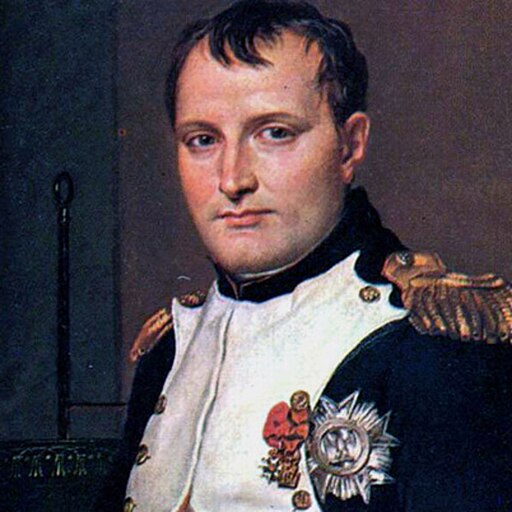

The late 18th century was a period of intense upheaval in Europe, marked by the sweeping changes of the French Revolution and the ambitious military campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte. Among the many events that reshaped the continent, the French invasion of Malta in 1798 stands out as a significant turning point for the small Mediterranean archipelago. This event not only altered the course of Maltese history but also left an indelible mark on its cultural and architectural heritage.

Setting the Scene

Malta, strategically nestled between Europe and Africa, had long been under the control of the Sovereign Military Order of St. John, also known as the Knights Hospitaller. Led by Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim, the Knights had ruled Malta since 1530, transforming it into a fortress island renowned for its formidable harbors and fortifications. However, by the late 18th century, the Order’s influence was waning. Internal strife, financial difficulties, and a growing disconnect with the local Maltese population left the island vulnerable.

Amidst this backdrop, Napoleon Bonaparte eyed Malta as a crucial stepping stone for his eastern ambitions. In his quest to challenge British dominance and expand French influence, Egypt was his primary target. Controlling Malta would provide the French navy with a strategic base in the Mediterranean, securing supply lines and offering a formidable position against adversaries.

The French Fleet’s Arrival and Demands

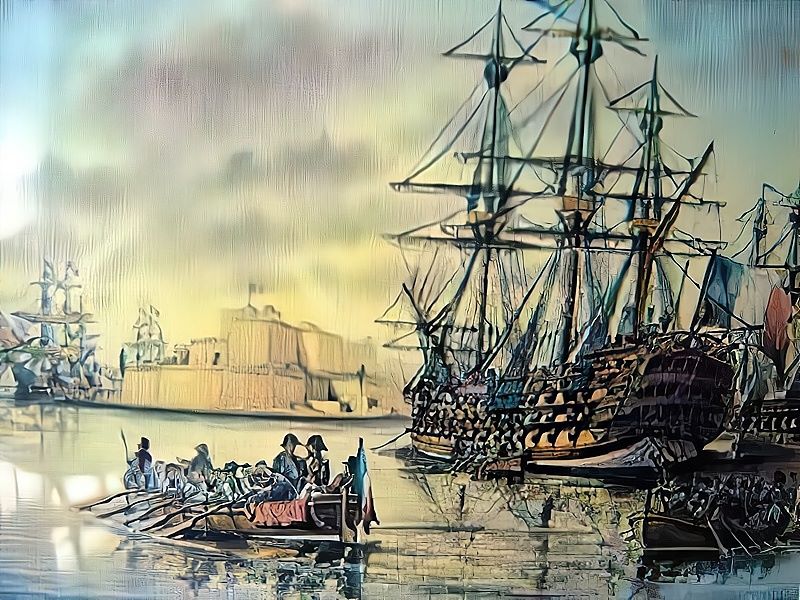

On June 9, 1798, the horizon off Malta’s coast was filled with the imposing sight of a massive French fleet. Over 30,000 soldiers aboard numerous ships signaled an unmistakable intent. Napoleon’s forces had sailed from Toulon, gathering additional vessels along the way, and now anchored off Valletta, Malta’s fortified capital.

Napoleon wasted no time in sending a message to Grand Master Hompesch, demanding that his fleet be allowed safe harbor to resupply. Citing Malta’s neutrality, Hompesch offered a compromise: only two ships could enter at a time. This restriction was unacceptable to Napoleon, who viewed it as a thinly veiled attempt to hinder his campaign. The standoff was more than a diplomatic disagreement; it was a clash of wills between an aging order and an ambitious general.

The Capitulation and French Takeover

Refusing to be delayed, Napoleon ordered his forces to commence hostilities. On June 11, General Louis Baraguey d’Hilliers led an amphibious assault, landing troops at seven strategic points around the island. The Knights’ defenses crumbled rapidly. Many of the French Knights within the Order defected, and the remaining forces were ill-prepared for a prolonged fight.

The Maltese militia, numbering around 2,000, offered resistance but were outmatched by the seasoned French troops. After just 24 hours of skirmishes, and with the city of Mdina captured by General Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois, Grand Master Hompesch entered into negotiations. On June 12, the Knights agreed to surrender Malta to the French Republic in exchange for pensions and safe passage.

For the Maltese population, the swift fall of the Knights was a shock. While some harbored resentment towards the Order due to economic hardships and social disparities, others were wary of foreign domination. The French arrival heralded a new era, but one whose implications were yet uncertain.

The Spark of Rebellion

By the summer of 1798, tensions on the island of Malta had reached a boiling point. Following the swift and largely unopposed takeover by the French—who had ousted the centuries-old rule of the Knights of St. John—local dissatisfaction mounted. The Knights, once a formidable force known as Europe’s First Pan-European Organization, had been weakened by internal strife, financial troubles, and shifting geopolitical currents. This vulnerability opened the door to French occupation, which arrived with both revolutionary ideals and secular reforms that challenged deeply rooted Maltese traditions.

The breaking point came on September 2, 1798, during an auction of church property in Mdina. Outraged Maltese locals, unwilling to see their cherished institutions dismantled and sacred objects sold off, violently disrupted the event. This uprising, though sudden, had deep roots in existing discontent and cultural tensions. News of the revolt spread quickly to the countryside, prompting villagers to arm themselves against the occupying French forces. To understand this backdrop, exploring A Brief History of Malta provides essential context.

Napoleon’s Reforms: A Mixed Legacy

During his brief stay of six days in Malta, Napoleon introduced a series of sweeping reforms shaped by French revolutionary ideals. In theory, these policies aimed to modernize Maltese society:

- Feudal rights of the Knights were abolished, dismantling the aristocratic structure that had prevailed for centuries.

- Secular education replaced the traditional, ecclesiastically influenced system. The University of Malta was substituted with a centralized school system, and French was declared the official language.

- Religious freedoms were extended to Jews and Orthodox Greeks, a notable shift in a predominantly Catholic nation.

- Slavery and the “buonavoglia” system—indentured servitude of sailors—were abolished.

- Civil marriage was legalized, and new governance structures emerged, blending Maltese notables with French officials.

While some measures were progressive, they were executed abruptly, with little sensitivity to longstanding local customs. Religious orders were suppressed, and church property was seized to fund French military activities. To many Maltese, especially the clergy and devout populace, these reforms felt like a direct assault on their faith and identity rather than a path to enlightenment.

Economic and Religious Impact

Financial policies under French administration quickly exacerbated tensions. Hefty taxes and forced requisitions—combined with the seizure and melting down of church treasures—created a widespread perception of economic exploitation. Beyond material loss, these acts were seen as sacrilege, striking at the heart of Maltese religious life.

The sudden imposition of secularism and disregard for ecclesiastical authority clashed with the island’s deeply ingrained Catholic values. The clergy, who wielded substantial influence in Maltese society, openly voiced dissent. As economic hardships mounted and the promises of liberty, equality, and fraternity rang hollow, the disillusioned populace found itself increasingly at odds with its new rulers.

Leaders of the Insurgency and a Fractured Power Structure

Key figures soon rose to guide the growing resistance. Canon Francesco Saverio Caruana used his religious standing to unify the faithful. Notary Emanuele Vitale organized militias and coordinated actions across multiple regions. Vincenzo Borg, known as “Brared,” stirred the public with passionate oratory and strategic vision. None of these leaders were traditional soldiers, and their forces lacked the professional training or foreign backing enjoyed by the Knights during the island’s earlier conflicts, such as the famed Great Siege of Malta of 1565.

Yet, the Maltese held an invaluable advantage: intimate knowledge of their homeland’s terrain. Drawing on defensive strategies honed over centuries of foreign threats, they choked off French garrisons from vital supplies. As the French withdrew into the fortified heartlands of Valletta and the Three Cities—Senglea, Vittoriosa (Birgu), and Cospicua—these once impregnable strongholds, originally fortified by the Knights, now became cages for their new occupiers. For insight into the French military approach, see Military Tactics Used by the French in the Invasion of Malta 1798 and Why Did the Knights of Malta Built the Three Fortress Cities?.

Seeking Allies and the British Intervention

As rebellion intensified, the Maltese leaders looked abroad for support. While the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies offered limited help, it was Britain that recognized Malta’s strategic importance and answered the call. Captain Sir Alexander Ball proved pivotal in securing Maltese trust and orchestrating a naval blockade. To learn more about this critical pressure point, consult The Blockade of the Three Cities by the Maltese vs the French.

The siege of Valletta from 1798 to 1800 tested everyone’s endurance. While the French were skilled soldiers, the Maltese demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Their perseverance under starvation, hardship, and uncertainty eventually bore fruit: by 1800, the French surrendered, and the British assumed a lasting and influential presence on the island. For comparative analysis, Comparing the Military Tactics of the Two Great Sieges of Malta 1565 and 1798 provides additional perspective.

Cultural and Societal Aftermath

The French occupation may have been brief, but it reshaped Malta’s destiny. It toppled the Knights’ feudal order, introduced secular policies, and sparked a sense of national consciousness as the Maltese mobilized to defend their religious and cultural heritage. While some French reforms outlasted the occupation and nudged Malta toward modernity, the collective memory of confiscated church property and heavy-handed rule lingered.

The ensuing British alliance further influenced Maltese governance, economy, and society, setting the stage for Malta’s emergence as a crucial strategic outpost well into the 20th century. Over time, layers of foreign rule—Phoenician, Arab, Norman, Knights, French, and British—formed the complex mosaic that defines Malta’s identity today.

A Living Legacy in Malta’s Landscape

For visitors and historians, the legacy of the French invasion is palpable. Fortifications like St. Elmo Fortress and Fort St. Angelo still stand as silent witnesses to these turbulent times. Strolling through Valletta’s bastions or Birgu’s narrow alleys, one can sense echoes of that era when old powers gave way to new visions and local patriots rose against imposing forces.

The story of the Knights, chronicled in The Knights of Malta, sets a historical backdrop that makes understanding the French period richer and more nuanced. Museums, guided tours, and scholarly works draw from this legacy to provide a fuller picture of how Malta’s cultural resilience has endured through centuries of change.

Conclusion

The French invasion of 1798 was far more than a passing footnote in Maltese history. It was a crucible of reform, resistance, and rebirth that reverberated through the island’s social, political, and spiritual life. While Napoleon’s reforms introduced elements of modern governance and social justice, their abrupt and often insensitive implementation provoked fierce opposition. In the long run, the Maltese emerged not as passive subjects but as active architects of their future.

Understanding this chapter enriches any encounter with Malta today. It illuminates how an island, small in size yet significant on the European stage, continually adapted to foreign pressures. From the bold experiments of the French to the determined resistance of its people, Malta’s story in 1798 remains a testament to resilience, national identity, and the complex dance between tradition and change.