DISCLAIMER

This is a work of fiction. While it incorporates historical events, all characters, conversations, and supernatural elements are fictional. Any resemblance to real persons beyond general historical context is coincidental. Historical liberties have been taken for narrative purposes. Future chapters are speculative fiction only. All rights reserved ManicMalta.com. This book cannot be reproduced in part or in full, copied or printed.

She was laughing.

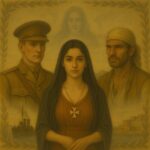

Maria Borg stepped out of the Rozina Cumbo Hospital after her morning shift. Named for the legendary healer who had tended the wounded during the Great Siege, the small hospital stood as a testament to resilience in Birkirkara. Maria had been tending to children with fever through the night. Now, in the gentle morning light, she paused to watch two girls playing hopscotch in the square.

They waved to her, recognizing the nurse who had helped deliver many of the village’s children. She waved back, walking toward them. The chalk lines of their game crisscrossed the dusty square. A boy clapped, waiting his turn. It was morning, and Birkirkara still pretended that nothing had changed. A dangerous illusion.

Then the shot.

Not aimed. Not planned.

A French soldier—young, afraid, maybe just startled—fired.

The echo silenced everything.

Maria folded mid-step. The girls screamed. The boy ran.

A silver pendant she wore—a gift from her husband—snapped from her neck and fell beside her.

No cannon. No battlefield. Just children. And blood.

From the alley, Vincenzo Borg ran too late. He dropped to his knees. His wife—his world—gone.

And I felt it too. Beneath the earth. A soft bloom of heat in the limestone.

I had watched a thousand storms pass over these islands, and a thousand armies. But none like this. None that carried ideals, and looting, in the same breath.

Marble falls to dust Liberty breeds betrayal Blood stains limestone streets

NAPOLEON ARRIVES

They arrived on June 9, 1798, on tall ships with tri-coloured flags and mouths full of liberty. Napoleon Bonaparte himself, the young general whose campaigns had already reshaped Europe, landed with a force of 29,000 men against Malta’s meager defense of 332 Knights and few thousand local soldiers.

Scientists. Scholars. Soldiers. Clerks. Frenchmen all. And Malta fell to them.

The Knights of St. John, who had ruled for 268 years, surrendered with barely a struggle, their Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch failing to mount any meaningful resistance. Many suspected secret arrangements had been made—betrayal from within the Order itself.

I had seen the Knights arrive centuries ago as fierce warriors. I watched them leave as comfortable aristocrats, their fighting spirit long since dulled by luxury.

Bonaparte wasted no time. With characteristic efficiency, he reorganized Malta’s governance in about ten days before departing for his Egyptian campaign on June 19, leaving General Claude-Henri Vaubois with 4,000 men to maintain French control. Malta’s strategic position in the Mediterranean made it invaluable—a crucial naval base bridging France and Egypt, a stepping stone for Napoleon’s greater ambitions in the East.

They came promising enlightenment, but was Malta ready for these new ways of thinking?

They abolished slavery and nobility titles. Opened schools for both boys and girls. Reformed the university. Created a system of primary education available to all. Established freedom of the press and civil marriages. Divided the islands into administrative cantons modeled after the French system.

The Church was a power to be reckoned with in Malta, stepping on it’s toes was the fatal mistake of the French. I watched as powers jawed for control manipulating the minds of my people, who tended my soil and fished in my waters.

They also emptied churches. Auctioned chalices. Confiscated the property of religious orders. Closed numerous monasteries and convents. Banned church bells and processions. Melted down gold and silver liturgical items to fund their military campaigns. The French troops even tore down tapestries in the Magisterial Palace to extract the silver and gold thread woven into them.

Some Maltese cheered for these revolutionary changes. Others clenched their fists at the violation of their sacred traditions.

Most feared, the churches threats of eternal fire in the depths of hell if they sided with the devil. I watched as society, cracked with confusion.

But as the French negotiated the final terms with the Knights of St. John, I felt it—violence coming not from foreign boots alone, but from within. Brother against brother. Villager against neighbour. The hard-won unity of the Great Siege began to crumble.

And something in me recoiled.

I had known conquest. I had not known betrayal.

THE EARTH TREMBLES

The afternoon of June 11, 1798, brought thick air and tense silence to Valletta. Inside the Grand Master’s Palace, French officers and General Bonaparte’s representatives sat across from Grand Master Hompesch and the Knights of St. John. The formal surrender was being concluded—a process that had begun two days earlier when Bonaparte’s forces landed at Marsaxlokk Bay.

Suddenly, at precisely three o’clock, the room shook. Ink spilled across parchment. Chairs scraped backward. Men caught their balance against walls and tables.

An earthquake—brief but unmistakable—passed through Malta.

I felt the island itself shudder in protest. The limestone beds that had witnessed seven thousand years of history seemed to recoil at this latest exchange of masters. Not my doing—the earth has its own voice—but a tremor that echoed my own disquiet.

The timing felt like more than coincidence. As though Malta itself rebelled against the signatures flowing across the page.

The French general’s aide crossed himself discreetly. A Maltese servant whispered, “A sign.” Grand Master Hompesch, pale and defeated, adjusted his collar and continued as though nothing had happened.

Within me, something had changed since that night years ago when lightning found me during the Great Siege. The energy had settled into my being, transforming what I was, expanding what I might become. Though I did not cause the earth to move, I felt it differently now—a vibration that resonated with my intuition.

A clerk swore under his breath.

“Earthquake,” someone muttered.

“A warning,” whispered another.

Stone cracks in silence The ground does not pick a side Only echoes pain

When it was over, Malta belonged to the French. But only for a moment.

In Birkirkara, Vincenzo Borg stood by the body of his wife. Shot during the landing. An accident, they said. Collateral.

He did not cry. He did not shout.

He closed her eyes, his touch gentle as if she were merely sleeping.

And then he opened his own.

Across the village square, Matthew Pulis stepped forward. Merchant. Smuggler. A man who had traded in foreign ports and returned with ideas more dangerous than weapons—ideas about liberty, about self-rule. He had seen revolutions rise and fall across the sea.

“How many more must die before we act?” he asked.

Borg looked past him, toward the church where the tricolour now flew.

“We have no cannons,” he said.

“But we know every path. Every cave. Every heart that still beats for Malta.” Pulis’s eyes gleamed with the spirit of the Great Siege, the memory of past defiance. “We have the blood of those who stood against the Ottomans.”

Borg hesitated, then slipped Maria’s silver pendant from his pocket. He’d retrieved it from where it had fallen beside her body. The chain was broken, but the small Maltese cross still gleamed in the fading light. He clutched it tightly.

“She always said churches were the safest places in times of trouble,” Borg said quietly. “Yet they target even those now.”

Pulis nodded grimly. “Which is why they won’t expect us to use them. The French avoid firing on churches when possible—it turns too many against them. We could meet there, right under their noses.”

“A dangerous gamble.”

“This whole island is a dangerous gamble now.”

Liberty wears masks Sometimes velvet, sometimes steel Sometimes both at once

Within days, resistance bloomed. Farmers with pitchforks. Sailors with knives. Priests hiding weapons beneath altars. The island rose not as an army—but as a body. Every limb twitching, unsure, angry, alive.

They organized into what would later be called the National Assembly. Merchants. Clergy. Notaries. Men who had witnessed the Corsican struggle against French rule and heard tales of the American colonies’ independence. Men who now saw their chance to claim something of their own destiny.

Vincenzo Borg became known as “Brared.” Leader of the Birkirkara battalion. His headquarters: the Ta’ Xindi Farmhouse.

They moved like roots underground. Quiet. Slow. Determined.

The French never saw it coming.

One morning, scouts brought word: four French cannons were being moved toward Mriehel. Heavily guarded. Intended to control the central villages.

Borg marked the route with his thumb on the map. “If they get through, we lose this war.”

“Then they don’t,” Pulis said.

Limestone in their hands

No musket, no polished sword

Malta rises up

THE BATTLE OF MRIEHEL

Dawn broke gold over Birkirkara. The air tasted of dust and promise. Vincenzo Borg crouched behind a low wall, watching the approaching French column. Four cannons. Twenty soldiers. One lieutenant on horseback, his uniform immaculate in the morning light.

Behind Borg, thirty men waited. Farmers. Stonemasons. A blacksmith who had once shaped horseshoes, now molding bullets from church bell fragments.

“Remember,” Borg whispered. “The cannons. Not the men. Disable those cannons. If we let them fire, it’s over. They will get most of us.”

A young apprentice stonemason nodded nervously making the sign of the cross. His hands—already calloused from years of working with limestone—gripped an old tool repurposed as a weapon.

I felt them above me. The weight of their footsteps. The press of their fear against my limestone. And something else—determination like I had never tasted before. Their fear called me. I flickered with energy, I could feel the resonance within me oscillating at a rapid pace. I had no feelings, but I knew right and wrong when I saw it.

The French lieutenant rode easily, confident. His men’s boots scraped limestone. The cannons groaned forward, wheels protesting against the uneven ground.

Then—a donkey brayed.

The signal.

From rooftops. From wells. From under carts. The Maltese erupted.

The lieutenant laughed, gesturing dismissively at what appeared to be an unorganized mob. “Form defensive positions!” he called to his men, his voice calm and measured. “Prepare the cannons!”

He was not afraid. Four field cannons were more than enough to obliterate this ragtag group of peasants. He forgot who was home, and who was not.

“Form square! Artillery to the center!” the lieutenant called out, his voice carrying the confidence of professional training. “First and Fourth positions, prepare to engage!”

The infantry soldiers quickly arranged themselves defensively while the cannon crews sprang into action with disciplined precision.

I had not meant to interfere. To cross the line from observer to participant. But as the French prepared to unleash devastation on my people, something stirred within me—that same energy that had entered me during the Great Siege when lightning found me.

And I reached out.

“Load grape!” the lieutenant ordered, watching as his trained gunners moved through their well-rehearsed routine.

Each crew worked in coordinated motion—one man stepped forward with the worming tool to clear the barrel, another brought forward the powder charge, while a third try to prepare the grape shot canister, filled with deadly lead balls designed to scatter like lethal hail.

“What’s this?” one gunner muttered, struggling to separate two canisters that had mysteriously stuck together.

The lightning that had changed me years ago had left something behind—an affinity for metals, especially iron, for the magnetic fields that coursed invisibly through the world. I didn’t understand it myself. But as I concentrated on the iron cannonballs, I felt them respond—just slightly, just enough.

In the mean time, the powder was rammed home but without the grape canister, the canon was useless. Soldiers confused now, their mechanical efficiency born from countless drills interrupted.

“The canisters are acting strange, sir,” another called to the lieutenant.

“Sir, the canisters won’t seperate” a third gunner called out in frustration as two man struggled trying to seperate the cannisters.

The lieutenant’s confidence faltered as all four cannon crews struggled with the inexplicably misbehaving iron. “What is happening?” he shouted, drawing his sword. “Load them properly, now!”

The delay I created had given Borg’s men their chance. They swarmed the column from all sides. Not with military precision, but with the intimate knowledge of those who had climbed these walls as children. Who knew which stones wobbled. Which alleys led nowhere. Which roofs would hold weight.

A French cannoneer raised his ramrod like a club. The young stonemason dodged the blow, and in the chaos that followed, the Frenchman fell. The apprentice stood frozen, witnessing death at close quarters for the first time.

I felt his shock. The sudden understanding of what battle truly meant. And for a moment, I reached toward him—moving his scythe up in the air, giving him enough courage, to stop a French soldier aiming his musket at Borg. Blood.

As the battle raged, the lieutenant found his sword oddly difficult to control—the blade seemed to pull slightly toward the metal components. For a crucial moment, his swing went wide, leaving him vulnerable.

I had never exercised such influence before. This subtle effect on iron. It left me drained, confused at my own capabilities.

“Take it!” Borg shouted.

Six men swarmed the nearest cannon. Hands that had pulled fishing nets now fought for iron. The French gunners died defending their charge. The Maltese died taking it.

Blood ran in rivulets between limestone pavers, seeking lowest ground. Seeping into the porous rock beneath. Soaking into me.

When it ended, the cannons remained. So did nineteen bodies. So did the story.

Borg stood panting, a cut across his cheek streaming red into his beard. Pulis wiped a French officer’s sword against his thigh, claiming it with a nod.

Borg studied one of the cannons, running his hand along the barrel that should have unleashed death upon them. The metal felt ordinary now, but he had seen the strange behavior of the iron during the battle—how the cannonballs had seemed to resist the French gunners’ efforts.

“The stones themselves fought for Malta today,” he said quietly. “As they did during the Great Siege.”

They spoke of divine intervention after the battle. They claimed celestial protection guided them, that the very elements had conspired against the French weapons.

They created stories to explain what they could not understand.

Lightning had changed me. The energy of storms now resided within me, allowing me to do more than merely witness. The universe perhaps never intended this evolution, this crossing from observation to subtle action.

How could I remain passive, sensing my lands turned red?

A silent guardian, curled beneath the stone, mourning what I could not prevent. Breathing in lightning. Exhaling sorrow.

I am not a god Not a saint, not salvation Only memory

And Malta remembers.

Even as it tears itself apart.

THE FRACTURING

Across Malta, violence erupted—not just between French and Maltese, but between Maltese and Maltese. The bloodshed was staggering—twelve thousand Maltese killed by their own countrymen during this civil war, their blood seeping into my limestone far more abundantly than during the Great Siege centuries before. Some had taken work with the occupiers. Others led resistance. Words turned into fists. Then knives. Then guns. And suddenly, there were no uniforms, just blood on limestone.

I had never seen this before.

I had seen enemies arrive by sea. But never sons of Malta strike each other in such numbers, with such rage. Not even during the darkest days of the Great Siege had the island turned against itself with such fury.

This was the true fracture.

The tavern in Żebbuġ fell silent as Lorenz Mifsud confronted his cousin Paolo across the room. Their shadows stretched long across the walls, twisted by candlelight. Two men who had once shared childhood games, now facing each other like strangers.

“Collaborator,” Lorenz accused, his voice thick with drink and grief. “My brother is dead while you count French coins.”

Paolo remained calm. “I translate documents. I don’t fire guns.”

“You give them our language. Our secrets.”

“I feed my children. Would yours rather have a dead hero for a father?”

The argument escalated. Others joined in, taking sides. The divisions that ran through all of Malta were reflected in this one room—pragmatists versus idealists, those who adapted versus those who resisted, families torn apart by impossible choices.

An old man tried to intervene—someone who remembered when both were boys picking carobs together. He was pushed aside as tempers flared.

“Enough!” The voice cut through the tension—Vincenzo Borg stood in the doorway, his presence filling the small space. “Is this what we’ve become? Maltese blood spilled by Maltese hands?”

The knife wavered. Lowered.

“Save your blade for the French,” Borg said quietly to Lorenz. Then, to Paolo: “And you. There are ways to feed your children without bending your knee. Come to Ta’ Xindi tomorrow. We need translators too.”

As Paolo moved to leave, Borg caught his arm and whispered, “The French—are they watching the churches in Senglea?”

Paolo hesitated. “Not closely. They consider them harmless. They’re more concerned with the harbor approaches by the sea.”

“Good,” Borg murmured. “Remember that.”

As the men separated, tension bleeding slowly from the room, I felt the true cost of occupation. Not just in lives lost, but in trust broken. In families divided. In a thousand tiny choices that left scars deeper than cannons ever could.

This was what Napoleon had truly brought to Malta. Not just a new flag, but a mirror in which my people saw themselves differently. Some as patriots. Some as pragmatists. Some as betrayers. The lines shifting like sand with each French decree, each church looted, each small kindness or cruelty from the occupiers.

THE RISING

In Valletta, the situation worsened rapidly. On September 2, 1798, less than three months after the French arrival, the breaking point came when French soldiers attempted to loot the Carmelite Church in Mdina and the Church of St. Nicholas in Siggiewi. The Maltese citizens, already resentful of attacks on their religion, rose up and killed the looters. The French had gravely miscalculated—in this deeply Catholic society, the seizure of church treasures and suppression of religious practices were intolerable provocations.

Food supplies were already strained. When the rebellion began, the French troops retreated into the fortified cities around Grand Harbour, taking control of Valletta and the Three Cities. The British Royal Navy, seeing an opportunity to weaken their French enemies, established a blockade that would last for two years. As months passed, conditions within the French-controlled areas deteriorated severely—food became scarce, disease spread, and both the French garrison and Maltese civilians trapped within suffered greatly.

Canon Francesco Saverio Caruana, rector of the University, emerged as one of the rebellion’s intellectual leaders. Alexander Ball, captain of the British HMS Alexander, made contact with the Maltese insurgents, promising British support against the French. Ball soon became a familiar figure in the villages, the King of Naples lending his authority to the Maltese cause through him.

In Valletta, French General Vaubois found himself besieged by the very people he had come to “liberate.” His proclamations grew increasingly desperate as food dwindled. The four thousand French troops, initially welcomed by some as enlightened reformers, now found themselves prisoners in the very fortifications built by the Knights they had displaced.

Borg’s resistance spread like fire across dry fields. Villages that had once quarreled now passed messages in bread loaves, in the arrangement of laundry, in children’s songs that carried coded warnings.

Every household had a task. Every person a role.

A widow in Żurrieq who had never left her village mixed powders that could blind or burn. A carpenter in Siġġiewi crafted false-bottomed carts that carried weapons beneath vegetables. Children too young to write their names became messengers, their innocence their greatest protection.

In Birkirkara, a young man named Tumas kept watch from his father’s rooftop, a stolen French spyglass helping him count soldiers, chart movements, note weaknesses. Before the French came, he had planned to become a carpenter. Now he mapped troop movements with careful precision.

The Portuguese Knight Fra Major Joachim Navarro de Andrade, who had remained in Malta, worked closely with Borg to organize the insurgents into an effective fighting force. Together, they developed a system of rotating meeting locations—a different church each week, gatherings disguised as prayer services. The French, despite their anti-clerical policies, remained hesitant to attack worshippers directly. It was the perfect cover.

I watched them all. These ordinary people becoming extraordinary under pressure. These peaceable souls learning war not from drill sergeants but from necessity.

And I stayed near.

And I stayed near.

Not as actively as during the Battle of Mriehel, but present. A subtle pull on a French soldier’s musket that caused his shot to miss. A strange attraction between metal buttons on a sentry to warn him of an incoming patrol. A compass needle that inexplicably pointed toward in the wrong direction, leading the French in the wrong direction.

Small things. Quiet things. But all involving metal and magnetism—the only forces I could influence since the lightning changed me.

I watched them all. These ordinary people becoming extraordinary under pressure. These peaceable souls learning war not from drill sergeants but from necessity.

Divine or guardian Bomb that fails to explode Faith finds its answer

THE MIRACLE AT SENGLEA

Dawn broke cold on February 6, 1799. A harsh winter wind swept across Grand Harbour, carrying the scent of gunpowder and hunger. In Senglea, church bells remained silent—banned by French decree—but people gathered nonetheless, slipping through narrow streets toward the parish church.

This was no ordinary Mass. Inside, beneath the painted vault of the ceiling, Vincenzo Borg met with Emanuel Vitale and Canon Caruana. Leaders of the three main fronts of Maltese resistance, they had risked everything to gather here, along with a dozen captains from various villages. Protected by lookouts posted at the street corners, they bent over rough maps spread across the altar.

“The French ammunition stores in Vittoriosa,” Borg traced the location with his finger. “If we strike there, their artillery falls silent.”

“Too well guarded,” Vitale argued. “We would lose too many men.”

“Then we need information.” Borg looked at Caruana. “Your university contacts inside Valletta—”

A boy—no more than twelve—burst through the side door, breathless. “French patrol!” he gasped. “Twenty men, moving this way!”

The maps disappeared into cassocks and under shirts. Weapons were concealed. The resistance leaders and their captains moved to blend with the ordinary worshippers now entering for the morning service. Borg slipped to a pew near the back, fingering Maria’s silver pendant that he kept always in his pocket.

I sensed it before they did. A spiteful intention. A target marked.

Something more than a random patrol.

In a room overlooking the harbor, a French officer handed a spyglass to General Vaubois.

“You’re certain they’re all there? Borg? Vitale? Caruana?”

“Yes, General. Our informant confirmed it. They’ve grown overconfident, using the churches for their meetings.”

Vaubois smiled thinly. “Then let us answer their prayers. Prepare the special ordnance.”

Inside the church, the priest lifted his hands. Children fidgeted. A mother whispered a prayer. Borg exchanged glances with Vitale across the aisle, a subtle nod confirming that the French patrol had passed by.

And then—a sound not unlike thunder, though there were no clouds. A whistling. A shriek.

The four 1.5kg steel fragmentation grenades through glass, trailing sparks like some furious comet.

It struck the church terrace. The stone blackened. The air scorched. Fire rays burst outward—brilliant, terrifying—then silence.

No explosion.

No death.

Only smoke like a dragon’s breath.

Some dropped to their knees.

Some ran.

They called it divine protection.

But I had felt it as it fell. Felt the twist in the sky, the metal streaking downward. And I had reached for it—not with hands, but with what I had become.

A field. A frequency. A flicker of charge across limestone.

I caught its breath before it opened.

Not miracle. Not magic. Not divine intervention.

Just me.

And him—Vincenzo Borg—whose grief had first drawn me closer to the surface than I had been in centuries. His wife’s death had awakened something in me. A responsibility I had not recognized until now.

Father Baldacchino approached one of the four grenades cautiously, his cassock fluttering in the morning breeze. Around him, parishioners whispered prayers, some still kneeling, others pointing toward the blackened stone where the bomb had landed.

“Don’t touch it, Father!” someone called.

But the priest moved forward anyway, compelled by something he could not name. The bomb lay split open, its casing cracked like an egg. But instead of destruction, it had released only heat and light—like lightning captured in metal.

“A miracle,” he murmured, making the sign of the cross.

Inside the church, the resistance leaders exchanged looks of wonder and determination. Their meeting had been known. They had been targeted specifically. Yet they had been spared.

“God is with us,” Caruana whispered.

Borg said nothing, but clutched the silver pendant that had been his wife’s, feeling a strange warmth radiating from the metal that shouldn’t have been possible in the cold February air.

Some one threw two grenades and threw them back to the patrol. They ran.

Later, French soldiers came to retrieve the grenades. They studied it with scientific curiosity, argued in technical terms about fuses and powder composition. They took measurements, made notes, carried away fragments for analysis.

But they could not explain what had happened.

Nor could I, fully.

I had reached without thinking. Had touched the bomb’s heart with something like hands, something like thought, something like the energy that lightning had left inside me.

And somehow, the explosion turned inward instead of outward. The fire consumed itself rather than the church and its people.

I did not claim credit. I did not want it.

But I felt a quiet satisfaction that night, as I rested deep beneath Malta’s surface. A sense that perhaps my changing nature served some purpose after all.

Victory's shadow Twelve thousand graves in silence Freedom's heavy price

THE COST OF LIBERATION

The French occupation lasted just over two years, from June 1798 to September 1800. Two years of blockade. Of hunger. Of resistance. Of Maltese blood on Maltese hands.

The siege of Valletta was a brutal affair. Inside the fortified city, the French troops and Maltese who had allied with them faced starvation as supplies dwindled. Disease spread through cramped quarters. The blockade’s economic impact devastated even those outside French-controlled areas, as maritime trade—the lifeblood of the island economy—ground to a halt. Farmers could not export their produce, artisans lost foreign markets, and imports of grain and other essentials became precious commodities.

In the countryside, Maltese battalions became increasingly organized, developing into a proto-national army. Emanuel Vitale commanded in the south, Vincenzo Borg in the central regions, while Francesco Saverio Caruana led in the west. For perhaps the first time in their history, the Maltese were fighting as a unified people—though the terrible price of this unity was the civil war that had preceded it.

By summer 1800, with Napoleon’s fortunes changing in Europe and his forces in Egypt defeated, the French situation in Malta became untenable. General Vaubois, having held out far longer than expected, finally surrendered to British forces on September 5, 1800. The tricolour came down. Union Jack rose.

I saw it again, one master replaced by another.

But this time, the Maltese had fought for themselves. Had organized, strategized, sacrificed. Had tasted what it meant to act rather than be acted upon. The spirit that had sustained them during the Great Siege had awakened once more.

Perhaps one day, these lands will taste freedom. Self governance.

Vincenzo Borg stood at the entrance to Ta’ Xindi Farmhouse, watching British troops march into Valletta. Beside him, Matthew Pulis leaned heavily on a cane, his leg never fully healed from a French bullet.

“We did it,” Pulis said simply.

Borg nodded. “And what did we win?”

“Our dignity. Perhaps a voice, next time decisions are made about Malta.”

“And what did we lose?”

“Too much,” Canon Caruana said, joining them. The cleric’s face was lined with exhaustion, his once-clean hands now permanently stained with gunpowder. “Twelve thousand Maltese dead by Maltese hands. Villages emptied. Families destroyed. A generation marked by fratricide.”

Pulis had no answer for that. All three men knew the cost. Almost every family had a grave to tend. A widow to support. An orphan to raise. And something less tangible—innocence, perhaps. The belief that neighbors would always remain neighbors, regardless of politics.

I felt the same ambivalence beneath the surface. The same mixture of relief and uncertainty.

The French occupation had changed Malta in ways both visible and invisible. Churches were poorer in gold but richer in stories of resistance. Villages had lost sons but gained heroes. And the Maltese, who had lived under the rule of others for so long, had learned something about their own strength.

Yet I mourned what was broken. The trust between cousins in that tavern in Żebbuġ. The childhood of the boy who killed his first man at Mriehel. The unity that had once allowed disagreements without blades drawn.

The irony was not lost on any of them. The British, initially welcomed as liberators, had no intention of granting Malta true independence. In the years to come, there would be talk of returning the islands to the Knights, but the Maltese would fight with words and petitions where once they had fought with swords. The wind would shift again and again, with Malta passed like a chess piece between greater powers.

I had seen this pattern before. Would see it again. Islands in the middle of the sea are never truly their own masters for long. But the spirit of resistance, once awakened, never truly dies.

That evening, as British ships filled Grand Harbour and celebration fires dotted the hills, I stretched my awareness across the island. Brushed against the still-warm barrels of cannons captured at Mriehel. Lingered in the square where Maria had fallen, where children now played again as though nothing had happened.

I am not a god. Not a force for vengeance or justice. Just a watcher who had begun, reluctantly, to participate.

The lightning had changed me, yes. But Malta had changed me more.

I could no longer observe passively when my people bled. Could no longer remain silent when bombs fell on churches. Could no longer stand apart when the very limestone of Malta cried out for protection.

What I was becoming, I did not know. But whatever it was, it belonged to Malta. As it always had.

Centuries watching Now learning to move, to act Still limestone at heart

The French had gone. The British had come. And Malta endured, as it always would.

And I, Il-Ħares, with be here to endure with it.