A Timeline of Resistance and Survival

1530s–1550s: Formation of Local Militia Tradition: Even before the Knights arrived, the Maltese had a history of forming militias to defend against pirate raids. Castles already existed like Castrum Maris. When the Knights established themselves in Malta, they integrated local militias as auxiliary forces, bolstering defenses with Maltese manpower and local knowledge.

1530: Knights of St. John Settle in Malta: After being expelled from Rhodes by the Ottomans in 1522, the Knights of St. John were granted Malta by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, in 1530. This settlement positioned them in a strategic location in the Mediterranean, directly in the path of Ottoman expansion.

1530s: Initial Fortifications Begin: The Knights start to reinforce the existing fortifications on Malta, particularly around the Grand Harbour area and the three cities. Birgu becomes the Knights’ primary stronghold, and early defenses are constructed to protect the island from potential Ottoman threats.

1540s: Accumulation of Wealth and Power: Over the next decade, the Order of St. John amasses wealth through donations, taxation, and control of trade routes (aka Piracy). As the Order’s wealth grows, so does its ability to fund more substantial defensive projects and bolster its naval power, becoming a significant player in Mediterranean politics by constructing the three fortress cities. The order kept monopolies on all commodities on the island and taxed the locals, still some Maltese entrepreneurs managed to do business.

1547–1551: Increased Ottoman Raids in the Mediterranean: Ottoman forces launch frequent raids on Christian territories, including the Italian coast and Sicily. These raids demonstrate the Ottoman threat to Malta and the wider Christian Mediterranean, and the Knights intensify their corsair and fortification efforts in response.

1551: Ottoman Attack on Gozo and Loss of Tripoli: July 1551: The Ottomans, led by Dragut and Sinan Pasha, attack Gozo, enslaving nearly all inhabitants. Shortly after, the Ottomans capture Tripoli, a North African possession of the Knights. The loss of Tripoli highlights the need for stronger defenses on Malta.

1551: Maltese Militia Response to Ottoman Attacks on Gozo: During the Ottoman raids, including the devastating attack on Gozo, local militias resisted as best as possible, though limited in weaponry and support. This experience underlined the importance of a prepared and fortified militia force for future defense needs.

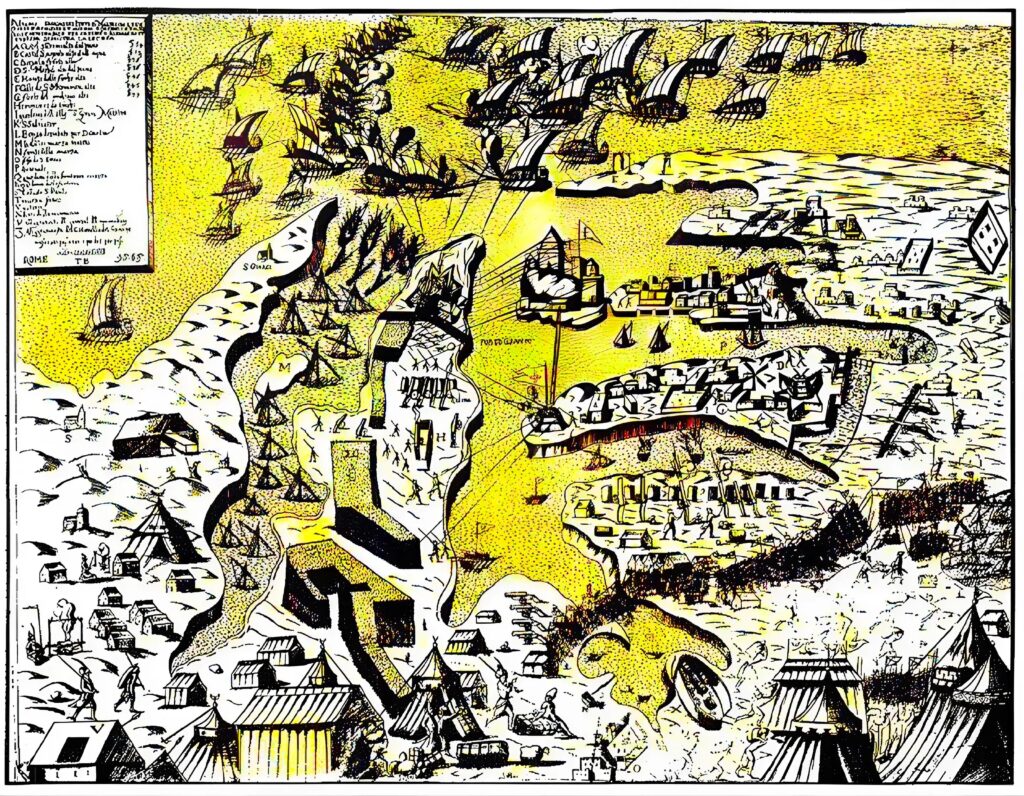

1552: Construction of Fort St. Elmo: In response to the Ottoman threat, the Knights begin constructing Fort St. Elmo on the Sciberras Peninsula, overlooking the entrance to the Grand Harbour. Fort St. Elmo is strategically positioned to defend against a naval invasion and protect the Grand Harbour and surrounding settlements.

1557: Jean Parisot de La Valette Becomes Grand Master: August 21, 1557: La Valette, a seasoned and determined leader, is elected Grand Master. He immediately prioritizes the defense of Malta, initiating the construction of additional fortifications and strengthening the Knights’ fighting capabilities in anticipation of an Ottoman assault.

1561–1564: Fortification of Senglea and Birgu: Under La Valette’s direction, the Knights expand the defenses of Birgu and Senglea, constructing walls, bastions, and other fortifications to make these settlements more resilient against a siege. La Valette also reinforces Fort St. Angelo in Birgu, preparing it as a last line of defense.

1563-1565: Intense Recruitment and Training of Maltese Militia: In anticipation of the Ottoman siege, Grand Master La Valette organized, trained, and equipped local Maltese militias alongside the Knights’ forces. The militia would serve as vital reinforcements, capable of both combat and logistical support during the siege.

1564: Espionage and Warnings from Constantinople: The Knights receive intelligence from spies in Constantinople indicating Ottoman preparations for a large assault on Malta. La Valette uses this information to strengthen fortifications further and increase recruitment and training of soldiers.

1555: Pre-Siege Intelligence: Grand Master Jean Parisot de La Valette and the Order received warnings from spies well in advance of the Ottoman fleet’s departure, allowing them to initiate their defensive preparations. Historian Roger Crowley, in Empires of the Sea, details how La Valette was well-informed about the size and timing of the Ottoman expedition through a network of informants.

January – May 1565: Intensified Preparations and Reinforcements

As reports of an imminent Ottoman assault reached the Order, preparations on Malta intensified. Grand Master Jean Parisot de La Valette took decisive action by:

- Recruiting additional soldiers from Naples, Sicily, and Spain, significantly bolstering the island’s defenses with fresh troops.

- Implementing defensive taxes to fund the war effort.

- Beginning the evacuation of non-combatants and nobles from Malta to safeguard civilians.

These measures were crucial as the threat of the Ottoman fleet became increasingly real, allowing the Order to gather supplies, weaponry, and manpower necessary to face the upcoming siege

March 1565: The Ottoman Empire assembles one of its largest naval forces, consisting of approximately 180 ships, including galleys, galliots, and other vessels, intending to conquer Malta and use it as a base for further Mediterranean expansion.

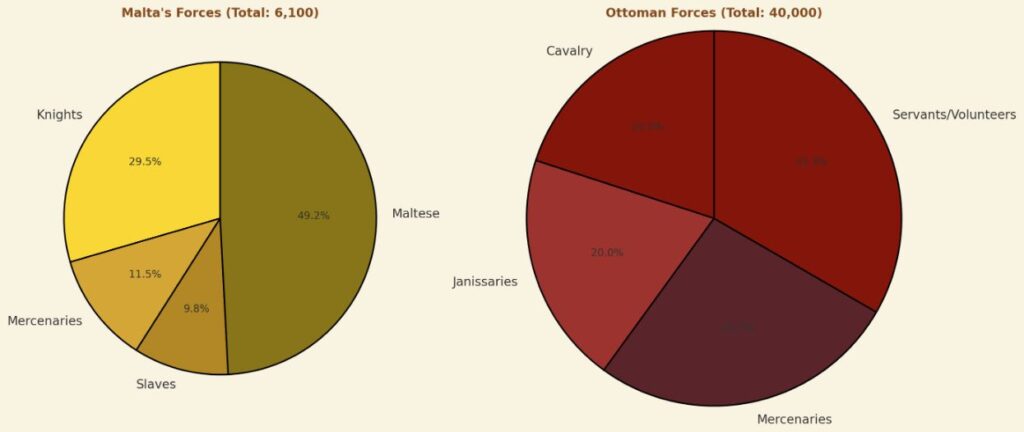

May 1565: Arrival of the Ottoman fleet : The formidable Ottoman fleet, under Piali Pasha, arrives off Malta. The Ottoman forces, numbering around 25,000 men+, include elite Janissaries and are joined later by Dragut’s fleet. The sight is described as a fearsome spectacle of disciplined and determined soldiers.

May 18, 1565: The first contingent of Ottoman troops lands at Marsaxlokk Bay. They establish an initial base of operations to prepare for the assault on the Maltese fortifications. This event marked the start of the full-scale invasion.

May 19, 1565: Elite unit of the Maltese militia activated:—Toni Bajada, Andrew Zahra, James Pace, Anton Cascia, and Francis Xerri—closely tracked the Ottomans’ movements, gathering essential military intelligence. Some of these operatives had previously been captured by the Turks and spoke Turkish fluently, allowing them to infiltrate the Ottoman camps undetected. Blending in the 25,000 Ottoman troops, was challenging but feasible, enabling them to gather intelligence vital to the Maltese defense.

May 20, 1565: Ottoman forces land at Marsaxlokk, avoiding defended harbors to safely establish their base of operations.

May 27, 1565: The siege of the three cities and in particular Fort St. Elmo begins. Ottoman artillery, positioned on the Sciberras heights, unleashes relentless bombardment on the fort, marking the first phase of the siege. The defenders reinforce themselves as Maltese civilians attempt to provide supplies covertly under cover of darkness.

Late May – Early June: Legendary tales speak of Toni Bajada from Naxxar : who swam across the Grand Harbour at night to carry messages between the defenders at Fort St. Elmo and the main fortifications at Birgu. This swimmer’s daring efforts sustain the Knights’ communications in these critical early weeks of the siege.

Late May – June 23, 1565: Maltese Civilian Involvement in Resupply Efforts : Maltese civilians supported the Knights by covertly delivering supplies, especially to Fort St. Elmo, which was heavily besieged between May 27 and June 23. These daring missions were often conducted under cover of night to avoid detection, as civilians risked their lives to bring food, water, and other essentials to the defenders.

June 2, 1565: The Ottomans capture the ravelin at Fort St. Elmo, edging closer to the inner defenses. Despite ongoing losses, the defenders refuse to surrender.

June 10, 1565: The Ottomans control the northern part of Malta, they in fact control the other side of the harbour on the Manoel Island side. Fort Manoel on Manoel island was constructed after the great siege.

June 18, 1565: Turgut Reis (Dragut), a renowned Ottoman commander and key figure in their strategy, is mortally wounded by cannon fire. His death significantly impacts Ottoman morale and strategy.

June 23, 1565: Fort St. Elmo falls after a month-long siege. Only a few defenders survive, many of whom are severely wounded. Enraged, Ottoman troops mutilate the Knights’ bodies and float their crosses across the harbor as intimidation toward the defenders in Birgu and Senglea. The Knights retaliate by beheading captured Ottoman soldiers and firing their heads back by cannon.

July 15, 1565: A coordinated Ottoman assault on Senglea by both land and sea fails. Intelligence leaks and the Knights’ defensive preparations thwart the attack. A sudden storm disrupts Ottoman operations, which defenders interpret as divine intervention.

Maltese and Knight forces use fire hoops and incendiary materials to repel the attackers, demonstrating the ingenuity of the defenders.

July 1565: Religious and Cultural Rallies Among the Defenders : Religious observances and the interpretation of natural events as divine support occurred throughout the siege. One particularly impactful incident happened in July, when a sudden storm disrupted an Ottoman attack on Senglea. The Knights and Maltese saw this storm as divine intervention, bolstering their determination to resist.

August 7, 1565: The Ottomans launch a significant assault on Birgu. A sudden cavalry raid from Mdina surprises the Ottoman rear, creating the impression of a much larger Christian relief force. The Ottomans retreat in confusion, allowing the defenders to regroup. giving the defenders at Birgu and Senglea much-needed respite.

August 7, 1565: Grand Master de Valette personally leads a sortie against Ottoman forces attempting to breach the walls of Birgu, inspiring the defenders.

August 19 – Late August: The Ottomans repeatedly bombard Birgu and Senglea, using siege towers and makeshift bridges to cross defenses. Ingenious defenses by the Knights, including flaming tar and oil, counter these attempts. Tales suggest civilians joined in, throwing boiling oil onto Ottoman forces from within the city walls.

Late August 1565: Construction and Use of Ottoman Siege Towers : As the siege wore on and frustrations grew, the Ottomans built large siege towers and makeshift bridges to cross the defenses at Birgu and Senglea. These efforts likely occurred in late August, coinciding with intensified Ottoman bombardment aimed at breaching the Knights’ fortifications. The defenders countered with tactics such as flaming tar and boiling oil to disable the towers.

August 1565: Ottoman Logistical Challenges Worsen : By mid-August, Ottoman supply lines were severely strained. With the summer heat, maintaining provisions and managing disease became increasingly difficult. These logistical challenges led to declining morale and exacerbated internal disagreements among the Ottoman ranks, weakening their ability to maintain the siege.

Early September: Facing supply shortages and low morale, the Ottomans consider attacking Mdina but are deterred by an apparent show of cannon fire, likely an empty bluff by the defenders who hoped to appear stronger than they were.

Early September 1565: The Mdina Cannon Bluff: As Ottoman forces faced food shortages, disease, and declining morale, they considered an assault on Mdina. In response, the defenders, with limited artillery, executed a clever bluff: they fired their few cannons from multiple positions around the city, creating the illusion of a formidable arsenal. This simulated barrage convinced the Ottomans that Mdina was heavily fortified, deterring an attack.

The bluff succeeded, buying critical time for the defenders and sparing Mdina from the destruction suffered elsewhere. Shortly after, Don García de Toledo’s Spanish relief force arrived, forcing the Ottomans to abandon the siege. This deception stands as a notable example of psychological warfare, showcasing the resourcefulness of the Maltese and the Knights against a larger Ottoman force.

September 8, 1565: Ottoman forces begin withdrawing artillery from Malta, signaling the end of their siege. Across Malta, church bells ring in celebration, and civilians cheer for their survival.

September 13, 1565: Don García de Toledo’s Spanish relief fleet finally arrives, finding the Ottoman forces already in retreat. The Christian forces pursue them in a rout, though some accounts claim orders were to avoid a major naval engagement with the Ottoman retreat. The Ottomans leave behind a devastated landscape and numerous casualties, and Malta’s defenders chant the Te Deum in a triumphant display in Birgu’s St. Lawrence Church.

July 6–7, 1614: Raid on Żejtun : L-aħħar ħbit (“The Last Attack”) : The Ottoman Empire’s final major assault on Malta. This took place over two days, when a fleet carrying around 5,000–6,000 Ottoman soldiers landed on the island’s southeastern coast. Their primary target was the town of Żejtun, which, along with surrounding villages, suffered looting and destruction. However, the Order of St. John’s cavalry, along with armed locals, quickly organized a defense, pushing the Ottoman forces back to their ships and forcing a retreat. This raid effectively marked the end of the Ottoman Empire’s military campaigns against Malta, closing a chapter of direct Ottoman threats to the island.

Epilogue: Malta’s Legacy of Resistance and Transformation

Malta’s saga of resistance did not end with the Great Siege of 1565; its legacy continued through the ages. After the siege, the Knights of St. John not only solidified their reputation as defenders but also initiated the construction of Valletta, a fortress-city that would become a symbol of military engineering and urban planning. However, their naval prowess eventually led to their downfall, with Napoleon’s brief occupation in 1798 marking a turning point that introduced new reforms and ultimately led to the Knights’ expulsion. The resilience of the Three Cities during WWII mirrored the siege of 1565, showcasing their enduring strategic importance and the fortitude of the Maltese people. Arab rule also left a cultural imprint on Malta, influencing its language and agriculture, which laid a foundation for resilience that transcended the Knights’ era (see also : Arab influence).

Today, the fortifications and the very spirit of Malta stand as a testament to the island’s history of survival against sieges, reflecting a narrative of adaptation, resilience, and transformation. The island’s past continues to inspire contemporary culture and tourism. Tourists can explore these historical sites through various means, including self-guided tours, offering insights into how past sieges have shaped Malta’s identity. The narrative of resilience is not just historical; it echoes in the lives of digital nomads and in the enduring appeal of Malta as a destination for travelers seeking history, culture, and adventure, as detailed in European travel guides. The island’s past, with its mix of legends, military strategies, and cultural evolution, continues to captivate and educate visitors and residents alike.

Learn More about the three cities:

- Books and Movies that Feature the Three Cities

- Unique Experiences

- Getting There

- Parking

- Where to Eat

- Where to Stay

- One Day Self-Guided Tour

- Lesser Known Attractions

Reference:

Crowley, Roger. Empires of the Sea: The Siege of Malta, the Battle of Lepanto, and the Contest for the Center of the World. New York: Random House, 2008.