Welcome, fellow traveler of time and tales! Today, we’re going to wander deep into the ancient streets of Malta’s Three Cities—Birgu, Bormla, and Isla—and discover just how vibrant and interconnected their world really was long before the Knights of St. John set foot on these shores. This isn’t just a story about stone fortresses or old fishing boats bobbing along a marina; it’s a fascinating tapestry woven from many cultures—Phoenician, Roman, Arab, Norman—and countless generations of everyday people who lived, loved, and labored here. So buckle up. We’re rolling back the clock more than two thousand years to see what really happened in these remarkable communities.

A Glimpse into Malta’s Ancient Past

While the Knights of St. John are often credited with shaping Malta’s historic landscape, the roots of the Three Cities—Birgu, Bormla, and Isla—run much deeper, going back over two thousand years. Set along the natural haven of the Grand Harbour, these locations were already developing a unique identity as early as 800 BCE, when the Phoenicians established trading posts on the island. Over the centuries, Roman, Arab, and Norman influences left their mark, creating a cultural mosaic that thrived well before the Knights arrived in 1530.

By the 15th century, the total population of the Maltese Islands hovered around 20,000–25,000, with the Three Cities accounting for roughly 1,000–1,500 of those residents combined—hardly enormous by modern standards, but sizable for a small archipelago in the medieval Mediterranean. Historical sources suggest that, on average, a handful of trade ships docked at the Grand Harbour each month, ensuring a steady, if modest, stream of goods and cultural influences. Long before the Knights commanded the spotlight, an intricate cast of characters had already taken the stage. The Phoenicians brought their maritime prowess, weaving Malta into busy Mediterranean trade routes. These trade routes continued to develop and expand after the Kniights arrived : see here.

Later, the Romans introduced complex administrative structures, new religious practices, and sophisticated engineering—imagine elegant Roman villas near the waterfront and a legal framework uniting these islands with the broader Roman world. Under Byzantine influence, subtle religious art and fortified watchtowers emerged, while the Arabs refined agriculture, linguistic flavors, and irrigation techniques that forever changed what could be cultivated on these fertile plots of land. The Normans, Swabians, and Aragonese each layered on more feudal customs and religious traditions, gradually Latinizing and Christianizing the people. All of these eras delivered a cocktail of knowledge, trade links, and cultural exchanges, setting the stage for a truly cosmopolitan identity long before 1530.

Birgu: The Heart of Malta’s Early Fortifications

Known today as Vittoriosa, Birgu was the center of activity among the Three Cities. The name “Birgu” itself likely originates from the Arabic word “burg,” meaning borough, as it served as a key settlement during the Arab period. Ancient remains—including rock-cut tombs from the Phoenician period and Roman artifacts—point to a long-standing settlement in this area.

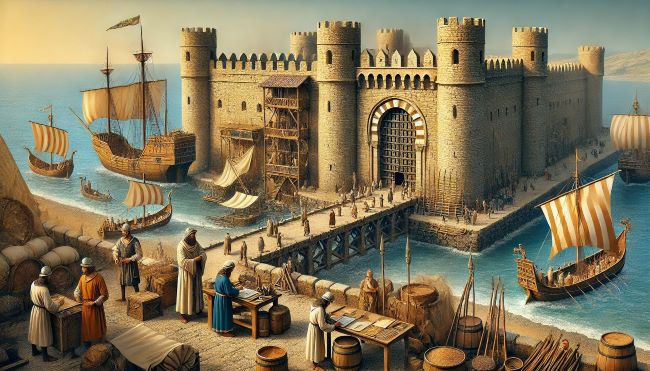

By the medieval era, Birgu had developed into a fishing village with a strong maritime identity. At its core was Castrum Maris (later renamed Fort St. Angelo), a fortress whose foundations date back to the Byzantine period. Expanded by the Arabs and later fortified by the Normans, this castle became Malta’s principal defense site by the 15th century, acting as the seat of the Castellan, a local governor who managed the island’s defenses.

At this time, Birgu’s small harbor could host a few vessels at once, and while exact shipping records are scarce, estimates based on trading documents suggest that several dozen merchant trips per year passed through this key node. Each culture contributing to its maritime soul brought subtle shifts in trade volumes and commodities—from Phoenician amphorae filled with olive oil to Roman grain shipments and Arab-introduced citrus produce. Over centuries, the fortress walls, shaped and reshaped by different rulers, helped secure these valuable exchanges.

Bormla: The Supportive Community

Situated just behind Birgu, Bormla (today known as Cospicua) grew as an essential support community, providing the resources and labor needed for daily life. The name “Bormla” may derive from the Phoenician word “Bir,” meaning “well,” hinting at the natural springs that made this area valuable. Initially an agricultural community, Bormla’s fertile land and fresh water sources were vital to the local economy, supplying food and resources to the Grand Harbour area and its inhabitants.

By the 15th century, Bormla had developed further, with a small but growing population engaged in agriculture and trade, supporting the defense efforts and daily needs of its larger neighbor, Birgu.

If we could quantify Bormla’s contribution to the local food supply, we might say that its fields produced a reliable surplus—enough to help feed hundreds of people annually, offsetting any shortages from fishing and maritime trade. A modest fraction of this produce could even be traded abroad, supporting fledgling economic networks. The “wells” referenced by the city’s name may have ensured more consistent harvest yields compared to other, drier parts of the islands.

Maltese Cotton Trader and his Donkey

Isla: The Maritime Outpost

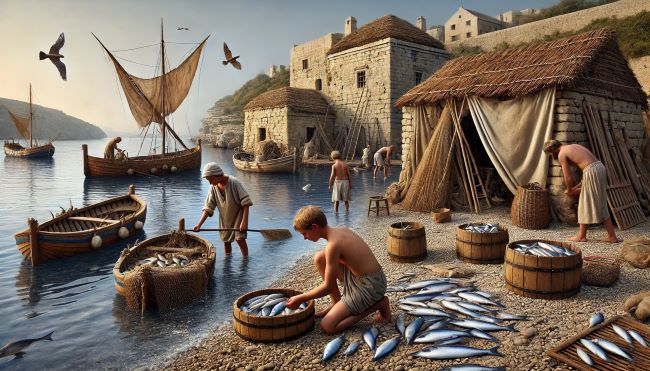

On the narrow peninsula facing the Grand Harbour, Isla (now Senglea) was primarily a fishing base with limited permanent settlement before the Knights arrived. Known as L’Isla or Isola San Giuliano, it offered an excellent vantage point over the harbor, making it ideal for monitoring maritime activity. While evidence suggests it hosted a few lookout posts, Isla was mostly inhabited by fishermen who relied on the rich waters of the harbor for their livelihood.

Archaeological estimates and historical accounts aren’t precise, but considering the harbor’s abundance, a handful of Isla’s fishermen could reliably net enough fish to feed local households multiple times over the course of the year. This steady supply of fresh catch not only satisfied local appetites but occasionally made its way into the larger trade economy, reinforcing Isla’s critical, if understated, role in regional sustenance.

Trade and Maritime Activity

The Grand Harbour has been a crucial port since Phoenician times, connecting Malta to wider Mediterranean trade routes. Birgu, with its accessible waterfront, became the primary trade center by the 15th century, with regular exchanges with Sicily and North Africa. Fishing was central to the economy, providing both food and trade goods, and a small shipbuilding industry emerged to support the growing maritime community.

By the late medieval period, the local shipbuilding and maintenance industry—though small—might have serviced a few dozen vessels each year, ensuring they remained seaworthy for trade runs between Sicily, North Africa, and beyond. While “regular exchanges” are hard to quantify precisely, surviving records hint that at least several trade voyages per season took place, allowing the exchange of goods like grain, olives, wine, salt, and textile products.

The Early Community and Social Life

While small by today’s standards, the population of the Three Cities had developed a unique social structure by the late medieval period: Birgu had around 500-700 inhabitants and served as the primary settlement. Bormla supported about 200-300 people, largely engaged in agriculture and local crafts. Isla had only a handful of permanent residents, mostly tied to fishing.

The local governance was centralized at Castrum Maris, where the Castellan managed defenses and regional affairs. Religious life focused on the Church of San Lorenzo in Birgu, a communal center where people gathered for worship and social events.

In total, these rough population estimates (ranging from a few hundred in Birgu to mere dozens in Isla) illustrate just how intimately scaled life was. Everyone counted—every fisherman’s haul, every harvest from Bormla’s fields, and every fortification upgrade in Birgu’s castle. Together, these small numbers formed the backbone of a tight-knit society where resources had to be efficiently managed and shared.

Unearthing the Past: Archaeological Discoveries

Recent excavations have shed light on the Three Cities’ rich past, revealing Phoenician-Punic tombs and other burial sites, Roman ceramics that indicate trade and daily life, and foundations of medieval buildings and Arab-period fortifications at Castrum Maris, underscoring the area’s strategic importance. These findings illustrate that, far from being a backwater, the Three Cities were thriving settlements with deep connections to the ancient Mediterranean world.

The quantity of recovered ceramics, for instance, though not easily counted in exact numbers, provides a tangible measure of past trade intensity. Each find suggests multiple transactions and exchanges, hinting that over centuries, thousands of pottery pieces passed through these communities. Every newly excavated shard adds one more data point to the region’s vibrant history.

Conclusion: A Foundation for the Knights

Before the arrival of the Knights of St. John, the Three Cities were distinct yet interconnected communities. Birgu was a bustling trade hub with its fortified castle, Bormla was a vital agricultural and support town, and Isla served as a practical fishing outpost. This foundation allowed the Knights to build upon an already well-established social and defensive network when they arrived, transforming the Three Cities into the powerful stronghold they would become.

Taken together, these statistics and estimates—whether it’s the number of inhabitants, the yearly count of vessels docking at the harbor, or the volume of agricultural and fishing yields—serve as numeric echoes of the Three Cities’ long, layered past. By better understanding the scale of their commerce, population, and resource management, (see also: self-guided water tour of Malta) we see that Malta’s Three Cities were never static footnotes in someone else’s story. They were dynamic, influential centers of exchange and life, laying the groundwork for the dramatic transformations that would come under the Knights of St. John.