Fortresses Under Siege: A Comparative Analysis of the Great Siege of Malta and the Siege of Osaka

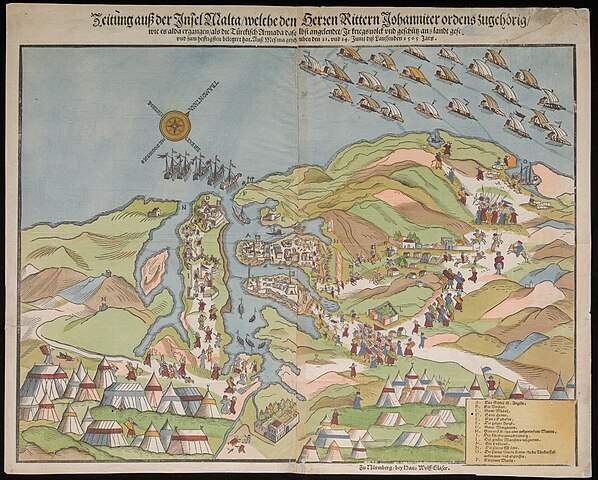

The Great Siege of Malta in 1565 represents one of history’s most iconic sieges, where determined defenders stood against overwhelming forces. In Malta, the Knights of St. John held off the might of the Ottoman Empire from fortified strongholds, including Fort St. Elmo on the Sciberras Peninsula (now Valletta), Fort St. Angelo in Birgu, and the Three Cities.

A quick primer: Where is Malta?, a brief history of Malta and Why did the Knights build the three cities? and to that question we also see the parallels with Gallipoli.

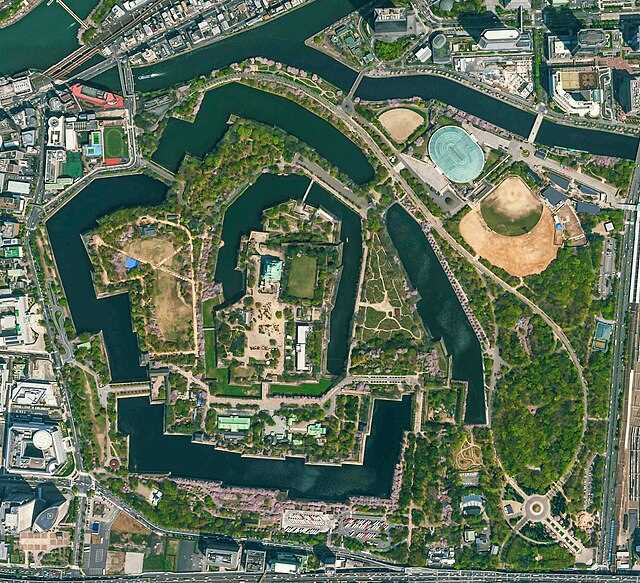

Half a world away and several decades later, the Siege of Osaka (1614–1615) unfolded in Japan, marking the end of the Sengoku period. Osaka Castle, a symbol of the Toyotomi clan’s power, became the last bastion against the unifying forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu. While separated by distance and culture, these sieges reveal how military architecture, weaponry, and tactics were shaped by regional needs. They also highlight ways in which each side might have benefited from the other’s methods. Let’s explore what the Knights could have learned from the samurai, and vice versa.

Image Credit Osaka Castle: Japan National Land Image Information

The Fortresses and Their Defenses: Context and Distinctions

Malta’s fortresses—Fort St. Elmo, Fort St. Angelo, and Fort St. Michael—were strategically placed to control access to the Grand Harbour and Marsamxett Harbour, critical to Malta’s defense. The focus on military tactics played a significant role in how these fortifications were utilized. Fort St. Elmo, situated on the Sciberras Peninsula (now Valletta), was designed to delay the Ottomans, buying time for the core defenses at Birgu and Senglea.

The fortresses featured angled bastions and star-shaped walls, optimizing for artillery defense by deflecting cannon fire and maximizing crossfire opportunities. The Knights of St. John employed overlapping fields of cannon fire and musketry to defend the harbors from multiple approaches. Notably, the Knights were skilled in both ranged and close combat, adept with swords, pikes, and firearms. Maltese civilians played a crucial role by assisting with repairs, supplying provisions, and even joining in combat, thereby strengthening the overall defense.

Osaka Castle, by contrast, stood as a towering symbol of Toyotomi power in Japan. It employed a layered moat system and massive stone walls, emphasizing both resilience and defense-in-depth. Japanese defenders relied on a combination of matchlock guns (tanegashima) and traditional samurai weapons like katanas and spears. The samurai’s approach blended gunpowder with close-combat readiness, swiftly adapting to breaches with sorties and counterattacks. Command structures were both centralized under Toyotomi Hideyori and decentralized, with individual daimyo and commanders like Sanada Yukimura responsible for specific sectors, similar to the Knights’ organization.

Lessons for the Knights of St. John from the Samurai Defenders of Osaka Castle

1. Flexible, Decentralized Defense and Night Sorties

The samurai defenders at Osaka Castle often operated under decentralized command structures, with individual leaders responsible for defending specific parts of the castle. Commanders like Sanada Yukimura led localized sorties and daring night raids, striking at Tokugawa’s siege lines, disrupting their cohesion, and wearing down their morale. These aggressive tactics forced Tokugawa’s forces to remain vigilant, expending energy and resources across their encampments.

While the Knights also employed both centralized and decentralized command, they could have further embraced such flexible tactics. Implementing more frequent night sorties and raids against Ottoman siege works might have disrupted the enemy’s plans and slowed their progress.

This decentralized model parallels the corsairing activities in Malta, where the Knights not only attacked enemy trading ships themselves but also decentralized these efforts by issuing privateering licenses to other entrepreneurial pirates or privateers . These naval wars had both strategic objectives—to slow down the Ottomans—and tactical objectives, such as supplying the Knights’ coffers to build the fortresses.

2. Layered Moat Defense and Defense-in-Depth

Osaka Castle’s layered moats were among its most effective defenses. Attackers had to cross multiple moats before reaching the inner walls, exposing them repeatedly to defenders’ fire. The layout significantly delayed attackers, giving samurai defenders the chance to target and weaken them before close combat ensued.

In Malta, Fort St. Angelo in Birgu (in Birgu), Fort St. Elmo in Valletta (in Valletta), and St. Michael in Senglea are already in a natural harbors and the sea acted as formidable barriers, but the Knights faced geographic limitations in creating additional moats. However, they could have explored the construction of artificial obstacles and trenches inland, creating a layered defense that forced Ottoman forces to overcome multiple hurdles. This concept of defense-in-depth would have bought the Knights more time to respond to breaches and possibly inflicted greater casualties on the attackers.

In addition, the Knights requisitioned all the land needed for fortifications, taking it away from the Maltese. Interestingly, Napoleon sought to dismantle these walls to weaken Malta as a fortress.

3. Integration of Traditional Weapons with Gunpowder Arms

Osaka Castle’s defenders made extensive use of matchlock guns in tandem with traditional weapons. When Tokugawa troops breached sections of the walls, samurai seamlessly transitioned to hand-to-hand combat, utilizing swords and spears. This flexibility allowed them to adapt quickly to changing battlefield conditions.

The Knights were proficient in both ranged and melee combat, but they could have further emphasized this integration within their defensive strategies. By training units specifically for rapid transition between firearms and melee weapons, they could have enhanced their ability to repel Ottoman assaults more effectively, especially during close-quarter battles following a breach.

4. Psychological Warfare and Symbolic Resistance

The samurai, bound by the Bushido code and unwavering loyalty to the Toyotomi clan, defended Osaka Castle with a profound sense of honor and duty. The castle itself was a powerful symbol, embodying the last stand against Tokugawa unification. This deep-rooted commitment boosted morale and inspired fierce resistance.

The Knights of St. John were similarly motivated by their religious mission to defend Christendom. However, they might have further capitalized on symbolic resistance by prominently displaying religious icons, banners, and emblems throughout the fortifications. Such visible symbols could have reinforced their cause, bolstering the morale of both soldiers and civilians, and sending a strong message to the Ottoman forces about their unwavering resolve.

Importantly, the Maltese side had around 1,000 slaves, while the Ottoman side relied on over 6,000 slaves, alongside a significant number of adventurers. However, the will to fight among these two groups on the Ottoman side was notably low, which likely impacted their effectiveness during the siege. This contrast highlights the challenges both sides faced in maintaining morale and cohesion among diverse groups within their forces.

Lessons for the Samurai Defenders from the Knights of St. John

1. Effective Use of Artillery and Crossfire

The Knights’ use of heavy artillery was pivotal in Malta’s defense. At Fort St. Angelo and Fort St. Michael, they strategically positioned cannons to create interlocking fields of fire that covered all approaches. Even narrow straits were guarded by overlapping cannon fire, preventing Ottoman forces from advancing easily.

At Osaka Castle, the defenders had limited access to heavy artillery due to technological and logistical constraints. However, they were not unaware of the tactical advantages of artillery. By focusing efforts on acquiring or producing more artillery pieces, even small-caliber cannons, and implementing the Knights’ crossfire tactics, the samurai could have enhanced their defensive capabilities. This would have allowed them to disrupt Tokugawa troops from greater distances and possibly hinder the construction of siege works.

2. Adapting Fortifications: The Concept of Bastioned Defense

The star-shaped designs of Maltese forts, particularly Fort St. Elmo, maximized defensive angles and minimized blind spots. The angled bastions deflected incoming cannon fire and provided vantage points for enfilading fire against attackers.

While the traditional Japanese castle design was well-suited to their warfare style, incorporating elements of bastioned fortifications could have improved Osaka Castle’s defenses against artillery. Given the limitations in technology and the cultural context, a full redesign was impractical. However, modifications such as angled walls or additional outworks might have helped deflect cannon fire and create kill zones, complicating the attackers’ advance.

3. Involving Civilians in Active Defense and Logistics

During the Great Siege of Malta, civilians were integral to the defense effort. They formed militias, assisted with fortifications, supplied provisions, and even took part in combat. This collective effort enhanced the defenders’ capacity to withstand the prolonged siege.

In Osaka, civilians did contribute to logistical support, but their involvement could have been expanded. By organizing civilian militias and involving them more directly in defensive preparations and repairs, the samurai could have bolstered their manpower. This increased participation might have enhanced morale and created a stronger sense of unity between the samurai and the common people.

4. Unified Cause and Visible Symbolism

The Knights’ defense was fueled by a powerful unifying cause—the defense of Christianity against the Ottoman Empire. This shared faith and mission unified Knights, soldiers, and civilians under a collective identity, fostering resilience and determination.

While the samurai were driven by loyalty to the Toyotomi clan, they could have amplified their cause by promoting symbols that resonated with all defenders. Emphasizing the defense of traditional Japanese values and the protection of the common people might have broadened support. Visible symbols such as banners, crests, and messages could have reinforced their stance, potentially rallying more widespread resistance against the Tokugawa forces.

Comparative Insights between the two sieges

Beyond the immediate tactics and fortifications, several other aspects offer valuable comparative insights between the two sieges.

Supply Lines and Logistics

The Knights of Malta, though besieged, managed to maintain supply lines via the sea, thanks in part to support from allied navies like that of Sicily. This external assistance was crucial in sustaining their defense over several months.

In contrast, Osaka Castle was encircled by Tokugawa forces, cutting off most external support. However, had the defenders established more covert supply lines or alliances with other regional powers resistant to Tokugawa rule, they might have extended their capacity to resist the siege.

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering

Intelligence played a significant role in both sieges. The Knights benefited from prior knowledge of Ottoman strategies and prepared accordingly. They also employed spies and scouts to gather information on enemy movements.

The defenders of Osaka could have intensified their espionage efforts to infiltrate Tokugawa ranks, gaining insights into their plans and potentially sabotaging their efforts. Enhanced intelligence could have allowed for preemptive actions against siege preparations.

Leadership and Strategic Decisions

Grand Master Jean de Valette provided decisive leadership during the Great Siege of Malta. His strategic foresight, including the reinforcement of fortifications and the rallying of troops, was instrumental in the Knights’ successful defense.

At Osaka, leadership was somewhat fragmented. While Toyotomi Hideyori was the figurehead, effective command often fell to generals like Sanada Yukimura. A more unified command structure and decisive strategic planning might have improved coordination among the defenders, maximizing their resistance efforts.

Diplomatic Efforts and External Allies

The Knights actively sought and received support from European powers, leveraging diplomatic channels to secure aid. This external support was vital in resupplying and reinforcing their positions.

The Osaka defenders could have pursued alliances with other daimyo opposed to Tokugawa rule. By uniting disparate factions under a common cause, they might have opened new fronts against Tokugawa forces, relieving pressure on Osaka Castle.

Conclusion: Cross-Cultural Military Lessons from Malta and Osaka

The sieges of Malta and Osaka Castle showcase distinct approaches to defense—one emphasizing religious duty and artillery-based fortifications, the other rooted in samurai honor and close-combat prowess. Yet, both sieges reveal tactical insights that transcend their cultures.

The Knights could have learned from the samurai’s flexibility, layered defenses, and symbolic morale, adapting to the dynamic demands of siege warfare. Conversely, the samurai defenders might have benefited from the Knights’ artillery tactics, bastioned fortifications, and civilian involvement, enhancing the depth and resilience of their defense. The knights did evolve their military tactics and prepare for more sieges after 1565.

These lessons highlight that the art of siege defense is universal, with each fortress embodying resilience and tactical ingenuity. By examining these historical events through a cross-cultural lens, we gain valuable insights into how diverse military philosophies can inspire effective, determined defense against overwhelming odds. For the Ottomans, adapting their tactics after the Great Siege also showcased the importance of learning from past conflicts.

Moreover, understanding these sieges enriches our appreciation of how leadership, unity, and adaptability can shape the outcomes of pivotal historical moments. The Knights of St. John, often described as Europe’s first pan-European organization, and the samurai defenders of Osaka Castle left legacies of courage and tenacity that continue to inspire and inform military strategy today. The evolution from corsairing tactics to broader military strategies underscores the adaptability of the Knights and their role in shaping Malta’s storied history of survival and resistance.