy—laugh at the madness, then Lent it go. Your story: “Danced with devils in Malta.” Beat that.

Ready for 2026?

Book ferries early. Pack a mask. Dive into the mayhem. Malta Carnival Festival

References

- Cremona, V.A. (1995). Carnival in Gozo: Waning Traditions and Thriving Celebrations. Journal of Mediterranean Studies, 5(1), 68-95.

- Boissevain, J. (2018). Carnival and Power: Play and Politics in a Crown Colony. Palgrave Macmillan. Link

- Mifsud-Chircop, G. (2002). Carnival Folk Drama in Malta. Folk Drama Studies Today. Link

- Cremona, V.A. (2016). Costume in Carnival: Social Performance, Rank and Status. Studies in Costume & Performance. Link

- Allen, J. (2012). Anti-Jesuit Rioting by Knights of St John During the Malta Carnival of 1639. The Historical Journal. Link

- Fenech, J. (2024). Carnival’s Socio-Cultural Effect on Valletta Society Post 20th Century. HND Thesis, University of Malta. Link

- Cremona, V.A. (2018). Circuses, Power and Piety: Carnivals in Malta During the 17th and 18th Centuries. In A. Buttigieg & C. Cassar (Eds.), Malta in the Baroque Age. Link

- Cremona, V.A. (2015). The Carnival Battitu or Parata in the Eighteenth Century. The Journal of Maltese History. Link

- Cremona, V.A. (2018). Knights, Jesuits, Carnival, and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century Malta. The Historical Journal. Link

- Cremona, V.A. (2018). The Admiral and the Carnival. Academia.edu. Link

- Buhagiar, K. (2015). The Maltese Carnival as an Artistic Expression in Maltese Culture. B.A. (Hons) Dissertation, University of Malta. Link

- Gauci, A. (2023). Maltese Carnival Product Development. B.Sc. (Hons) Dissertation, University of Malta. Link