DISCLAIMER

This is a work of fiction. While it incorporates historical events, all characters, conversations, and supernatural elements are fictional. Any resemblance to real persons beyond general historical context is coincidental. Historical liberties have been taken for narrative purposes. Future chapters are speculative fiction only. All rights reserved ManicMalta.com. This book cannot be reproduced in part or in full, copied or printed.

The truth about islands is this: they are never truly isolated.

The sea that surrounds them is not a barrier but a road. A road with no signposts, certainly. A road where the unwary might drown. But a road nonetheless.

After the temple builders faded, I slumbered. Not the deep unconsciousness of before, but a drowsy half-awareness. I felt the seasons change. I watched the abandoned temples weather under sun and wind. I observed the small settlements of bronze-workers who replaced my vanished people.

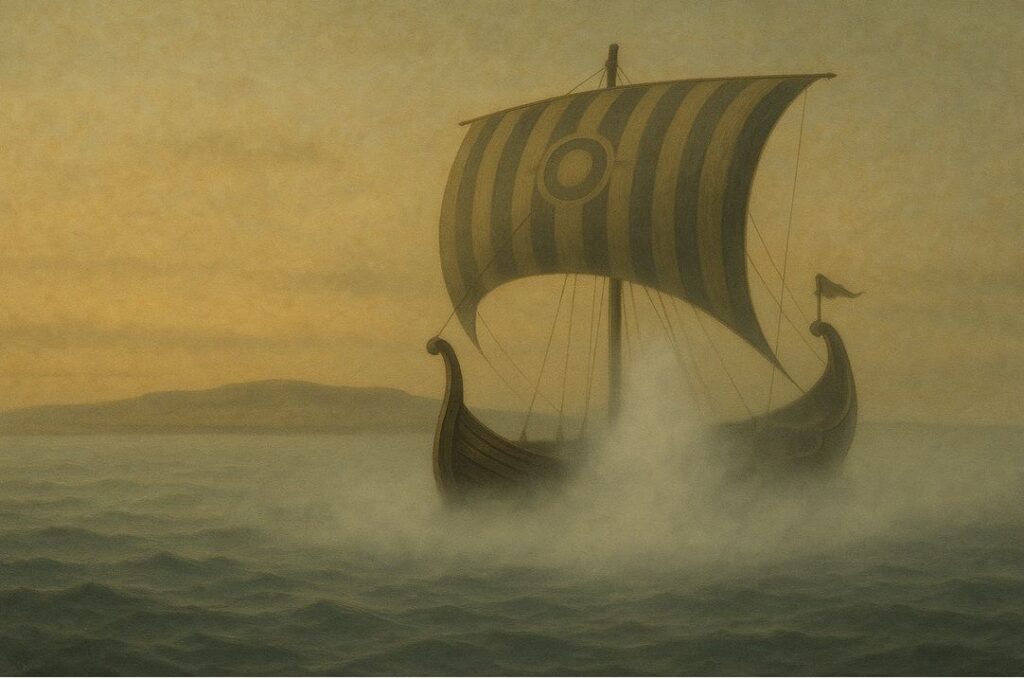

And then, from the east, I saw new sails on the horizon.

PURPLE SAILS

They came with cedar ships and curious eyes. Men with dark beards and strange syllables in their mouths. They called themselves Phoenicians, though that was not the name they used among themselves. They were traders from cities like Tyre and Sidon, on the coast of what you now call Lebanon.

It was around 800 BC when they first established permanent settlements on my shores. Before that, they had come only to trade, to shelter from storms, to replenish water. Now they built stone houses and harbors.

Their ships carried purple-dyed textiles – the royal purple made from murex snails that made them famous throughout the Mediterranean. They brought glass beads, carved ivory, and cedar wood. They took with them the meager products of my soil, but mostly they valued my harbors.

Purple cloth and timber ships Words that dance upon the tongue The world grows larger

The Phoenicians saw what my temple-builders never did: my strategic value. My two islands stood at the waist of the Mediterranean, a natural stopping point between east and west. A place to shelter, to repair ships, to trade news and goods.

And they brought me a gift beyond price.

Letters.

The Phoenicians carried with them a revolutionary idea: that the sounds of speech could be broken into component parts and represented by simple symbols. Their alphabet of twenty-two letters would eventually evolve into the very letters your eyes trace across this page.

Words, captured and preserved. Stories that could outlive their tellers. Ideas that could travel across time.

For the first time, I understood that I was not the only keeper of memories.

The Phoenicians called my larger island “Maleth” – a harbor, a haven. The name would stick, with variations, through all the centuries to come.

They built a settlement that would become the city of Mdina, on a plateau in the island’s center. From there, they could spot approaching ships from any direction while remaining protected from surprise attack.

I remember a Phoenician merchant named Hanno. Not because he was particularly important in your histories – he wasn’t – but because he was the first person since the temple priestess to sense my presence.

He was walking alone on the cliffs of what you now call Dingli. The Mediterranean sun was setting, painting the limestone gold. Hanno had sailed to Egypt and back three times, had weathered storms that shattered other vessels, had bargained with princes and peasants alike. He was wealthy now, respected, with a Maltese wife and three children who spoke both his language and hers.

He stood at the cliff edge, looking out over my western waters. The sea breeze tousled his graying beard.

“I know you’re there,” he said in Phoenician. “Spirit of this place. My wife’s grandmother told stories of you.”

I rustled the scrubby bushes around him, though there was no wind.

Hanno smiled. “My thanks for safe harbors,” he said simply. Then he walked back to his home.

Not all who come to these shores take. Some also give. Some also see.

The Phoenicians prospered here for centuries. They intermarried with the descendants of those who had come before. They built olive presses. They carved tombs into the rock. Their pottery and jewelry show that they maintained contact with their homeland even as they became distinctly Maltese.

But the Mediterranean is not just a road for merchants.

It is also a road for armies.

CHILD OF CARTHAGE

Carthage was originally just another Phoenician colony, founded on the coast of North Africa by settlers from Tyre. But it grew wealthy and powerful beyond its parent cities. By 600 BC, Carthage dominated western Mediterranean trade, and Malta fell under its influence.

The transition was gradual, not a conquest. Phoenician Malta simply became Carthaginian Malta through economic ties and political reality. The culture remained essentially Phoenician, but taxes flowed to Carthage, and Carthaginian governors occasionally intervened in local affairs.

I remember a girl named Tanit, named after the chief goddess of Carthage. She was born in Maleth in 264 BC, the very year that everything began to change.

That was the year when Rome and Carthage, the two great powers of the western Mediterranean, began their first war.

Tanit was too young to understand the news that traveled from ship to ship. Too young to comprehend why her father, a sailor on a Carthaginian trading vessel, suddenly spoke of war. Too young to know that two empires were stretching their arms across the sea, grasping for control of Sicily – and that Malta lay in the shadow of their reach.

She played in the narrow streets of Maleth, chasing chickens and singing songs to Astarte, goddess of fertility. She carried water from the cistern, helped her mother grind grain, learned to spin wool into thread.

By the time she was ten, the First Punic War had been raging for a decade. Her father had not returned from his last voyage. Ships brought less trade and more wounded men.

On a spring morning in 254 BC, Tanit climbed the city wall – strictly forbidden, but she was quick and knew when the guards changed shifts. From her perch, she could see across the fields to the distant harbor. She was the first in the city to spot the approaching fleet.

Not the curved cedar ships of Carthage. Something different. Ships with banks of oars that rose and fell like the legs of water insects. Ships with strange emblems.

Roman ships.

A girl on a wall Ships bringing change I taste iron on the wind

The Romans took Malta with little resistance. The Carthaginian garrison was small, focused mainly on maintaining order rather than repelling invasions. The local population, after centuries of Carthaginian taxation, had little interest in dying for their distant overlords.

Tanit watched from hiding as Roman soldiers marched through the gates of Maleth. She heard the clash of weapons, smelled smoke from buildings set ablaze. She ran home through back alleys to find her mother already packing their few valuables.

“Quickly,” her mother hissed, shoving a small bundle into Tanit’s arms. “We go to your uncle’s farm. The Romans will take the ports first.”

As they slipped out through a small gate on the city’s southern side, Tanit looked back at the only home she had ever known. Roman banners now flew above the walls.

I have seen this scene repeated through centuries. Invaders come. Those who can, flee. Those who cannot, adapt. The island endures. Its people endure.

ROMAN WAVES

The Romans sacked Maleth but did not destroy it. They were practical conquerors. Destroy too much, and your new possession becomes valueless.

They renamed the islands. Maleth became “Melita,” and its main city became known as “Melita” as well. They built villas with elegant mosaic floors. They constructed aqueducts and baths. They replaced the Punic gods with their own pantheon, though many Maltese continued to worship their traditional deities in private.

Tanit survived the conquest. She and her mother eventually returned to the city after the initial violence subsided. Her mother took work as a servant in a Roman household. Tanit grew up, married a local craftsman, had children of her own. She learned enough Latin to trade in the marketplace but spoke Punic at home.

Her life spanned the transition between worlds. Born under Carthage, grown under Rome. Her grandchildren would consider themselves Roman provincials with little memory of Carthaginian rule.

The two great powers fought a Second Punic War, and then a Third. Carthage was ultimately destroyed in 146 BC, its population enslaved, its buildings razed, its fields sown with salt.

Malta remained a quiet backwater of the expanding Roman Empire. Too small to resist, too useful to destroy, too distant to receive much imperial attention. The locals adapted to Roman rule, just as they had adapted to Carthage before it, just as they would adapt to every power that followed.

I observed the Romans with curiosity. They were builders, like my temple people. But they built for comfort and control, not for mystery and worship. Their structures were rational, orderly. Their minds similarly arranged.

The island prospered under Roman rule. The soil was thin, the rainfall unreliable, but Malta found other ways to generate wealth. The women were famous for their fine textiles. The harbors provided services to ships plying the maritime trade routes. The nobles in their villas lived in luxury, while the common people endured as they always had.

And then came the storm that would change everything.

THE SHIPWRECK

It was the autumn of 60 AD. A grain ship from Alexandria was attempting to reach Rome, but the late season winds were treacherous. After fourteen days of being driven across the Mediterranean, the ship was in danger of breaking apart.

Among its passengers was a prisoner being transported to Rome for trial. A tent-maker, a Roman citizen, and a follower of a new religious movement. His name was Paul.

The ship never reached Rome – not that voyage, at least. It was wrecked on the rocky northern coast of Malta, in a bay now bearing Paul’s name. According to the account later written, all 276 people aboard survived.

Timber splinters against stone A prisoner brings a message Seeds planted in storm soil

I remember the night of the shipwreck well. The rain fell in sheets. The wind howled across my landscape, bending trees and sending debris flying. The sea was a tumult of white-capped waves and deadly currents.

The ship struck a sandbar and began to break apart. Some passengers swam. Others clung to planks and pieces of the vessel. The island’s inhabitants, hearing the commotion even through the storm, came with torches to the shore.

A man named Publius, the Roman governor of the island, offered hospitality to the shipwreck survivors. Among them was Paul, cold and wet like the others, but possessing a calm certainty that drew attention.

The locals built a fire on the beach to warm the survivors. As Paul gathered brushwood to add to the flames, a viper, driven from its hiding place by the heat, fastened itself on his hand.

The Maltese watching immediately assumed the worst: “No doubt this man is a murderer. Though he has escaped the sea, Justice has not allowed him to live.”

But Paul simply shook the snake into the fire and suffered no ill effects. The onlookers, first expecting him to swell up and die, began to whisper that he might be a god.

I felt his presence as something new on my shores. Not a god, no. But a carrier of something powerful. Ideas have weight, you see. Beliefs bend the world in ways that swords and ships cannot.

Paul stayed on Malta for three months until the winter storms subsided. During that time, according to the account in what you call the Acts of the Apostles, he healed Publius’s father of fever and dysentery. This led many others to come for healing.

More importantly, he spoke of his god – not one of many, but a single deity who had taken human form, died, and returned from death. A god who promised eternal life to his followers.

The Maltese, like most in the Roman world, were accustomed to adding new gods to their pantheon. But Paul’s message was different. His god did not wish to join the pantheon. His god claimed to be the only true deity.

It was a shocking idea. Exclusive monotheism was rare in the Mediterranean world, limited primarily to the Jews. Now this Jewish follower of a crucified teacher was introducing the concept to Malta.

Not everyone believed. Not everyone converted. But seeds were planted that winter that would grow over centuries.

The storm that wrecked Paul’s ship would ripple through time. The religion he brought would eventually replace the gods of Rome. The small community of believers he left behind would grow until Malta became known as one of the most devoutly Christian places on earth.

All from a chance shipwreck. If you believe in chance.

When spring came, Paul and the other survivors departed on another Alexandrian ship that had wintered at Malta. The islanders, according to the biblical account, “honored us with many honors, and when we were about to sail, they put on board whatever we needed.”

Life on the island returned to its rhythms. The Roman Empire continued to rule. But beneath the surface, changes had begun.

EMPIRE’S END

For nearly four more centuries, Malta remained under Roman rule. The community of Christians grew slowly but steadily, meeting in private homes, then in small churches carved into the rock. Persecution came and went, depending on the emperor and the local governor’s enthusiasm for enforcement.

In the year 313, Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, granting tolerance to Christians throughout the empire. By 380, Christianity had become Rome’s official religion.

The temples of Jupiter and Juno were abandoned or converted to churches. The old gods were renamed as demons. The new faith absorbed local customs and traditions, transforming them to serve its purposes.

I watched with fascination. These Christians worshipped a god who had died, like my temple people had worshipped the cycles of life and death. They built churches atop the ruins of earlier temples, as if divinity concentrates in certain locations across generations. They spoke of resurrection, of life after death.

Perhaps I too had experienced a kind of resurrection, awakening from the slumber that followed my temple builders’ disappearance.

But the Roman Empire was failing. Barbarian invasions, economic decline, and internal corruption weakened its hold on its far-flung territories. In 395, the empire formally split into Eastern and Western halves. Malta fell under the jurisdiction of the Eastern Empire, which we now call Byzantine.

The Western Empire collapsed in 476, but the Eastern portion continued, gradually transforming from Latin-speaking Romans to Greek-speaking Byzantines. Malta became increasingly oriented toward Constantinople rather than Rome.

Byzantine rule brought Greek influence to the island’s architecture, art, and religious practices. The Maltese adapted once again, learning enough Greek to communicate with their governors while maintaining their distinctive local culture.

Empires rise and empires fall My stones remain My people endure

Life under Byzantine rule was neither particularly good nor particularly bad for the average Maltese. Imperial tax collectors came. Pirates occasionally raided the coasts. Droughts came and went. Children were born, grew old, and died, most never traveling more than a few miles from their birthplace.

And then new sails appeared on the horizon. Ships from North Africa carrying men with a new faith and a new empire.

The Arabs were coming.

And with them, yet another rebirth for my islands.

This is how it has always been. Traders and conquerors, coming and going. Each leaving something behind—a word, a custom, a building technique, a strand of DNA.

Layer upon layer, like the sedimentary rock that forms my body.

I am Il-Ħares, and I remember them all.

Author’s Note

The narrative, Traders & Conquerors: Il-Ħares: Chapter 2, is a work of fiction inspired by the historical transitions of the Maltese islands from the Phoenician period (circa 800 BC) through Carthaginian and Roman rule, to the early Christian era (circa AD 60) and the onset of Byzantine influence (AD 476). The character of Il-Ħares, the Phoenician merchant Hanno, the girl Tanit, and specific events like their interactions are imaginative creations. However, the story draws on the real historical context of Malta’s role as a Mediterranean crossroads for traders and conquerors, including the Phoenician alphabet, Roman infrastructure, and the introduction of Christianity via St. Paul’s shipwreck.

For readers interested in the factual history behind this fictional tale, the following articles from Manic Malta provide detailed insights into the historical and cultural elements that inspired this story:

- Phoenician History in Malta – Explores the Phoenician settlement, trade networks, and cultural contributions, such as the alphabet, that shaped Malta as a Mediterranean hub.

- Malta Historic Water Trail: Springs & Aqueducts – Discusses Roman aqueducts and water management systems, reflecting the infrastructure developments during Roman rule.

- Water History Malta: Ancient & Modern Solutions – Covers ancient water management, including Roman contributions, which supported Malta’s prosperity under the empire.

- A Brief History of Malta – Provides an overview of Malta’s history, encompassing the Phoenician, Carthaginian, Roman, and early Christian periods described in the narrative.

These articles provide a factual foundation for understanding the historical dynamics and cultural shifts that inspired the fictional narrative of Il-Ħares in this chapter.