And what it can teach us about the AI transition

Updated February 2026

What this article is about: Malta has spent centuries navigating systems larger than itself—Ottoman trade networks, European power politics, now AI. The archives reveal how they did it. These lessons aren’t abstract. They’re specific, documented, and surprisingly applicable.

30-Second Summary

- Malta in the 1530s was officially hostile to the powers it depended on for survival.

- The solution: protocols so robust that trust became irrelevant—safe-conducts, bonds, guarantors, documentation.

- Five uncomfortable lessons emerge from the archives, none of which appear in typical history content.

- The core insight: You don’t need to trust a system to work with it safely. You need scope, enforcement, verification, and fallbacks.

- This applies directly to AI. The checklist at the end is designed to be used.

Method note: This article draws on notarised contracts and chancery registers from Malta’s archives, cross-referenced with published scholarship listed in References. These Malta history AI lessons are about scope, enforcement, verification, and fallbacks.

The Paradox in the Archives

Officially, Malta was in formal conflict with networks it still had to trade through. This is how they made cooperation enforceable without pretending agreement.

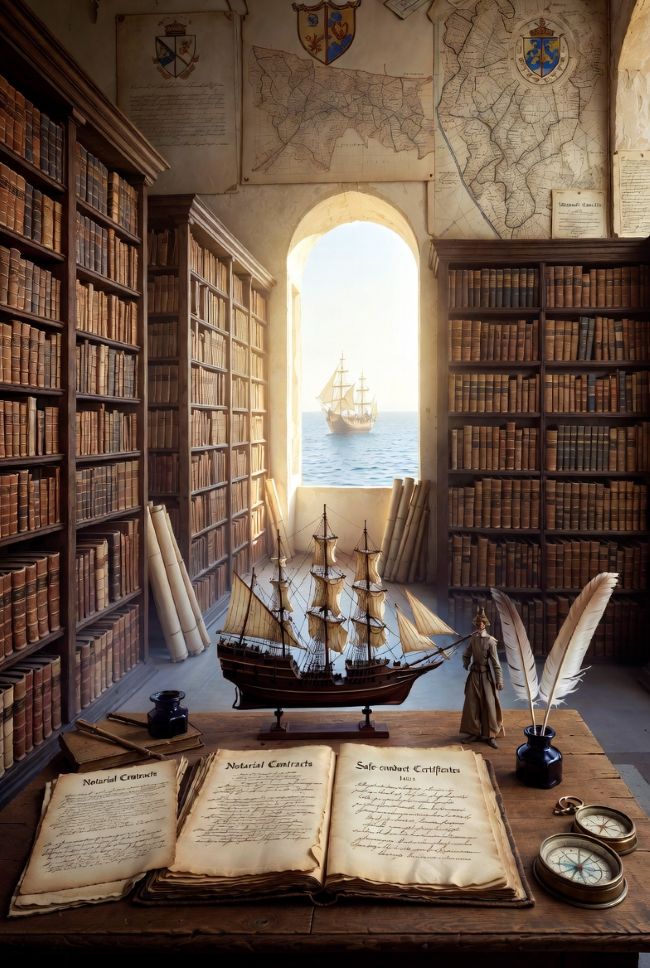

There’s a particular kind of document that survives in Malta’s Notarial Archives. Written in a Latin that borrows heavily from Sicilian and Arabic, these contracts record business partnerships, shipping arrangements, and financial agreements from the mid-1500s. They’re dry, procedural, and utterly fascinating—because they describe a world that officially shouldn’t have existed.

What can Malta history teach us? More than you’d expect—including lessons directly applicable to AI and other systems we depend on but don’t fully control. How Malta survived, and what those survival mechanisms reveal, is the subject of this article.

Malta in 1530 became the headquarters of the Knights of St John, a military religious order whose stated purpose was to defend Christendom against Ottoman expansion. The Knights had been expelled from Rhodes by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1522, and their new island base sat directly on the fault line between two civilisations locked in formal opposition.

And yet.

Buried in those notarial records are contracts for voyages to Tripoli. Safe-conduct certificates issued to merchants from Djerba. Partnership agreements for trading expeditions to what the documents carefully termed “lands beyond”—territories controlled by powers the Order formally opposed.

Key Insight: The archives preserve, in meticulous detail, a parallel reality where commerce quietly continued across supposedly impassable divides. This isn’t a story about tolerance or hypocrisy. It’s a story about systems—how they’re built, how they function under pressure, and what they reveal about the gap between official positions and operational necessities. The archival record shows cooperation without convergence: shared logistics, not shared values. This is not an argument for moral equivalence; it is a case study in operational safeguards.

The Paperwork of Pragmatism

Joan Abela, a historian who spent years in Malta’s Notarial Archives, uncovered the mechanics of how this worked. The contracts follow standard Mediterranean trading formats:

- Ship charters with cargo space allocated and delivery terms specified

- Payment schedules with penalties for delays—four gold scudi per day in one 1555 contract

- Weights and measures specified according to Messina standards

- Equipment requirements—ships must be “well-equipped” with proper tackle

These weren’t clandestine operations scratched on hidden papers. They were notarised agreements, legally binding, filed in official archives.

How Was This Possible?

The Knights needed supplies. Malta produced little. Sicily was the primary source, but it wasn’t always sufficient or affordable. North Africa had grain, leather, wool. The Levant had goods the Order required.

Economic necessity demanded what ideology forbade.

This tension sits at the heart of what historians call the island economy paradox—the structural reality that island nations must trade beyond their borders to survive, regardless of political or ideological constraints.

The solution was systematic. In October 1530, Pope Clement VII issued a decree permitting Malta’s new inhabitants to trade with merchants from the Barbary coast and Ottoman territories. The permission was framed around the island’s “precarious state of provisioning.”

Survival trumped doctrine—but it required official sanction to function.

Understanding the economics of the Knights of Malta reveals why this pragmatism was essential. The Order operated a sophisticated financial network spanning Europe, but local provisioning required local solutions.

The Safe-Conduct System: Malta’s Protocol for Working With Rivals

The most revealing documents are the safe-conduct certificates preserved in the Liber Bullarum, the registers of the Order’s Chancery. These were essentially passports issued by the Grand Master, guaranteeing that a named merchant could travel unmolested between Malta and specified ports.

Anatomy of a Safe-Conduct Certificate

| Element | Purpose | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Named merchant | Specific identification of protected party | Identity and access controls |

| Valid period | Typically one year; limited exposure | Contract terms / licence periods |

| Route specification | Defined scope of protection | Terms of service / usage limits |

| Grand Master’s seal | Binding authority on all Order vessels | Authoritative sign-off / governance approval |

| Enforcement clause | Penalties for violation | Liability frameworks |

A certificate from October 1555 grants passage to Hagi Buabdella de Chalipha, a trader from Tripoli. The language is formulaic but comprehensive: all captains and shipmasters are commanded, “in virtue of Holy Obedience,” to let him travel freely, “not permitting that he be molested, impeded or retarded in any way.”

The Enforcement Mechanism: Corsairs operating under Hospitaller licence were explicitly prohibited from attacking vessels carrying these safe-conducts. Licensed corsairs had to post bonds and provide guarantors who would be financially liable if they violated these restrictions. The system created accountability through economic incentive—not moral agreement.

This represented a sophisticated approach to medieval financial management—using economic instruments to enforce compliance where ideology alone could not.

The Intermediaries

Some individuals built entire careers in the space between these two worlds. The archives record North African merchants who had once been held captive in Malta, subsequently freed, and who then leveraged their knowledge of both societies to become commercial go-betweens.

Notable Intermediaries from the Archives

| Name | Background | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Mechamet de Africa | Originally from North Africa, later granted freedom | Safe-conduct to Tripoli for negotiations and trade |

| Murgian de Abdala | From Aden, freed during Grand Master election celebrations | Granted perpetual trading licence between homeland and Malta |

| Sydero Metaxi | Greek, employed on Order’s galleys | Procurement agent for wine from Zakinthos and Cefalonia |

These men understood something valuable: friction between systems creates opportunities for those who can navigate both. They weren’t neutral. They had loyalties, histories, grievances. But they had also developed a practical competence that made them useful to parties on each side.

The Order’s approach to managing these intermediaries reflected the medieval art of personnel management—recognising that human capital with cross-cultural competence was a strategic asset.

Meanwhile, spy reports from the period show that intelligence gathering often travelled the same channels as trade. The boundaries between commerce, diplomacy, and espionage were remarkably porous.

Why This Matters Now:

Maltese History give us Lessons on how to navigate the AI future

We are entering an era when a significant portion of economic, creative, administrative, and analytical work will be conducted by—or in partnership with—artificial intelligence systems. Not in some distant science-fiction future, but within the working lives of people reading this article.

In this article, “AI systems” means deployed tools and organisational workflows, not moral agents. The comparison is structural, not moral: mechanisms of safe cooperation under constraint.

The Numbers Are Already Here

| Projection | Source | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| 170 million new jobs created globally | World Economic Forum | By 2030 |

| 92 million jobs displaced | World Economic Forum | By 2030 |

| 59% of workers will need new skills | World Economic Forum | By 2030 |

Statistics current as of early 2026; projections subject to revision.

Takeaway: Churn is real. The advantage goes to people who can scope, verify, and govern AI-assisted work.

The parallel isn’t exact. History never is. But it’s close enough to be useful.

The Structural Similarity: The Knights faced a system they couldn’t ignore, couldn’t fully control, and couldn’t philosophically embrace. Ottoman commercial networks were more extensive, better capitalised, and controlled access to goods Malta needed. The Order’s official position was opposition. Its operational reality was interdependence.

We are approaching something structurally similar. AI systems are becoming embedded in supply chains, professional services, creative industries, financial markets, and administrative processes. Many people have legitimate concerns—opacity, employment effects, concentration of power. Those concerns will not make the systems go away.

For a deeper exploration of how historical thinking frameworks can help navigate technological disruption, see our series on mental models for the AI age.

Five Uncomfortable Lessons the Archives Reveal

These aren’t general observations. They’re specific patterns from the contracts, certificates, and registers—patterns that don’t appear in typical Malta history content. They describe mechanisms, not morals. These are governance patterns, not endorsements of any side.

1. Trust Is a Luxury. Protocol Is Infrastructure.

Every modern AI article says “we need to build trust in AI.” The Maltese archives say the opposite.

The Knights didn’t trust the merchants. The merchants didn’t trust the Knights. Nobody changed their mind about anything. What they built instead: documentation so tight that trust became irrelevant. The safe-conduct wasn’t a gesture of goodwill. It was a legal instrument with financial penalties attached.

Do not rely on trust as the primary control mechanism. Build protocols so robust that trust doesn’t matter. Define scope. Require logging. Attach consequences to violations. Trust is nice. Protocol is what works when trust fails.

2. The Displaced Become the Bridge.

Mechamet de Africa started on the wrong side of the power dynamic. Then he was freed. Then he became one of the most valuable commercial intermediaries in the Mediterranean.

Why? Because he understood both systems from the inside. He knew how Maltese institutions worked. He knew how North African trading networks operated. That double knowledge made him indispensable.

The pattern repeats throughout the archives: Murgian de Abdala, freed during celebrations, granted perpetual trading rights. Sydero Metaxi, employed on the galleys, became the Order’s trusted procurement agent. Disruption created competence.

The people most affected by AI today—writers, analysts, researchers, administrators—may become the most valuable translators tomorrow. Not despite their experience of disruption, but because of it. They understand what’s being lost. They can see both sides.

3. Public Opposition, Private Protocol.

Here’s a detail that doesn’t make it into the tourist brochures.

The Grand Master personally signed safe-conducts for merchants from ports the Order officially opposed. Not delegated to a subordinate. Signed himself. The wax seal of the highest authority in Malta, affixed to documents enabling commerce across formal divides.

The institution maintained rhetorical distance while building bureaucratic cooperation. The public position and the operational reality were different—and everyone involved understood this.

What this means now: You don’t have to publicly embrace AI to privately systematise it. Many organisations are doing exactly this—cautious in meetings, integrated in operations. That’s not hypocrisy. That’s how institutions have always adapted to systems they can’t ignore.

4. Small Islands Don’t Choose Their Dependencies—Only Their Terms.

Malta couldn’t opt out of Mediterranean power dynamics. The island produced almost nothing it needed. It sat on trade routes it didn’t control. It depended on systems larger than itself—Sicilian grain, North African leather, Levantine goods.

The question was never “should we engage?” That wasn’t a choice. The question was “under what terms?”

Same applies now. In many sectors, opting out of AI will be difficult. The systems are already embedded in supply chains, tools, and competitors’ operations. The real question is: what are your terms? What do you log? What do you verify? What do you refuse?

Those are the choices that actually matter.

5. Enforcement Was Internal, Not External.

When a corsair violated a safe-conduct, who punished him?

Not a distant court. Not the other side. His own guarantors—other Maltese—paid the bond. The system made each side police its own.

The contracts specify this clearly: named guarantors, specified sums, financial liability for violations. The enforcement mechanism wasn’t “we’ll catch you.” It was “your own people will pay.”

AI accountability will work the same way. Regulators won’t catch everything. They can’t move fast enough. The real enforcement will be internal—your own audit trails, your own verification habits, your own fallback plans, your own professional reputation when something goes wrong.

Applying the Lessons: A Practical Framework

The revelations above are insights. This section is implementation.

The AI Safe-Conduct Checklist

Before integrating any AI system into consequential work, answer these questions:

| Element | Question to Answer |

|---|---|

| Scope | What data goes in, what comes out, what is forbidden? |

| Identity | Who is allowed to use it (accounts, roles, approvals)? |

| Logging | What is recorded (inputs, outputs, decisions, reviewer)? |

| Verification | What must be checked by a human, and how? |

| Liability | Who owns mistakes and how are incidents handled? |

| Fallback | What happens if the AI tool is unavailable or wrong? |

The CAF (Consider All Factors) thinking tool offers a systematic approach to evaluating such decisions before commitment.

Building Your Intermediary Skills

If you want to position yourself as someone who bridges human and AI systems:

- Interpretation—translating AI outputs into human contexts

- Judgment—knowing when AI recommendations apply and when they don’t

- Accountability—maintaining audit trails and responsibility chains

- Relationship management—the human connections that AI cannot replicate

The OPV (Other People’s Views) framework helps here—understanding how different stakeholders perceive AI integration lets you bridge perspectives effectively.

Your Verification Habits

Develop these now, before you need them:

- Cross-reference AI-generated information with primary sources

- Maintain independent knowledge in areas that matter to you

- Test outputs before deploying them in consequential contexts

- Document verification steps for later accountability

The C&S (Consequences and Sequels) thinking tool helps map out downstream effects across different time horizons.

Practical Takeaways: A Summary

The Pattern That Has Worked for Centuries

| What Malta Did | What You Can Do |

|---|---|

| Safe-conduct certificates with defined scope | Define exactly what AI can access and produce |

| Bonds and guarantors—your own people paid for violations | Make accountability internal, not dependent on regulators |

| Intermediaries who understood both sides | Build skills that bridge human judgment and AI capability |

| Independent price verification before committing | Never deploy AI outputs in consequential contexts without checking |

| Official sanction for necessary pragmatism | Document your AI use policies before you need to defend them |

| Everything notarised and filed | Log inputs, outputs, decisions, and who reviewed them |

Living in the Transition

Malta is still a small island dependent on systems larger than itself, international finance, global tourism, digital infrastructure. The structural constraint hasn’t changed in centuries. What worked then still applies.

The Grand Masters who signed safe-conducts weren’t abandoning their principles. They were maintaining operational capacity in a complex environment. The merchants who applied for those certificates weren’t endorsing the Order’s worldview. They were securing conditions for viable commerce.

Neither side pretended the underlying tensions had disappeared. Neither expected fundamental conflicts of interest to resolve themselves. They built systems that worked anyway—documented, enforceable, with clear accountability.

That’s the pattern. It’s not inspiring. It’s not a vision of harmony. It’s a survival mechanism refined over centuries by people who couldn’t afford to get it wrong.

The Durable Lesson: Functioning relationships don’t require resolution of fundamental differences. They require protocols, documentation, intermediaries with cross-system knowledge, and mechanisms that account for self-interest rather than assuming it away.

In many sectors, opting out of AI will be difficult. Malta couldn’t opt out of the Mediterranean. The question was never whether to engage—it was whether to set terms or have terms set for you.

That’s what the archives teach.

Explore Further

For more on the Knights of Malta:

- The Economics of the Knights of Malta

- How the Knights Mastered Medieval Wealth

- 10 Mind-Blowing Facts About the Knights of Malta

- Fort St Angelo: A Historical and Cultural Icon

For thinking frameworks relevant to navigating change:

- Mental Models for the AI Age

- Edward de Bono’s Malta Thinking Legacy

- PMI: Plus, Minus, Interesting

- Six Thinking Hats: Parallel Thinking

For historical context:

- The Ottoman Empire’s Rise and the Great Siege

- Strategic Lessons from the Ottoman Raid of 1644

- Traditional Boats of Malta

Frequently Asked Questions

What were safe-conduct certificates in 16th-century Malta? Safe-conduct certificates were official documents issued by the Grand Master of the Knights of St John, guaranteeing that a named merchant could travel and trade unmolested between Malta and specified ports. They were valid for fixed periods, typically one year, and were enforceable through financial bonds.

Why did the Knights of St John allow trade with rival ports? Malta produced little food or raw materials. Economic survival required trade beyond the island’s borders, including with ports controlled by powers the Order formally opposed. Pope Clement VII granted permission in 1530, framing it around the island’s “precarious state of provisioning.”

What is the modern equivalent of safe-conduct in AI workflows? The modern equivalent is a combination of access controls, scoped permissions, logging, and liability frameworks. Just as safe-conduct certificates defined who could trade, what routes were permitted, and what penalties applied for violations, AI governance requires similar clarity on scope, identity, verification, and accountability.

How do I verify AI outputs in high-stakes work? Cross-reference AI-generated information with primary sources. Maintain independent knowledge in areas that matter to you. Test outputs before deploying them in consequential contexts. Document verification steps for later accountability.

Do I need to trust AI to use it safely? No. The historical lesson from Malta is that functioning cooperation does not require shared values or trust. It requires protocols, documentation, verification, and mechanisms that account for self-interest. Treat AI as a powerful workflow tool, not a trusted colleague.

What should I log when I use AI at work? Log inputs (what you asked), outputs (what the AI produced), decisions (what you did with it), and reviewer identity (who checked it). This creates an audit trail for accountability and helps identify patterns when things go wrong.

References

Primary Historical Sources

Notarial Archives Valletta (NAV): Registers 202/1, 202/8, 224/1, 225/17; MS 514/1, MS 778/1

National Library of Malta, Archives of the Order of Malta (AOM): Liber Bullarum MS 414, 415, 423, 425, 427

Historical Scholarship

Abela, Joan. “A Window on Muslim Traders in the Mediterranean through Maltese Archives (1530-1565).” In Seapower, Technology and Trade: Studies in Turkish Maritime History, edited by Dejanirah Couto, Feza Günergun, and Maria Pia Pedani, 264-274. Istanbul: Denizler Kitabevi, 2014.

Abela, Joan. Port Activities in Mid-Sixteenth Century Malta. MA Dissertation, University of Malta, 2007.

Brogini, Anne. Malte, frontière de chrétienté (1530-1670). Rome: École française de Rome, 2006.

Brogini, Anne. “Relations between France and Malta in the Early Modern Period.” In Malta and France: Shared Histories, New Visions, edited by Elaine Falzon, Alexander Debono, and Charles Xuereb, 20-34. Malta: Ambassade de France à Malte, 2023.

Braudel, Fernand. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Translated by Siân Reynolds. 2 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Greene, Molly. Catholic Pirates and Greek Merchants: A Maritime History of the Early Modern Mediterranean. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Kaiser, Wolfgang. “L’économie de la rançon en Méditerranée occidentale (XVIe-XVIIe siècle).” In Richezza del mare, Richezza dal mare, secc. XIII-XVIII, edited by S. Cavaciocchi, vol. 2, 689-701. Florence: Le Monnier, 2006.

Paoli, Sebastiano. Codice Diplomatico del Sacro Militare Ordine Gerosolimitano, oggi di Malta. 2 vols. Lucca: Salvatore e Giandomenico Marescandoli, 1737.

AI and Future of Work

International Monetary Fund. “New Skills and AI Are Reshaping the Future of Work.” IMF Blog, January 2026.

McKinsey Global Institute. “AI: Work Partnerships Between People, Agents, and Robots.” McKinsey & Company, November 2025.

PwC. “Global AI Jobs Barometer.” PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2025.

World Economic Forum. “Four Futures for Jobs in the New Economy: AI and Talent in 2030.” Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2025.

World Economic Forum. “Future of Jobs Report 2025.” Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2025.