The Ottoman attack on Gozo in 1551 was a devastating raid conducted by the Ottoman Empire and their North African allies, the Barbary corsairs, led by the infamous corsair Dragut (Turgut Reis) and the Ottoman commander Sinan Pasha. This attack was one of the most destructive events in Gozo’s history, resulting in the island’s near-total depopulation and serving as a precursor to the Great Siege of Malta in 1565.

Context

The Ottoman Empire, under Suleiman the Magnificent, was expanding its influence across the Mediterranean. The island of Malta, held by the Knights of St. John (or the Knights Hospitaller), stood as a strategic point in the central Mediterranean, controlling key maritime routes between Europe and North Africa. The Knights frequently raided Ottoman and North African ships, disrupting Ottoman trade and naval activities. The Ottomans, in turn, sought to weaken the Knights’ presence in Malta by attacking vulnerable parts of the Maltese archipelago, including the neighboring island of Gozo, which was less fortified than the main island.

The Attack on Gozo

In July 1551, a large Ottoman fleet, reportedly consisting of 140 ships and around 10,000 men, arrived off the coast of Malta. After an unsuccessful attempt to attack the fortified city of Mdina on Malta’s main island, the Ottoman forces turned their attention to Gozo, which was less defended and more exposed.

- Landing and Siege:

- The Ottomans landed on Gozo’s shores with little resistance. The local garrison and residents, numbering fewer than 500 defenders, retreated to Cittadella (also known as the Citadel or Castello), a small fortified complex near the center of Gozo, which served as the island’s main defensive structure.

- The Citadel was not well-equipped to withstand a prolonged siege. It had low, inadequate walls, and its supplies were limited, making it difficult for the defenders to hold out against a massive force.

- The Ottomans laid siege to the Citadel, bombarding it with artillery and quickly overwhelming the defenders.

- Surrender and Aftermath:

- After just a few days, realizing that resistance was futile, Governor Gelatian de Sessa and the remaining Gozitans surrendered to the Ottomans in hopes of mercy.

- However, instead of sparing the residents, the Ottoman forces rounded up nearly the entire population of Gozo—around 5,000 to 6,000 people—and transported them to the coast. They were forced onto ships and taken to Tripoli, in present-day Libya, which was then under Ottoman control. Interestingly at least one priest returned to Gozo after a ransom was paid.

- Enslavement and Deportation:

- The captured Gozitans, including men, women, and children, were enslaved and transported to Tripoli, where they were sold or used as laborers. Only a small number managed to escape or avoid capture by hiding in remote parts of the island.

- The event was catastrophic for Gozo, as the island was effectively depopulated and left desolate. It would take generations for the population to recover.

- Destruction of Gozo’s Infrastructure:

- Following the capture and enslavement of its population, the Ottomans and corsairs destroyed parts of Gozo’s infrastructure. They sacked villages, looted valuables, and left much of the island in ruins.

- The Citadel itself sustained damage, though it would later be repaired as part of the Knights’ renewed fortification efforts.

- Depopulation and Slow Recovery: The island of Gozo was largely deserted after the raid. The Knights of St. John and the Maltese authorities made efforts to repopulate the island, encouraging settlers from mainland Malta and Sicily, but it took decades for the population to return to pre-1551 levels.

Interesting Read: What happened to the Maltese Economy after the attack of 1565?

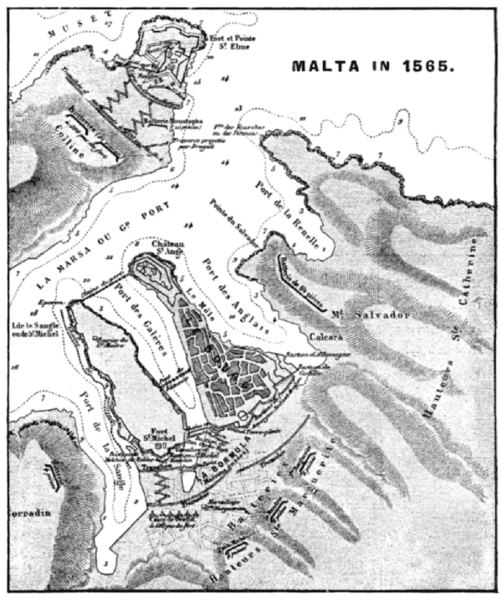

Impact : The Knights fortifying the three cities

The Ottoman attack on Gozo had far-reaching consequences, not just for Gozo but for the entire Maltese archipelago, the knights beefed up the construction of multiple Forts of Malta—Fort St. Elmo, Fort St. Angelo, Fort St Michael and Fort Ricasoli—reflects the strategic military architecture efforts by the Knights of St. John to fortify Malta against Ottoman invasions and ensure its protection as a critical Mediterranean stronghold.

Situation in 1551:

In 1551, Malta’s Grand Harbour area was still lightly fortified, especially compared to the defenses it would have in later years. This left Malta’s main settlements more vulnerable to potential attacks.

Birgu (Vittoriosa) and Senglea (Isla) in 1551

- Birgu, the primary base of the Knights of St. John, had Fort St. Angelo, the strongest fortress in Malta at the time. However, outside of Fort St. Angelo, Birgu’s defenses were not yet extensive.

- Senglea, across from Birgu, was mostly undeveloped and had almost no fortifications in 1551. Significant defenses, such as Fort St. Michael, would only be built after the Great Siege of 1565.

Bormla (Cospicua) in 1551

- Bormla (now Cospicua) was completely exposed in 1551, with no major fortifications. It would only be fortified years later with the construction of the Santa Margherita Lines in 1638 and the Cottonera Lines in the 1670s.

Malta’s Overall Defense in 1551—and the Ottoman Decision

At this time, Malta’s defenses were still relatively weak. Even the Ottomans, who attacked in 1551, chose not to strike Malta’s main settlements because they saw its defenses as too strong to overcome easily without significant loss. Instead, they turned their focus to Gozo, which was far more vulnerable. This strategic choice showed that, despite Malta’s limited defenses, Fort St. Angelo and Birgu still posed enough of a challenge to deter the Ottoman forces.

This close call revealed the island’s vulnerabilities and spurred the Knights to invest heavily in fortifications as they prepared for the Great Siege of 1565. After their defeat in Rhodes, the Knights were determined not to face the same fate again. They were well-financed through their corsair operations (see also: History of Piracy), which allowed them to fund extensive defenses. This investment fueled an arms race between defenders and attackers.

Here is an outline of the building process, the architects involved, and the timeline for each fort:

1. Fort St. Elmo (Valletta)

- Location: Positioned at the tip of the Sciberras Peninsula, guarding the entrances to both Grand Harbour and Marsamxett Harbour.

- Purpose: This fort was key in defending against invasions from the Mediterranean, especially during the Great Siege of Malta by the Ottoman Empire in 1565.

- Construction Timeline: Initial construction began in 1552. It was later expanded and fortified after the Great Siege.

- Architect: The initial design was executed by Giovanni Battista Calvi, an Italian military architect. Calvi’s plans focused on optimizing defensive capabilities to cover both harbors.

- Key Developments: Fort St. Elmo underwent significant strengthening and expansion after the Siege of 1565, during which the original structure was severely damaged. It was later reinforced and adapted to accommodate artillery advancements and provide a robust defense line.

2. Fort St. Angelo (Birgu)

- Location: Situated at the tip of the Birgu Peninsula, Fort St. Angelo served as the headquarters of the Knights of St. John and provided control over the Grand Harbour.

- Purpose: It was the Knights’ primary defensive structure, especially critical during the Siege of Malta, and played a central role in the defense of the island.

- Construction Timeline: The structure was originally built as a medieval castle (known as the Castrum Maris) and was significantly expanded and reinforced by the Knights starting around 1530.

- Architect: Fort St. Angelo’s enhancements were managed by Antonio Ferramolino, a military engineer brought in by the Order of St. John. Ferramolino’s work included upgrading the fort’s fortifications to withstand contemporary siege tactics. This fort was built on top of another older fort, Castrum Maris.

- Key Developments: Over time, the fort was modernized with the addition of bastions, and improvements continued under various Grand Masters. Its design was continually modified to counter evolving military technology, including improved artillery defenses.

St. Michael Fort, often referred to as Fort St. Michael, was one of the main defensive structures in Malta alongside Fort St. Elmo and Fort St. Angelo. Located on the Senglea Peninsula (also called Isla) across from Birgu, it was crucial in protecting the Grand Harbour during the Great Siege of Malta in 1565.

3. Fort St. Michael (Isla)

- Location: Situated on the Senglea Peninsula, guarding the southern approaches to the Grand Harbour.

- Purpose: Built by the Knights of St. John to fortify Senglea and provide a protective line along with the other two major forts (St. Elmo and St. Angelo), Fort St. Michael was key to Malta’s harbor defenses.

- Construction Timeline: The construction began in 1551 under Grand Master Juan de Homedes, spurred by an Ottoman raid that highlighted the vulnerability of Malta’s harbors.

- Architect: The main military architect for Fort St. Michael was Pedro Pardo d’Andrera, who designed it to cover the Senglea Peninsula and complement the other two forts, creating a triangular defensive layout around the Grand Harbour.

Key Historical Significance

- Role in the Great Siege of 1565: Fort St. Michael became famous for its role in the Great Siege of Malta, where it withstood intense Ottoman attacks. Despite severe bombardments and multiple assaults, the fort held, thanks to the resilience of the defenders and the strength of its design.

- Post-Siege Enhancements: After the Great Siege, Fort St. Michael was extensively repaired and upgraded. New bastions and walls were added, and it became an integral part of the extensive fortification network that the Knights continued to build across Malta.

Architectural and Military Features

- Bastions and Artillery Positions: Like other forts, Fort St. Michael was built with bastions to withstand cannon fire, and it housed heavy artillery to counter naval and land-based assaults.

- Defensive Improvements: Following the siege, the fort was strengthened with a more substantial wall circuit and integrated into the surrounding network of fortifications, making Senglea one of the best-defended peninsulas in the Grand Harbour area.

Fort St. Michael’s resilience during the siege cemented its place in Maltese history and remains a symbol of Malta’s formidable defense against overwhelming odds. Today, much of the original fort has been integrated into modern developments, though its historical significance endures. This great military engineering feat baked in the win for the Knights, they invested heavily and the investment paid off. The great Siege has a lot of similarities with the Siege of Osaka and many other Sieges.

3. Bormla (Cospicua)

Interestingly, Bormla lacked significant fortifications in 1551, and it wasn’t until 1630 that the Knights

Conclusion

These fortresses were designed to slow down the enemy, making any assault costly and creating conditions that might lead the attacker to make strategic mistakes amidst the confusion of battle—an outcome that indeed occurred.

The rush to build fortresses in Malta somewhat mirrors events in Gallipoli nearly 300 years later.

The Three Cities have a rich and colorful history; without them, Europe might not be what it is today.