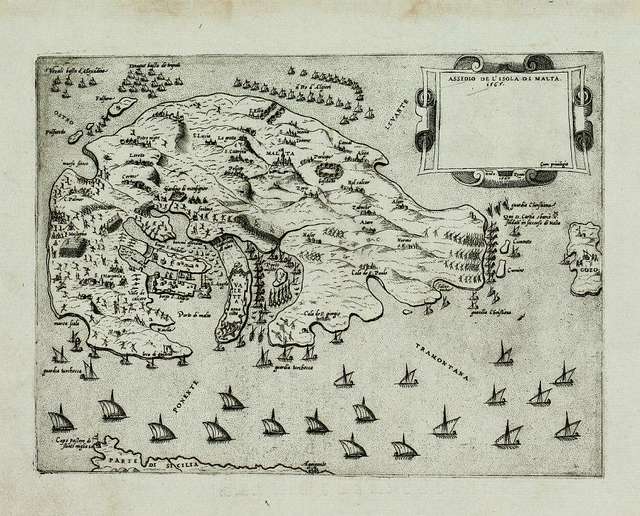

Located on Malta’s historic peninsula, the medieval fortification known as Castrum Maris—later known as Sant’Angelo—played a significant role in the island’s history. Built during Malta’s Byzantine and possibly even earlier periods, it evolved over centuries, adapting to the demands of military defense and the needs of local governance. This article delves into the fort’s medieval history before the arrival of the Knights of St. John in 1530, focusing on its construction, architectural details, and significance as a defense stronghold and community hub.

Early Beginnings and Strategic Evolution

The origins of Castrum Maris trace back to Roman or Byzantine periods, as suggested by its oldest stones, possibly repurposed from ancient structures. While records lack details on its initial construction, the fort displays similarities with castles built in Sicily during the 11th and 12th centuries, reflecting influence from both Byzantine and Arab architectural styles. The site’s high ground provided a tactical advantage, with multiple defensive layers including thick, imposing walls, fortified gates, and strategically placed round towers.

Key Defensive Features

The first detailed description of the fort in 1274 reveals it was divided into two main sections: the castro exteriore (Outer Castle) and the castro interiore (Inner Castle), separated by high ramparts reinforced with round towers at regular intervals. These fortifications provided platforms for soldiers to defend against attackers, while a ditch divided the upper and lower parts, serving as an additional barrier. Excavations during restoration uncovered remnants of two Medieval towers, demolished in the late 18th century, and confirmed the survival of one intact tower. The final set of towers, constructed under the supervision of Antonio Fantino in 1523, illustrates the fort’s evolution to meet changing defensive needs.

Medieval defense strategies are visible in Castrum Maris’s structure. The outer and inner castles, separated by high walls, featured defensive round towers spaced at intervals to support soldiers during sieges. (Which is an architectural feature we see over and over again in history : Osaka Siege vs The Great Siege) The castle’s levels required attackers to navigate a series of gates, making each layer progressively harder to breach. A moat separated the upper and lower sections, enhancing the fort’s defensive posture, while sections of the medieval moat remain visible today.

The barbican, built in the 15th century, served as a protective gateway, defending the entrance in case of attack. Although barbicans were often cylindrical, space limitations at Castrum Maris led to a rectangular design. Additionally, Malta’s first documented artillery battery was positioned at Castrum Maris, securing the Grand Harbour entrance—a strategic element not commonly seen in other European fortifications of its time.

The Castle’s Religious and Administrative Role

The castle housed more than military facilities; it also included religious and administrative buildings. A chapel, initially dedicated to Santa Maria and later to Sant’Anna, served as a place of worship, indicating the importance of faith within the fort’s walls. Administratively, a Castellan, appointed by the ruling authority, managed the fort, wielding significant power over the fortress and its inhabitants. This system persisted under different rulers, including the Hohenstaufen, Anjou, and Aragonese dynasties.

In 1241, records describe the castle’s grain mill and wine cellars, indicating selfsufficiency within the walls. These facilities often sparked disagreements between the Castellan and Mdina’s leaders over taxation on goods produced in the castle, revealing how Castrum Maris served not only as a fortress but also as an economic microcosm.

Social and Residential Aspects

By the 15th century, around 40% of Birgu’s households were within the castle’s walls, likely families of soldiers and workers stationed there. The fort’s upper section housed residential quarters, while its lower levels might have included housing for the broader community involved in fort maintenance and support roles.

The Dockyard and Prison Complex

Castrum Maris was more than just a defensive site; it housed a dockyard (first mentioned in 1374) and served as a detention center from as early as 1275. The dockyard’s presence hints at the site’s role in maritime activity, while the prison reinforced its place in local governance. Its importance grew with time, evidenced by expansions and repairs in the late 14th and 15th centuries to maintain the fort’s readiness for potential threats.

Architectural Resilience and Adaptation

Frequent repairs and enhancements marked Castrum Maris’s history. In the 1420s, repair taxes on wine helped cover costs after periods of neglect, and significant structural repairs occurred in 14771478, including a newly constructed wall and the reinforcement of towers. By the late 15th century, its cannon resistant walls became vital as Ottoman incursions heightened, underscoring the fort’s adaptive capacity to new military technologies and threats.

Conclusion

Castrum Maris was a cornerstone of Malta’s medieval defense, governance, and community life. Its architecture and role evolved to adapt to shifting power dynamics and technological advancements, cementing it as a key piece of Malta’s medieval heritage. The fort’s resilience—seen in its structural adaptations and social significance—kept it at the core of Maltese defense until the arrival of the Knights of St. John, marking the beginning of a new chapter. This fort was the first step in establishing the fortresses of the Three Cities. In the 1200s, the Knights, French, English, and Turks had yet to reach these lands, and Malta had yet to witness much of the human suffering that would follow.

In a way Castrum Maris was the first foundational stone for the three cities and their history.

References

1. Spiteri, Charles B. “LEvoluzzjoni talCastrum Maris filMedjuevu.” One, 13 Sept. 2020.

Bosio Dell’Istoria Della Sacra Religione Et Illustrissima Gierosolomitana (parte 12)

Bosio Dell’Istoria Della Sacra Religione Et Illustrissima Gierosolomitana (parte 12) : Giacomo Bosio : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Stay in Gżira near the promenade

A designer 2-bedroom apartment in Gżira, close to the church, around 2 minutes from the promenade, and near Manoel Island.

View on Airbnb