Introduction

Malta’s story is often recounted through tales of the Knights of St. John or British colonial rule. Yet, a lesser known era—the Arab period—has profoundly shaped the island’s culture, language, and architecture. From the 9th to the 11th centuries, Malta was part of the Arab-Islamic world, leaving legacies that resonate in Maltese society even today. For a broader historical context, consider this overview of Malta’s past. This article explores how the Arab influence has endured, shaping everything from the Maltese language to architectural styles across the islands.

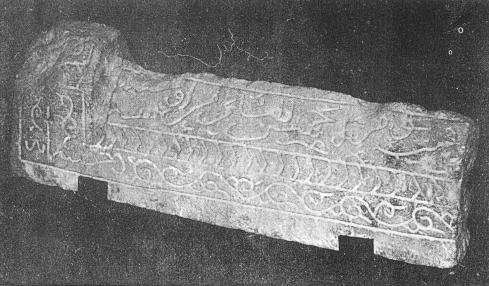

Featured image caption : Maltese Arabic Script Crop on a Tombstone – Source: Malta: Studies of its Heritage and History, edited by Mid-Med Bank (Malta, 1986), pp. 87-104. “The Arabs in Malta” by Godfrey Wettinger, p. 87. Accessed via: Ashashyou on Wikimedia Commons.

Linguistic Legacy

The Maltese language stands as the most visible remnant of the Arab period. Although modern Maltese contains Italian loanwords, at its core, it is a morphologically Arabic language, uniquely using the Latin alphabet. Historian Maxine Robinson aptly noted that “Islam may have disappeared after 1249, but an Arabic dialect is still spoken by the mass of [the] population” (Robinson 1981). With roots tracing back through North African Arabic, this linguistic heritage aligns Malta more closely with its southern neighbors than many realize. For a sense of Malta’s deep linguistic history, including earlier Semitic influences, examine Malta’s Phoenician connections. Despite centuries of effort to “Europeanize” the language, Maltese remains deeply Semitic at its foundation.

Here’s the table with the Maltese words as the first column, followed by Egyptian Arabic, Tunisian Arabic, Algerian Arabic, Moroccan Arabic, Italian, and Sicilian equivalents:

| Maltese | Egyptian Arabic | Tunisian Arabic | Algerian Arabic | Moroccan Arabic | Italian | Sicilian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| skola | madrasa | madrasa | madrasa | madrasa | scuola | scòla |

| dar | bayt | dar | dar | dar | casa | casa |

| ħobż | ʿēsh | khobz | khobz | khobz | pane | pani |

| ilma | māya | ma | ma | ma | acqua | acqua |

| zokkor | sukkar | sukkar | sukkar | sukkar | zucchero | zuccaru |

| suq | sūq | sūq | sūq | sūq | mercato | mercatu |

| xogħol | shughl | khidma | khidma | khidma | lavoro | travagghiu |

| tieqa | shubāk | tbība | tbība | tbība | finestra | finestra |

| kafè | ‘ahwa | kahwa | qahwa | qahwa | caffè | cafè |

| dawl | nūr | dū | nūr | nūr | luce | luci |

| lingwa | lugha | lugha | lugha | lugha | lingua | lingua |

| raġel | rajul | rajel | rajel | rajel | uomo | omu |

| moskea | masjid | masjid | masjid | masjid | moschea | muschea |

| re | malik | malik | malik | malik | re | re |

| ħin | waqt | waqt | waqt | waqt | tempo | tempu |

| ġnien | bustān | bustan | bustan | bustan | giardino | jardinu |

| platt | tabaq | tbīqa | tbīqa | tbīqa | piatto | piattu |

| sikkina | sikkin | mus | mus | mus | coltello | cuteddu |

| xemx | shams | shams | shams | shams | sole | suli |

| baħar | bahr | bahr | bahr | bahr | mare | mari |

| ħajt | hayt | ħayt | ħayt | ħayt | muro | muru |

| wieħed | wāḥid | wāḥid | wāḥid | wāḥid | uno | unu |

| tnejn | ithnān | ithnayn | zūj | jūj | due | dui |

| tlieta | thalātha | thalātha | tlata | tlata | tre | tri |

| erbgħa | arbaʿa | arbaʿa | rbʿa | rbʿa | quattro | quattru |

| ħamsa | khamsa | khamsa | khamsa | khamsa | cinque | cincu |

This structure allows for easy comparison, with Maltese as the reference point.

Architectural and Urban Design

The Arab period influenced Malta’s urban landscape in ways that have subtly persisted. Narrow, winding streets and courtyard-centric homes—common in Arab design—offered shade and privacy suitable for the Mediterranean climate. Decorative elements, such as arabesques, are still evident in religious art. For example, Islamic-inspired motifs can be observed in historical fortified structures, and although the original text mentioned St. John’s Co-Cathedral in Mdina, in reality, St. John’s Co-Cathedral is located in Valletta. Still, the Mdina cityscape and Valletta’s religious monuments incorporate subtle echoes of Islamic aesthetics.

Arab-influenced structures like Fort St. Angelo, where architectural techniques reflect earlier styles, and the fortified cityscapes recall how Arab builders utilized strategic construction to protect inhabitants. For more on medieval strongholds that evolved over time, consider Castrum Maris. These architectural features helped shape Malta’s identity as a fortified island prepared for both commerce and conflict.

Religious and Cultural Shifts

During the Arab period, Islam became the predominant faith. Although later Christianized under Norman rule, remnants of Islamic culture remained. The Maltese phrase “jekk Alla jrid” (if God wills) echoes the Arabic “insha’ Allah.” The pattern of church bells ringing multiple times a day parallels the Islamic call to prayer, albeit now within a Catholic framework. Traditions like Randan (Lent) carry echoes of Islamic practices adapted into Christian rituals. As time passed, new rulers—eventually including the Knights—reshaped religious life. Learn more about their legacy at The Knights of Malta. Thus, while faith structures shifted, the cultural imprints of Islam endured beneath the Christian veneer.

Agricultural Innovation and Economic Prosperity

Arab rule introduced advanced agricultural techniques, including waterwheels and animal-powered devices for irrigation. This innovation supported the growth of citrus fruits and cotton—transforming Malta’s landscape. To delve deeper into the island’s evolving relationship with water, see ancient and modern water solutions in Malta. One Arab chronicler praised Malta as “a blessing from God… well populated, with towns and villages, trees and fruits.” Such prosperity solidified Malta’s role as a trading hub, and this economic foundation echoed through the centuries.

Strategic and Military Significance

Malta’s position in the central Mediterranean made it a valuable maritime base for the Arab Empire. Used to dominate shipping lanes and repel Byzantine attacks, Malta evolved into a defensive outpost and corsair haven. Its strategic role in projecting Arab naval power laid the groundwork for later maritime activities. Explore how these practices persisted by examining the history of piracy from Malta. Over time, these defensive and naval traditions shaped Malta’s identity as a heavily fortified, sea-conscious nation.

Poetry, Music, and Oral Traditions

The Arab period fostered a vibrant cultural life, including poetry and oral traditions. Maltese folk singing, known as għana, may trace its roots to Arabic zajal. This improvisational art form persists in rural communities, reflecting deep cultural continuity. For more on the historical layers that influenced cultural resilience in Malta, consider the early foundations of the Three Cities. Artistic expressions, passed down orally, help keep alive the memory of Arab cultural contributions within Malta’s collective heritage.

Language of Place Names

Many Maltese towns and natural landmarks retain their Arabic names. Terms like Bahar (sea), Bir (well), and Wied (valley) remain common. Place names such as Marsa (harbor), Sliema (derived from a form of greeting), and Mdina (city) root modern Malta in its Arab past. For insights into these historically important towns and their evolution, see the history of the Three Cities and how they preceded later European influences. To understand why fortress cities were developed, including these harbor towns, consider the strategic reasons for Malta’s fortified cities.

The Three Cities: Birgu, Isla, and Bormla

Under Arab rule, Malta’s harbor towns—later known as the Three Cities—began their rise as strategic maritime points. The Arabs recognized the value of these natural harbors, fortifying them and laying the groundwork for what would become Birgu, Isla (Senglea), and Bormla. Over time, this region grew into a hub of Mediterranean trade and naval operations. The legacy of their original layout—narrow streets for defense and shade—would later support Malta’s resistance during great conflicts. Their Arab-influenced urban planning reinforced Malta’s ability to adapt and survive sieges. For further context on early maritime development, explore the Three Cities before the Knights.

Conclusion: Malta’s Enduring Arab Heritage

Although Arab rule in Malta concluded nearly a thousand years ago, its influence remains woven into the nation’s cultural fabric. From the fortification ethos that endured to the linguistic, religious, and artistic elements that persisted beneath subsequent layers of European rule, the Arab legacy is unmistakable. Malta stands as a unique Mediterranean society, where Arab and European traditions have merged into a rich and resilient cultural heritage—living proof that ancient influences need not vanish, but can thrive and evolve over centuries.

References

Dalli, Charles. 2003. “Greek, Arab, and Norman Conquests in the Making of Maltese History.” Storja. University of Malta.

Dalli, Charles. 2006. Medieval Malta: The Making of a Christian Kingdom. Malta: Midsea Books.

Luttrell, Anthony T. 1992. Byzantine and Muslim Malta: 5th to 11th Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, Maxine. 1981. The Arabs. Translated by A. Goldhammer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wettinger, Godfrey. 2019. The Arabs in Malta. Malta: The Sunday Times of Malta.