Introduction: The Forgotten Theater

World War I began in August 1914, triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. On one side stood the Central Powers – Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. Against them, the Allies – primarily Britain, France, Russia, Italy (from 1915), and later the United States (from 1917). The war would last until November 1918, claiming over 17 million lives.

Malta, a small British-controlled island in the Mediterranean, found itself suddenly crucial to the war effort. Too far from the trenches of France to hear the guns, too close to enemy submarines to feel safe, Malta became something unique: a fortress, a hospital, a supply base, and a laboratory for new military technology – all while its civilian population struggled with the most basic necessity of life: bread.

By 1917, the third year of the war, Malta was experiencing what every wartime economy faced: massive inflation. Food prices globally had risen by almost 30% that year alone. In Austria-Hungary, prices were doubling annually. In the United States, food costs would increase by over 80% between 1917 and 1920. But statistics tell only part of the story. In Malta, the crisis had a particular character, shaped by the island’s isolation, its strategic importance, and the peculiar mix of cutting-edge military technology and medieval living conditions that defined life on the fortress island.

The Island of Unlikely Allies

In November 1917, six peculiar sheds went up along the Lazaretto Creek shore of Manoel Island. Each housed a single kite balloon – cutting-edge technology for spotting enemy submarines. These weren’t children’s toys but serious military hardware, tethered to ships and floating high above the Mediterranean, with observers in baskets scanning for periscope wakes.

Think about that for a moment. While the Wright Brothers had flown just 14 years earlier, and military aviation was still in its infancy (those Italian FBA flying boats that arrived in Malta in August 1917 could barely stay aloft), the British were already innovating with balloons as anti-submarine weapons. Commander-in-Chief Admiral Sir Somerset Gough-Calthorpe had personally pushed for their introduction. They even built a gas plant to fill them.

This was Malta in 1917: a strange mixture of medieval suffering and space-age innovation.

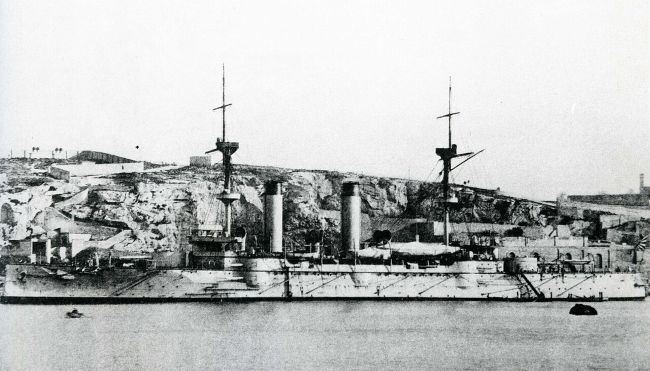

The harbour that year hosted an unusual gathering. Japanese destroyers – the Hinoki, Kashi, Momo and Yanagi – arrived in August 1917 to operate alongside the Royal Navy. On a ceremony aboard the flagship Idzumo, British decorations were presented to Japanese officers. Rear-Admiral G.A. Ballard was there, along with Captain Paul Methuen representing the Governor.

Twenty-eight years later, these same navies would be trying to sink each other across the Pacific. But in 1917, Japanese sailors were dying to protect British convoys in the Mediterranean. History has a dark sense of humor.

The Italians were there too. Five Italian FBA flying boats supplemented the British Short 184s, hunting submarines from RNA Station Malta. Another future enemy, another temporary friend. The Great War made strange bedfellows, and Malta’s harbours hosted them all.

Even the French Navy was based here – until that summer when they mysteriously relocated to Argostoli in Greece. Officially, it brought them closer to their operational area in the Aegean. Unofficially? The French sailors had discovered Strait Street, and Malta’s prostitutes were giving them more than they bargained for. Disease rates soared. The French decided Greek waters were healthier.

| Malta Short Let: Cozy Stay in Gzira | |

|

Sliema Area Modern Designer Finished 2 Bedrooms + Games Room. First floor with Maltese Balcony Large back Terrace with swinging sofa Fully Airconditioned + Full Kitchen 3 TVs, including 65” with backlight. |

|

|

Book Now: Google Travel | Direct (Cheapest) | Booking.com | Airbnb |

|

Where There Are People, There Is Trade

While admirals pinned medals on Japanese officers and flying boats took off from Marsaxlokk, ordinary Maltese faced a more basic problem: the bread, a stable in the Maltese kitchen was bad, very bad.

In July 1917, a frustrated resident wrote to the Daily Malta Chronicle describing their daily bread as “heavy unpalatable abomination.” Keep it more than a day and it would “turn sour and mouldy.” The writer had tried different dealers across the island – it was “all the same” terrible stuff everywhere. They suspected adulteration – and why not? When wheat is scarce and sawdust is cheap, when authorities are overwhelmed and bellies are empty, corners get cut.

This wasn’t German Kriegsbrot with its documented sawdust content. This was something else – too much moisture, perhaps, to increase weight and profits. Bad flour hoarded too long. Or simply the result of a supply system breaking down, where good intentions met the reality of submarine blockades.

The writer’s suggestion? Large co-operative stores would benefit every buyer. A simple idea that would take root decades later, but in 1917, it was just one voice crying out against profiteers and poisonous bread. (Read more about Malta’s food history)

And where systems break down, black markets flourish.

The contraband control service caught seven ships in 1917 alone: the Taxiarchi in January, an unnamed Greek caique in April, the Astrapi in June, the Jessmore on June 16, the Barrowmore on June 22, the Xiphias in July, and the Erato in December. Each carried goods that never reached official channels, never faced price controls. The authorities seized and auctioned the contraband, but who bought it? Not the poor queuing for mouldy bread. (Learn about Malta’s maritime piracy history)

By October 1917, the Valletta Police Court was overwhelmed with profiteering cases. Two dealers were fined £5 each for selling eggs at “excessive prices.” Another was hit with a £10 fine for using sugar in pastries without reporting stock in hand. These weren’t small sums – the Malta Labour Corps recruited men for just 2/6 per day, meaning those fines represented 40 to 80 days’ wages for a labourer.

Governor Methuen responded by setting maximum prices for foodstuffs on October 18, 1917. The government made it illegal not just to sell above these prices, but even to offer to buy at higher rates. But where there are people, there is trade. Where there is scarcity, there are those who profit from it. It’s as inevitable as gravity.

The Forgotten Technology Race

Back to those kite balloons. In an era before radar, before sonar was reliable, how do you spot a submarine? You go up. Way up. A kite balloon could lift an observer high enough to see the shadow of a submerged U-boat, the wake of a periscope, the oil slick of a wounded submarine.

Malta was becoming a technological testing ground. Those six sheds at Lazaretto represented the future of naval warfare. The Italian flying boats, the Japanese destroyers with their advanced engines, the British innovations – all of it centered on this small island. (Explore the Lazzaretto’s fascinating history)

But technology couldn’t stop the mines. On July 4, 1917, the sloops Aster and Azalea left Grand Harbour escorting the hospital ship Abbasieh. By 10:10am, Aster hit a mine eight nautical miles east of Malta. When Azalea moved to help, it hit another mine. Ten died on the Aster; the Azalea limped back to be beached at Marsaxlokk. The new technology of submarine warfare was winning against the old technology of surface escorts.

The hospital ship Goorkha hit a mine in October 1917, 15 miles northeast of Grand Harbour. It was carrying 345 patients and 17 nursing sisters. All were evacuated to another hospital ship, and the Goorkha survived, was towed back and repaired at the dockyard. But the message was clear: nowhere was safe. The submarines had turned the Mediterranean into a minefield.

On July 9, 1917, HMS Vanguard exploded at anchor in Scapa Flow, Scotland. Among the 843 dead were two Maltese: ward room messman Francisco Schembri and 3rd class cook Angelo Xuereb. Even serving far from home couldn’t guarantee safety.

This is why those kite balloons mattered. This is why every innovation counted. The war had become a race between detection and destruction.

The Human Cost of Empire

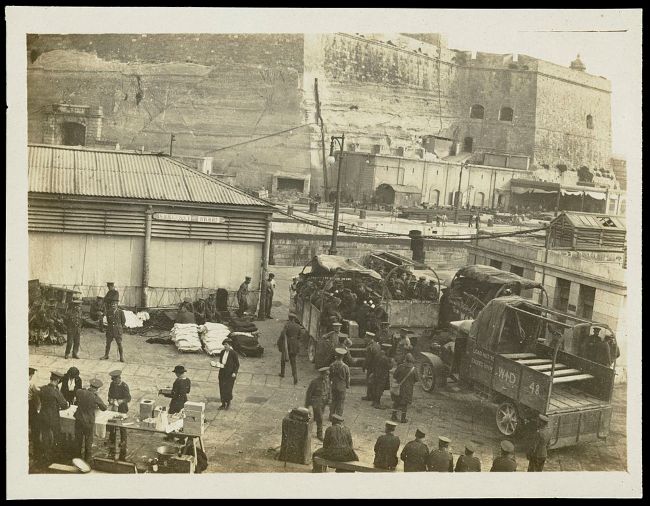

While technology advanced, humans paid the price. The Malta Labour Corps recruited 750 men in October 1917 – “chiefly coal heavers and farmers from Malta and Gozo.” The recruitment took place between October 13 and 16, 1917, with the battalion scheduled to leave on October 20. But transport shortages delayed departure until December 5.

Those waiting weeks, having already left their jobs in October, survived on sixpence a day retaining pay while their families dealt with profiteers and poisonous bread. The delay “caused financial hardship” – a bland official phrase that doesn’t capture the desperation of families who had lost their breadwinner’s wages while waiting for him to leave for a war zone.

The 2nd Battalion finally embarked on December 5, 1917, heading for Salonika (modern-day Thessaloniki in Greece). They joined the 1st Battalion, which had been there since September 1916, building infrastructure for the British Salonika Army’s fight against Bulgarian, German, and Austrian forces on the Macedonian Front. (Read about Malta’s role in other sieges)

Some never came home. On April 5, 1917, No 2256 Labourer G Dimech was killed and No 2221 Labourer D Caruana was wounded in an air raid at Karasouli. Gunner Angelo Mangion died trying to save sailors from the freighter Islandia when it ran aground at Delimara Point in December 1917. These weren’t warriors but workers, killed building the infrastructure of other people’s wars.

The Maltese labourers built two deep-water piers near the Standard Oil Depot at Salonika – Malta Pier and Pinto Pier, named for their homeland. About 100 men worked on the Decauville Railway. Others loaded and unloaded stores for the Royal Engineers. After the war ended in November 1918, some employment companies moved to Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Black Sea region. One unit remained there until at least May 1920, possibly near the Russian border.

Over 5,000 Maltese served in the Labour Corps during the war. In the course of their service, 124 members died – at least one killed in action, many others falling to the Spanish Flu pandemic that swept through military camps in 1918.

The Perfect Storm

By December 1917, Malta faced a perfect storm. Submarines made food imports dangerous. The best bread went to feed the military – not just British forces, but Japanese, French, and Italian allies too. Local profiteers squeezed what they could from scarcity.

The island’s role as the “Nurse of the Mediterranean” was ending. Since 1915, Malta’s hospitals had treated wounded from Gallipoli and other fronts. But by April 1917, submarine attacks on hospital ships made evacuations to Malta too dangerous. Five general hospitals – Nos. 61, 62, 63, 64, and 65 – were relocated from Malta to Salonika on July 11, 1917. The island that had cared for the empire’s wounded could no longer safely receive them. (Discover more about Malta’s strategic importance)

And through it all, those kite balloons rose each dawn from Lazaretto Creek, observers scanning for periscopes while below them a population survived on determination and degraded bread.

What Really Matters

The Japanese Navy that helped protect Malta in 1917 would attack the island’s convoys in 1942. The Italian flying boats that hunted submarines from Marsaxlokk would drop bombs on the same harbour. The French left because of venereal disease but would return as allies again. (Read about Malta’s role in WWII)

Alliances shift. Technology advances. But some things remain constant: where there are people, there will be trade. Where there is scarcity, someone will profit. Where there is war, civilians suffer. And where there is suffering, humans find ways to survive.

Those kite balloons at Lazaretto Creek were marvels of innovation. But the real story of Malta in 1917 wasn’t in the sky – it was in the bread queues, the police courts, the families waiting for news from Salonika. It was in the eternal dance between authority and black market, between official rations and human need, between technological progress and timeless hunger.

Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Howard Vella Dunbar might receive honours serving with the British Heavy Artillery in Italy. Maltese Lieutenant Charles Muscat might win the Military Cross on the Western Front. But their families back home still faced the same “heavy unpalatable abomination” in their daily bread.

The next time you pass Manoel Island, remember those six sheds and their kite balloons. But remember too the unnamed letter writer who complained about poisonous bread and suggested cooperative stores. Both were forms of resistance. Both were ways of fighting back. Both were quintessentially Maltese responses to impossible circumstances. (Learn more about Maltese resilience through history)

In war, everyone watches the sky for enemy aircraft. But survival happens at ground level, one mouldy loaf at a time.

Related Articles:

- Traditional Boats of Malta – Explore the maritime heritage that kept Malta connected

- The French Invasion of Malta: A Turning Point – Another period when Malta faced foreign occupation

- From Corsairs to Collapse – How Malta’s naval economy evolved through the centuries